Collecting, Studying, Controlling Animals in East Asia

International Workshop

The John Rylands Library and Research Institute

150 Deansgate, Manchester M3 3EH

12 June 2025

Organiser:

Dr Amelia Bonea, in collaboration with the John Rylands Research Institute and Manchester China Institute

Join us for an exciting international workshop that explores recent and deep animal histories in East Asia, at their intersections with state power, imperialism, museum practice and gender.

Attendance is free. All welcome. Please register here.

Speakers:

Dr Jaehwan Hyun (Associate Professor in the History of Science, Pusan National University)

Japanese Collectors in Colonial Korea and Memories of Imperial Natural History

This talk examines the collecting work in colonial Korea of the two Japanese naturalists, Mori Tamezō (森為三, 1884-1962) and Orii Hyōjirō (折居彪二郎, 1883-1970) and their influence on the social memories of imperial natural history in post-colonial South Korea and post-imperial Japan. In her recent book, Japan’s Empire of Birds, Japanese historian Annika A. Culver argues that both collectors were devoted local collaborators who conducted fieldwork in colonial Korea and other Japanese territories on behalf of prominent zoologists and ornithologists in Japan, such as Kuroda Nagamichi (黒田長礼,1889-1978) and Yamashina Yoshimaro (山階芳麿, 1900-1989). Their work contributed to what can be termed ‘avian (and mammal) imperialism,’ as they helped catalog the fauna in Japanese colonies, thereby scientifically asserting sovereignty over these regions.

Despite their shared role as local collaborators of avian and mammal imperialism, Mori and Orii had markedly different approaches to their collection activities in colonial Korea due to their differing positionalities. Mori settled in colonial Korea and advanced his academic career as a Japanese settler scholar, contributing to the colonial government and the colonial academia. In contrast, Orii was a freelance collector who moved between Japanese colonies, responding to the requests of his prestigious collaborators. While Mori sought the ‘uniqueness’ of Korean fauna compared to similar species in Japan proper, Orii framed Korean fauna within the broader imperial ecologies. These differences led to distinct narratives and varying degrees of recognition for these figures, as well as differing memories of imperial natural history in South Korea and Japan after World War II.

In South Korea, Mori was viewed as a Japanese scholar who was closer to ‘Korean natural history,’ in contrast to what is seen as the ‘imperial botany’ of Tokyo Imperial University’s botany professor Nakai Takenoshin (中井猛之進, 1882-1952). Meanwhile, Orii has largely been forgotten in discussions of Korean or imperial natural history in South Korea. In Japan, Mori was remembered as one of the ‘scientific Koreanologists’ rather than a contributor to imperial natural history, while Orii was represented as a prime example of the (apolitical) transnationality of imperial natural history in the first half of the twentieth century. This case study ultimately seeks to interrogate the possibility of historicizing scientific imperialism, rather than merely using it as an analytical tool.

Dr Amelia Bonea (Lecturer in Global History of Science, Technology and Medicine, CHSTM, University of Manchester)

