Authors: Finley Allott – MA Humanitarianism and Conflict Response student; Dr Jessica Hawkins – Senior Lecturer in Humanitarian Studies. Photo credits: Tapiwanashe James, Jessica Hawkins, En Xi Lim

In January 2023, seventeen postgraduate Master’s students studying at HCRI embarked on a research visit to Uganda to study the humanitarian responses to displacement. There is much that can be told about our experiences but in this blog post we focus on the role which sport can play in responding to the needs of refugees.

Prior to our visit, our teaching considered four thematic areas: the environment, gender-based sexual violence, mental health and belonging. Based on previous visits to situations of displacement in East Africa, it was these areas which are affected by and effect humanitarian response. In this post, we examine the role which sport plays on the latter two themes: mental health and belonging. It was not our intention for sport, and specifically in the case of this visit, football, to play such a dominant role in our visit but thanks to the background of the lead lecturer and a couple of students who engage with football activities at home we decided to pursue connections with a couple of groups whilst in Uganda.

Football with South Sudanese refugee team (in Kampala)

Research shows that physical activity benefits different areas of mental health, including anxiety, depression, cognitive functioning and even addiction in children and adults.[1] All of these are issues which are prevalent in a variety of refugee communities in Uganda.[2] Many have experienced loss, separation, violence and extreme poverty before, during and after being forcibly displaced from their homes. Programmes which have sport as their underlying activity, whether in a refugee or non-refugee community, profess to forge spaces of assimilation and social capital acquisition for different groups, whilst also helping refugees come to terms with and overcome their traumatic past.[3] Football, in particular, is cited as being a universal language in spaces where differences of culture and identity may exist.

Uganda is currently host to just over 1.5million refugees, mainly stemming from conflicts in the DRC, South Sudan, Burundi, Somalia and Rwanda.[4] A large proportion of these refugees are placed in the uniquely described settlements – thirteen state- and UNHCR-jointly run villages and towns where refugees are allocated land and freedom to work and move. However, some choose to leave the settlements and move to urban settings, such as Kampala which currently hosts 8% of Uganda’s refugee population.

On previous visits to refugee settlements, we were aware of how much football played a role in the day-to-day lives of refugees, for adults and children. Yet, it was apparent that many did not have the necessary kit to play safely, including any form of shoes. In advance of the trip, we reached out to the team the lead lecturer coaches Under 6s at in Manchester to enquire about donations. Word soon spread and we had over four suitcases of kit and football boots donated from AFC Urmston Meadowside, Northenden Victoria AFC, Trafford FC and others.

We engaged with two different football organisations whilst in Uganda. The first, led by Coach Jacques and the settlement commander, Mark Mutaawe, was Nakivale Soccer Academy (NSA) based in the settlement in the far south-west of the country. The settlement mainly hosts refugees from the DRC, Burundi and Rwanda.

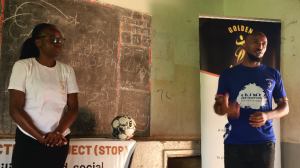

The second organisation was based in Kampala and was more formal in its set-up as an NGO, led by a former Ugandan footballer, Mo Kisirisa. Golden Boots aims to empower young people in the city through sport. It targets youth in disadvantaged communities, including young refugees. It was with the female South Sudanese refugee team that the University of Manchester group played a match against once we had learned about the organisation’s work.

Hearing from Mo Kisirisa (CEO) about Golden Boots NGO

One of Golden Boots’ key objectives is to provide the space and accessibility for young people to be physically active to overcome issues pertaining to mental health. However, aside from the actual playing of sports, the organisation has a number of concurrent activities which take place either hand-in-hand with the physical activity or through targeted outreach work in the local communities. Mental health experts are deployed to facilitate workshops and referrals to formal health services. Further, campaigns run on sensitising the target groups regarding their mental health, but also work with local communities to create cohesive relationships between refugee and host community youth. The sport improves mental wellbeing, but in addition their activities beyond that forges a safer, connected sense of belonging in Kampala for these refugees. There are also additional targeted programmes for female refugees which focus on early marriage, period poverty and tackling gender stereotypes.

Community cohesion is a key objective of the NSA. Although the teams were mostly separated by nationality, they hope that through playing against each other the children and youth could build relationships across national divides. Large tournaments are thus organised in the settlement, with the aim of promoting peace in the community through the cooperation and unity that football can cultivate. Developing talent is their second objective, as settlement commandant Mark Mutaawe spoke of how the examples of refugees making it to the top leagues of football was a source of inspiration for the Nakivale players.

