This piece by Dr Omer Aijazi, Lecturer in Disasters and Climate Change at HCRI, was originally published in Wicked Stars: A Zin to Trouble Disaster Studies.

Fields of study are sites of inheritance. We draw upon our ancestors and elders to tell our stories. We build intellectual communities, indicate the historicity of ideas, and show who we love. But what happens if the stories we seek to tell exceed the inheritance of our fields and disciplines?

As a rite of passage, we are encouraged to understand the significance of “mapping the field” or “mapping the literature” in intellectual inquiry. But maps are restrictive, only encouraging exploration within safe bounds. They authorize a singular reality. They prevent us from getting lost. They discourage spirited wayfinding.

We are expected to learn the “canon” and then forever show mastery of authoritative texts. Given how knowledge, race, sexuality, gender, and geopolitics are co-constituted, authoritative texts often comprise of white men and white women from the Western academy, but not always. Whiteness has the privilege of being universal and normative. If we don’t cite authoritative texts sufficiently, our stories are never enough.

Elizabeth Pérez (2024) argues that citation can be a matter of life and death for Black and Latina women scholars. Citational erasure is a form of “spirit-murdering” — and scholars of color, particularly women, are killed daily (Garcia, 2020). Citational justice tells the story of erasure, how canonical knowledge reinforces existing structures of power while maintaining the status quo. Citational inertia creates partial truths and can lead to epistemic harm. What if the theoretical scaffolding provided by canonical knowledge prevents us from telling our stories? To imagine a world without Empire? To create futures that do not map onto the syntax of Western norms?

Nirmal Puwar (2020) cautions against Global North scholars who position themselves as epistemological authority over knowledge from the Global South. While such scholars seek to decenter established flows and sites of knowledge, their own center-staging, Puwar argues, reproduce the same patterns the undertaking seeks to unsettle. The author points at scholars such as Boaventura de Sousa Santos (Epistemologies of the South) and Raewyn Connell (Southern Theory). One can easily say the same about writers such as Walter Mignolo and Anibal Quijano who have established themselves as the (hegemonic) centre of decolonial thought.