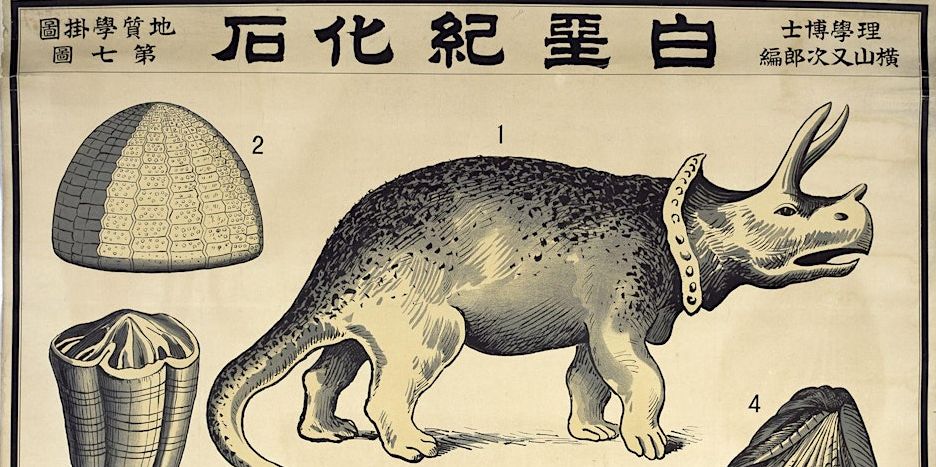

Fossil Animals and Imperial Histories in East and South Asia, 1850s-1940s

Nineteenth- and twentieth-century scientific exchanges between Japan and South Asia have attracted only a limited degree of scholarly attention, in contrast to cultural, political and economic interactions. This paper uses the example of animal fossils to discuss Japanese scientific interest in the geology and fauna of the Indian subcontinent and consider how such research was connected to investigations of extinct prehistoric fauna in the Japanese archipelago. I will argue that Japanese interest in the fauna of the Indian subcontinent was mediated, in a first instance, by the specific circumstances of British imperialism in South Asia. The discovery and subsequent study, from the early nineteenth century onwards, of sizeable collections of mammalian fossils in the Siwalik Hills of the Outer Himalayas rendered the South Asian fossil record relevant to scientific investigations on prehistoric fauna in Japan, prompting reflections on the Earth’s interconnected geological processes. South Asian fossils became important for purposes of comparison and correlation, especially after fossil remains of prehistoric elephants were unearthed in the Japanese archipelago from the mid-nineteenth century onwards. Furthermore, Himalayan fossils circulated globally, often as casts sold by British, German and French dealers who tapped into imperial networks to ply their trade in natural history specimens.

The second part of the talk will therefore discuss the acquisition routes and scientific relevance of the small collection of South Asian fossils in The Tohoku University Museum. I will show how these specimens, purchased shortly after the establishment of the Department of Geology in 1911, were important to the work of palaeontologist Matsumoto Hikoshichirō (松本彦七郎, 1887-1975), one of several Japanese scientists who made significant contributions to the study of elephants in the first half of the twentieth century. Matsumoto’s study of South Asian fossils was located at the intersections of two empires: the British and the Japanese. Indeed, he incorporated the South Asian specimens into a broader study of fossil mammals from Sichuan, which had been collected by geologist Sakawa Eijirō (佐川栄次郎, 1873-1941) and presented to the Zoological Institute of the Tokyo Imperial University. I will conclude by showing how Siwalik fossils became a tool for some Japanese palaeontologists to criticize British imperialism in Asia in the charged geopolitical climate of WWII.

Dr Hsiao-pei Yen (Assistant Professor, Institute of Science, Technology and Society, National Yang-Ming Chiao-Tung University)

Fossils, Gender, and the Nation: Mee-mann Chang and Paleontology of Early Vertebrates in Socialist China

Palaeoichthyologist Mee-mann Chang is the first and only palaeontologist to receive the L’Oréal-UNESCO for Women in Science Award, the highest honour for women scientists. Her research on fossil fish has illuminated the evolutionary adaptation of aquatic vertebrates to land. In a field historically dominated by men, where sexism and the demands of heavy fieldwork often discourage women from becoming fossil hunters, Chang’s success stands out. What does her achievement reveal about the development of palaeontology in China? Chang entered the field in the 1950s, a time when geoscientific work was promoted as one of the most promising careers for the communist youth aiming at exploring China’s natural resources for economic development. During the Maoist era, women’s commitment to palaeontology and fieldwork was further encouraged by the state’s promotion of gender equality and the glorification of chiku (enduring hardship).

This paper focuses on Chang’s personal journey to becoming a palaeoichthyologist in socialist China. Using a feminist methodology that emphasizes women’s situated agency, I primarily rely on Chang’s own recollections to reconstruct her experiences. This approach avoids the dichotomy of viewing women in socialist regimes as either victims of state-feminism or liberated individuals with absolute autonomy. Instead, I seek to understand how Chang navigated a period of political upheaval, found her niche in palaeoichthyology, and how her success, along with the broader achievements of Chinese palaeontology, was deeply intertwined with the relationship between the scientist and the state. Ultimately, this presentation explores the intersection of nationalism and gender ideology, examining how these forces converged in discovering China’s deep geo-history.

Dr Meng Zhang (Wellcome Trust Research Fellow, CHSTM, University of Manchester)

Masking Canines in China: Rabies Control, Moral Anxieties, and Blurred Human-Animal Boundaries, 1900s-50s

From the late nineteenth century onwards, influenced by bacteriological theories of rabies, both colonial and national authorities in China implemented widespread measures to control stray and domestic dogs, including the use of muzzles, registration systems, and mass vaccination campaigns. Unmuzzled dogs faced severe consequences: their owners could be fined, and the animals were often subject to execution by the police. Notably, Chinese authorities used the term kouzhao—commonly understood as ‘medical masks’ used by humans—to refer to these canine muzzles. This deliberate choice of terminology created a widespread hatred towards masks, as kouzhao were also being specifically enforced on coolies and other lower-class populations during epidemics at that time.

My presentation will explore how these public health interventions, influenced by colonial and national agendas, attempted to shift the perception of dogs from loyal protectors, traditionally allowed to bark and bite intruders, to dangerous disease carriers. I argue that using kouzhao blurred the customary Chinese distinctions between animals and humans, violating cultural norms that animals should not use the same equipment as people. This further heightened moral anxieties, particularly among marginalized groups, who saw these epidemic control measures as oppressive. This linguistic and symbolic conflation of muzzled dogs and masked humans revealed deeper tensions surrounding state authority, public health, and the marginalization of both animals and people during this period.

Moderator: Dr Aya Homei (Reader in Japanese Studies, University of Manchester)

Attendance is free. All welcome. Please register here.

0 Comments