The French Embassy to Kyiv in 1049

by mftssfs2 | Jun 11, 2019 | Uncategorised | 0 comments

The French Embassy to Kyiv in 1049 for the hand of Anna Yaroslavna, wife of King Henry I of France (d. 1060), in its Manuscript Context

Dr Talia Zajac

In spring of 1048, two French bishops and their retinue set out to travel 2,000 kilometers across Europe at the head of a delegation sent on behalf of King Henry I of France (d. 1060). They were seeking a wife for their king from the land of Rus’ (the medieval ancestor state of Belarus’, Ukraine, and Russia). My current research concerns the manuscript circulation of the note resulting from this embassy, which records the cultural and religious encounter between Latin Christian French clerics and the Orthodox Rus’.

My interest in this text forms part of a larger book project with the working title, ‘Gendering the Schism: Women’s Experiences of Religious Differences in the Orthodox-Latin Christian Marriages of Early Rus’, ca. 1000–1250’. While theological and liturgical differences between eastern and western forms of Christianity were emerging in the eleventh to thirteenth centuries, the Orthodox dynasty which ruled early Rus’ nonetheless continued to intermarry with Latin Christian rulers. Despite the fact that some sixty-two such mixed marriages took place from the eleventh to the thirteenth century, the roles of royal brides as political actors, religious patrons, and cultural bridge-builders between the ruling clan of Rus’ and Latin Christian rulers across Europe remains little known in English-language scholarship. My project aims to answer such questions as: what religious institutions did these brides support following their respective marriages? How were they commemorated as patrons and rulers in narrative and visual sources? What role did the developing Church Schism play in their reception and rule at their husbands’ courts? What role did they have in exchanging and circulating material objects, books, ideas, and religio-cultural practices between courts, and, in doing so, contributing to the creation of a cosmopolitan elite culture?

Though raised in an Orthodox environment, Rus’ princesses, like Henry I’s wife Anna Yaroslavna (d. around 1075–79), travelled across confessional and geographical boundaries to become queens consort and noblewomen ruling over Latin Christian subjects. Similarly, Latin Christian brides also travelled east to become the brides of Rus’ princes. One such bride, for instance, was the German noblewoman Oda of Stade (d. after 1076), who married Anna’s brother, Sviatoslav Yaroslavich (d. 1076). Indeed, it may have been through Oda that Henry first heard of Anna and began to consider her for a potential wife: Oda was the niece of Henry’s previous wife, Matilda of Frisia (d. 1044).