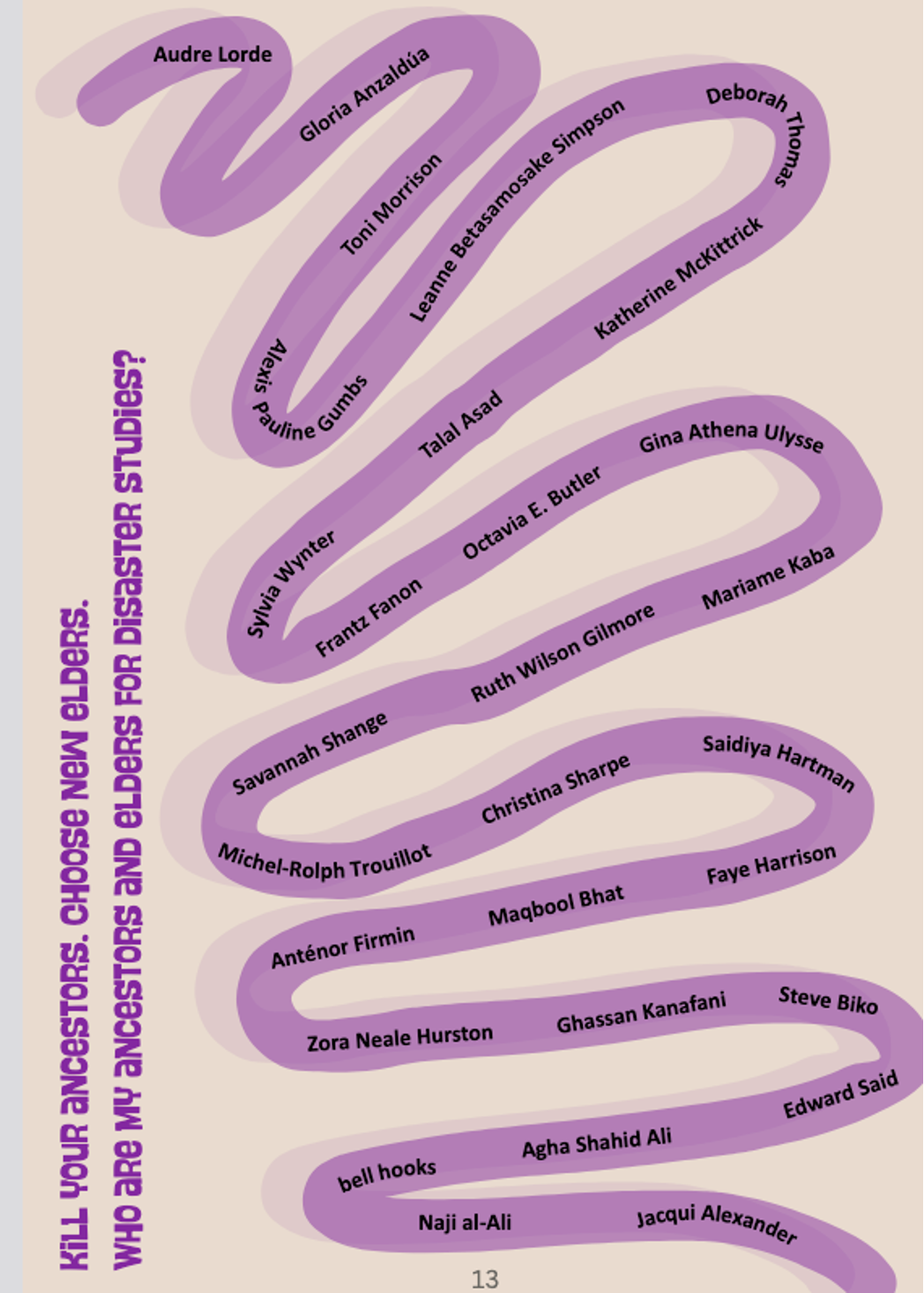

“Textual citation calls forth the names of both the living and the dead, crafting a horizontal genealogy of those with whom we share mitochondrial markers of meaning” (Shange, 2022). If we look at disaster studies, who are the people we must cite? If we scan monographs and journal articles from the field (or its many sub-areas), a familiar bibliography emerges. there is a pattern.

What will a disaster studies look like beyond Anthony Oliver Smith, Susanna Hoffman, Terry Cannon, and Gregory Bankoff? What else is there to consider besides vulnerability, risk, coping mechanisms, resilience? What if our building blocks are care, repair, reparation? What if we focus on settler-colonialism, the plantation, and carcerality? What if border abolition and NGO abolition went hand in hand with disaster recovery and social repair? What if anti-colonial, anti-fascist, anti-imperial organizing, thought, and action were placed at the heart of disaster studies?

Canonical knowledge and authoritative texts restrict us. They allow a partial image of the world, one that is steeped in power and privilege. In times of multiple genocides and ecocides, and the collapse of taken for granted (liberal) guarantees, epistemic disobedience and waywardness are warranted. Saidiya Hartman (2019) describes waywardness as “an ongoing exploration of what might be; …an improvisation with the terms of social existence, when the terms have already been dictated, when there is little room to breathe. . .the untiring practice of trying to live when you were never meant to survive” (227).

References

Garcia N.M. (2020) Spirit murdering in academia. Diverse Issues in Higher Education 26 February https://www.diverseeducation.com/opinion/article/15106340/spirit-murdering-in-academia

Hartman S. (2019) Wayward lives and beautiful experiments. W.W. Norton, New York

Pérez E. (2024) Sorry cites: the (necro) politics of citation in the nthropology of religion. Studies in Religion/Sciences Religieuses 53(2): 185-206

Puwar N. (2020) Puzzlement of a déjà vu: illuminaries of the global South. The Sociological Review 68(3): 540-556

Shange S. (2022) Citation as ceremony:#SayHerName,# CiteBlackWomen, and the practice of reparative enunciation. Cultural Anthropology 37(2): 191-198.