The booming cuisine: The irony behind innovations in the Peruvian food industry

Author: Gianna Pinasco

Peru has been named top culinary destination in the world for five consecutive years, with its booming cuisine receiving worldwide attention for its richness in flavours, diversity in spices, and notorious ingredients grown only within its territory.

The rise of globalization in the early 2000s fostered innovations in supply chain channels and acquisitions of agricultural technology, which led to increased accessibility and marketability of the country’s food industry. Citizens argue these innovations intensified social disparities, political instabilities, and environmental issues as food affordability and availability took a major hit.

In this blog I will touch upon the implications and complexities in the adoption of innovations in an agricultural industry governed by large corporations and market de-regulations. I will explore the circumstance and measures that allowed for social unrest and environmental damage in what seemed like a prosperous and fruitful food industry.

The rise of the Peruvian food industry

In the early 1990s, driven by internal political changes, Peru started investing heavily in its supply chain management, seeking to capitalize on opportunities in international markets. The innovations aimed at increasing access to ports via the amplification of Peru’s main port in Callao to facilitate the moving of products in and out of the country. Foreign investors focused on building and connecting the country via bridges, tunnels, and roads to a certain extent. Both government and private firms brought in technologies from abroad to enhance food life shelter and land efficiencies. In cities like Piura, Ica, and Arequipa, technological innovations to improve land management, automated irrigation processes, data collection sensors and drones brought greater efficiencies and profits to a handful powerful players in the industry.

The current situation is in fact problematic: foreign investors and private firms have the government tied up on long-term contracts, charging premiums and exuberant interest rates for the development of supply chain channels. Nevertheless, these investments and improvements in supply chain channels also brought money into the country. They allowed for policies in the agricultural sector to dramatically shift from a highly subsidized system in the 1980s, towards a free-market system by 2000, where the government lowered trade barriers, eliminated subsidies for locals and made access to credit harder. To expand its international alliances, the Peruvian government also signed Free Trade Agreements (FTA) with the U.S. & the EU, promoting the free trade of agricultural produce and hence strengthening relationships between the countries. A similar agreement was signed with Australia to boost commerce and ease commercial links between them. Although these measures boosted agricultural exports from $645 million in 2000 to $7.8 billion in 2020, they came at the expense of locals’ economic and social welfare.

The forgotten locals

The recent boom in agricultural industries driven by technological innovations and international partnerships, has left locals behind who are raising concern about food scarcity and increasing prices of exported products. In a country where malnutrition hits 38% of children in underprivileged areas and anemia hits 59% of children under the age of 1, food accessibility and stability is of main concern. Somehow, it seems as if the government has failed to both regulate the market and protect the most vulnerable.

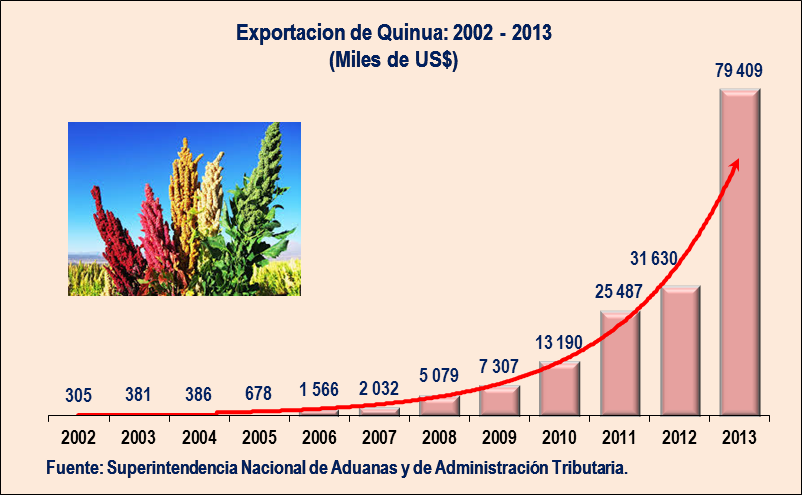

Fig 1. Rise of quinoa exports between 2002-2013 (Thousands of US$) (Source: INEI)

Quinoa, for example, used to be one of the cheapest and most abundant foods in supermarkets. In 2013, foreign researchers uncovered hidden quinoa benefits, calling it the next “superfood”. International demand for the product rapidly increased and local prices skyrocketed that same year by 158%. With technology and resources in hand, large corporations were able to build the infrastructure necessary for harvesting activities, whereas local producers could not. Not only are independent businesses unable to compete, but Peruvians are forced to pay higher prices given the limited supply left. Contrary to popular belief, it is common to find Peruvian products to be more affordable in international supermarkets. For instance, blueberries in Walmart (U.S. based supermarket) cost on average USD5/kg, while costing USD9.95/kg in Peru. With most blueberries being exported, niche markets capitalize on such opportunity by selling the limited supply at higher prices.

It is also important to highlight Peru’s inability to establish control within its borders. It is very common to see politicians end up in prison after accepting bribes to favour their own agendas (fun fact, all former Presidents are currently in jail). The instability of the country’s government and market deregulation paved the way for private institutions with proprietary innovations to enter the market. These companies’ networks include lawmakers, politicians, bankers, and leaders in the industry. Inevitably, these can capitalize on their network, technologies, and market de-regulations to gain a competitive advantage over smaller players.

In a country where economic and social disparity already create enough tension, innovation in the agricultural sector has furthered social crisis. Agriculture-dependant families are struggling to make a living out of their produce as they cannot compete with large corporations’ technologies. It is estimated that in the region of Puno, 80% of local production is still carried out by manual labour. In addition, many don’t even have access to roads or established transport system. How are independent producers, using primitive equipment, expected to compete with corporations using automated irrigation systems, and established supply chain channels?

Source: NY Times

Locals, employed by large corporations, fear increased layoffs as automation takes over their jobs. Let’s not forget that the agricultural sector employs around 20-25% of the country’s workforce. The government has tried to support workers by enforcing the new Agrarian Law, promising to increase wages by 30%. As predicted, this measure did not sit well with corporations, incentivising a hire freeze. There have been sporadic efforts from the government to provide technologies and training to independent farmers to support their small-scale businesses. But these efforts are too infrequent and lack the capacity to have a real impact for those in desperate needs. Furthermore, increased pressures on the country’s resources have led to the shrinkage of land, deterioration of soil and deforestation, driven by large corporations and illegal farmers. Eco-friendly movements are just now beginning to take a stand with demands for changes in policies and governmental bodies.

What’s next?

Clearly, the government has given large corporations too much room to do as they please. Before opening its markets, the country depended on its own people to produce food where locals benefited from different varieties of fresh food supplies at affordable prices. It is no wonder that social conflicts have intensified in a country run by large corporations and an unstable government. We can’t argue that technological innovations in the agricultural industry adopted by large firms haven’t had a positive impact on the country’s economy, because they have. But we can argue that the de-regulation in the use of technological innovations in the production of foods have led to massive social and environmental issues. It is time for a change in the governing body. The country demands access to innovations and supply chain channels to reach even the most remote places to finally put an end to malnutrition. As it turns out, getting recognition and attention for the country’s cuisine in the first place, might not have been a good thing after all.

Gianna Pinasco is a postgraduate student at Alliance Manchester Business School pursing an MSc Innovation Management & Entrepreneurship. Strong interest in sustainable innovation and start-up ventures.

An earlier version of this blog was prepared for BMAN61001 Entrepreneurship, Technology and Society, Alliance Manchester Business School, The University of Manchester.

Feature image source: Rainforest Cruises

0 Comments