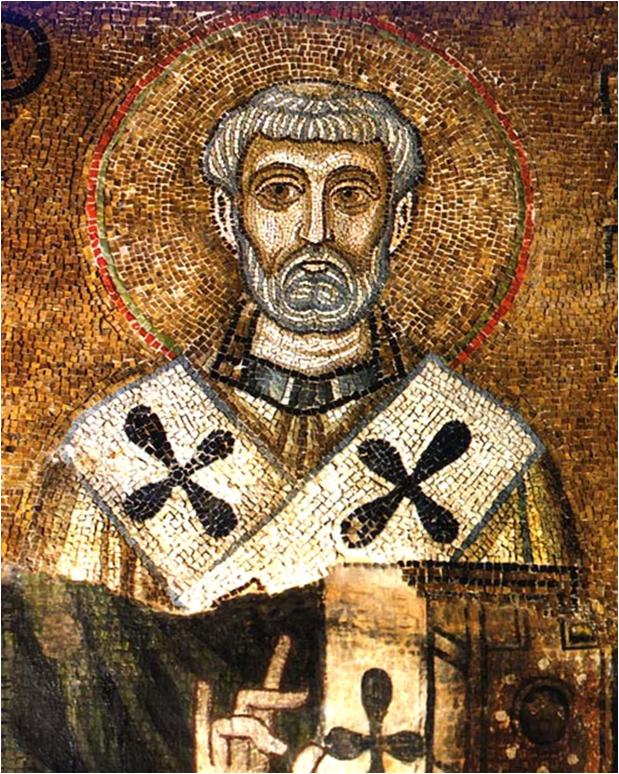

We know about the embassy sent by Henry to Kyiv to ask for Anna’s hand in marriage in 1049 firstly from a long note inscribed in the so-called Odalric’s Psalter (‘Psautier d’Odalric’, Bibliothèque municipale Carnegie de Reims, Ms. 15, fol. 214v [henceforth Reims MS 15]), named after the eponymous provost of Reims Cathedral (d. 1075/1076) who donated this manuscript to the Cathedral. This embassy account contains several features, strange to modern eyes, that pose questions about the audience and purpose of this text. Rather than describing the sights of Kyiv in 1049, the embassy account focuses instead on the legend of Pope St Clement of Rome (d. c. 100), whose relics the members of the French embassy saw during their visit to the Rus’ metropolis. According to the narrative in this manuscript, Reims MS 15, St Clement’s relics were originally discovered in Crimea by Pope Julius (d. 352) before being brought to Kyiv. This attribution of the discovery of the relics to Pope Julius is highly unusual: in all other legends (Latin, Greek, and Slavic) of St Clement, their discovery is usually attributed to St Constantine-Cyril (d. 869), who together with his brother Methodius, preached Christianity to the Slavs.

The account of the French embassy to Kyiv therefore illustrates the highly selective nature of the cultural contacts that took place as a result of Anna’s marriage to Henry. The unusual emphasis on Julius rather than Constantine-Cyril in the text is telling of the way in which stories connected with Anna’s Orthodox Byzantine origins were adapted for the needs of local French clergy in her adopted homeland.

On the basis of a comparative reading of the contents of Reims MS 15, my working theory is that the importance of Pope Julius in the story of the embassy reflects the intended audience of Odalric’s Psalter—the canons of Reims Cathedral—and that the description of the French embassy was consciously added to the manuscript to reflect their interest in church reform. Other texts included in the manuscript all emphasise papal over episcopal power and were written in the 1070s–1080 at a time when the canons sought help from the pope to depose their own Archbishop, Manassès I (r. 1069–80). The holy Popes Clement and Julius in the frame-story of the French embassy to Kyiv may have been invoked in the manuscript as saintly authorities whose authoritative writings support the canons’ reform program, including their desire to regulate the election of a bishop. Indeed, previous commentators have ignored the fact that both Clement and Julius appear elsewhere in the manuscript in texts of canon law (fol. 3r–3v), precisely as authorities on bishop’s elections.

In order to test this theory, I am in the process of hunting down six later manuscripts that I have found to date that also transmit the story of the discovery of the relics of Clement by Pope Julius. Of these, three include the frame-story of the French bishops’ arrival in Kyiv in 1049 and their viewing of Clement’s relics there. I aim to determine the contexts in which the embassy tale was read and by whom. These six manuscripts are:

1) Rome, Biblioteca Casanatense, cod. 1055

2) Charleville-Mézières, Bibliothèque municipale, MS 254 III

3) Wolfenbüttel, Herzog August Bibliothek, Codices Gudiani latini 212

4) Cambrai, Bibliothèque municipale, MS 822 (Anc. 727)

5) Saint-Omer, Bibliothèque municipale, MS 715

6) Cambridge, Corpus Christi College, Parker Library MS. 9

All originate around northern France except for Parker Library MS. 9, which comes from Worcester Priory. Of these six manuscripts, all are hagiographical collections except for Herzog August Bibliothek, 212 Gud., which includes the story of St Clement’s translation by Pope Julius within a compendium of canon law. The Cambrai, Cambridge, and Wolfenbüttel manuscripts also include the story of the French embassy’s arrival in Rus’ as a framing narrative for the relics, but the relationship between these manuscripts to each other and to Reims, MS 15 as well as the purpose of the embassy tale in them is unclear, and still need to be determined.

The subsequent marriage of Anna Yaroslavna (known in French historiography as Anne de Kyiv) to King Henri I in 1051 has long intrigued researchers, yet the way in which Anna’s medieval contemporaries understood and interpreted France’s marriage link with Rus’ has received little scholarly attention. Stefan Albrecht (2010), for instance, notes that around the time of Anna’s arrival in France, the cathedrals of Châlons-sur-Marne, Verdun, and Orléans all began to claim bishops consecrated by St Clement as their founders (Memmius, Sanctinus, and Evortius, respectively). Could Anna even have brought relics of St Clement with her to France as part of her dowry?

My work on the way the French embassy to Kyiv for Anna Yaroslavna’s hand was understood, remembered, and transmitted in Latin manuscripts is but one step toward a greater understanding of the religious and cultural consequences that followed the marriages of the ruling clan of Rus’ with their Western European medieval counterparts.

Figures:

1. St. Clement of Rome, mosaic in St Sophia Cathedral, Kyiv, 11th century. Public Domain Image.

2. Twentieth-Century Statue of Anna Yaroslavna in her foundation of Saint-Vincent de Senlis. Photograph by Talia Zajac.

Contact Us

+44 (0) 161 306 6000

0 Comments