There is evidence that individual physical activity as opposed to team sports has a better impact on mental health. Ley and Barrio’s review showed that yoga, tai chi and dance produced better outcomes on wellbeing with their focus on the relationship with one’s own body and psyche. [5] In contrast team sports requires communication skills between different groups. In the case of Golden Boots, presently they organise teams on mono-national lines. This can prevent conflict between different group identities but at the same time does not allow for inter-national collaboration. It was clear that the NSA was made up of different nationalities but less clear whether the teams within the academy were integrated. Yet, team sports should not be discounted as responses to mental health issues. Research shows that sports, such as football, are crucial for the social interactions recommended for sufferers of depression and PTSD.[6] The evidence on trauma-informed sport shows that “exercise, self-leadership, perseverance, structure, adult mentors, and peer interaction” are obvious consequences of engagement in football, but Berholz et al. have pointed out other significant benefits that sport can bring for an individual suffering from trauma: mindfulness, self-regulation, focus, connecting with emotions and simply just showing up.[7]

Distributing equipment at NSA (Nakivale)

Another key factor is the maintenance of sport activities. So often we hear of humanitarian and development projects lasting only as long as the funding allows. Crucially, the NSA is grassroots in its nature. Even without equipment, the playing continued. We saw one match of young boys being played with a ball of string. The settlement layout allowed for spaces where impromptu training and matches could take place in Base Camp (the central administrative zone). This is more complicated in the urban setting where space is a premium and the NGO provides the access to training grounds for its teams. As we know in British grassroots football, without the field, we cannot continue to play. The coaches are also integral to maintaining the activities; whether that is someone to organise the time and the place or a trained expert on skills, these volunteers, such as Coach Jacques and settlement commandant Mark Mutaawe, help to ensure its continuation.

Our interactions with both groups taught us a great deal about refugees and sport and how they contribute to mental wellbeing and a sense of belonging. Going forward, these organisations should continue to look at avenues to continue inclusive and trauma-sensitive sporting opportunities which involve a variety of stakeholders and target groups. Yet, they are limited by resources. Both organisations require large, collaborative grants which can provide not only the balls, nets, boots and shin pads for play, but also much needed additional support such as reusable sanitary products and experts to deliver mental health guidance. They require safe, continued use of spaces for playing and for workshops; and comprehensive training for coaches so they can recognise the trauma in individuals and when needed, provide mental-health first aid.

We are aware that encouraging sport may have its risks in refugee communities. As Ley and Barrio have pointed out, there are risks of injury for players which can cause greater issues for refugees who already struggle to access a poorly-funded healthcare system. Further, programmes which have physical activity at their core presume a basic standard of fitness for participation. There are also individuals with disabilities who cannot always be catered for and could leave to greater exclusion rather than the intended inclusionary outcomes. Yet, from our recent visit, we see that the benefits outweigh the risks.

Football has the potential to nurture a cohesive, peaceful refugee community where children and youth can forge lasting friendships across divides whilst collectively improving their mental wellbeing. Organisations like the Nakivale Soccer Academy and Golden Boots recognise this. Their efforts, as we saw on our trip, have done remarkable work in achieving this potential. Hence, if the risks can be mitigated and these efforts supported and expanded, perhaps a unique route to refugee protection- outside the traditional scope of humanitarian aid- can be discovered and advanced.

[1] Budde, H., & Wegner, M. (Eds.). (2018). The Exercise Effect on Mental Health: Neurobiological Mechanisms (1st ed.). CRC Press. https://doi-org.manchester.idm.oclc.org/10.4324/9781315113906 see also Singh B, Olds T, Curtis R, et al (2023) Effectiveness of physical activity interventions for improving depression, anxiety and distress: an overview of systematic review British Journal of Sports Medicine.

[2] Chiumento A, Rutayisire T, Sarabwe E, et al. Exploring the mental health and psychosocial problems of Congolese refugees living in refugee settings in Rwanda and Uganda: a rapid qualitative study. Conflict and health. 2020;14(1):1-77. doi:10.1186/s13031-020-00323-8.

[3] Ley, C. & Barrio, M. R. (2019) “Promoting Health of Refugees in and through Sport and Physical Activity: A Psychosocial, Trauma-Sensitive Approach” in Thomas Wenzel and Boris Drožđek, An Uncertain Safety : Integrative Health Care for the 21st Century Refugees. Cham, Switzerland: Springer.

[4] https://data.unhcr.org/en/country/uga

[5] Ley, C. & Barrio, M. R. (2019) “Promoting Health of Refugees in and through Sport and Physical Activity: A Psychosocial, Trauma-Sensitive Approach” in Thomas Wenzel and Boris Drožđek, An Uncertain Safety : Integrative Health Care for the 21st Century Refugees. Cham, Switzerland: Springer.

[6] de Assis MA, de Mello MF, Scorza FA, Cadrobbi MP, Schooedl AF, da Silva SG, et al.

Evaluation of physical activity habits in patients with posttraumatic stress disorder. Clinics.

2008;63(4):473–8

[7] Bergholz, L., Stafford, E., & D’Andrea, W. (2016). Creating Trauma-informed Sports Programming for Traumatized Youth: Core Principles for an Adjunctive Therapeutic Approach. Journal of Infant, Child, and Adolescent Psychotherapy, 15(3), 244–253.