Funding for PhDs: Shaping the Future of Science and Innovation

In this post Emily Johnson, research intern at MIOIR and final year MEnvSci Environmental Science, presents the findings of a Learning Through Research Internship. Drawing on data collected as part of the UK DGCI project funded by IRC she explores how funding for PhD training may impact UK science and innovation.

PhD research makes substantial economic, social, and cultural contributions, serving as an important channel of knowledge transfer from universities into industry and wider society. There is a growing pressure from funders, policymakers and universities that research should drive new ideas and technologies. However, the allocation of funding within the UK, incl. for PhD training, can shape research outputs and prioritise certain domains more than others. Funding has also shown to boost academic careers, and in doing so risks reinforcing existing inequalities across the science domain.

In this blog, I explore how doctoral funding from the UKRI supported doctoral students in the UK who graduated between 2019 and 2023. By combining two publicly available sources – the studentships dataset from UKRI’s Gateway to Research and the EThOS thesis archive, I identified theses that successfully secured funding and analysed whether any biases – across subject, gender or region – emerge within the funding landscape and if so, whether these trends change over time. In doing so, I also ask what these patterns mean for the future of UK doctoral research and the career trajectories of PhD students. Does the allocation of funding accelerate some research careers while limiting others, and could current practices risk reinforcing long-term inequalities?

Building the Dataset

To identify UK PhD projects that had received funding, and understand how this funding is distributed within the UK, I combined information from two publicly available datasets: 1) UKRI Studentships data: records of funded PhD projects supported by several funding bodies and 2) The EThOS thesis repository (focussing on theses completed between 2019-2023): the British Libraries online service documenting doctoral theses from UK universities.

The main challenge was linking all possible matches across the two sources. Small inconsistencies and poor formatting, such as spelling variations, the use of initials or mismatched institutions meant that identifying exact matches was often difficult. Our matching process began by cleaning and standardising both datasets before applying fuzzy matching techniques in R Studio. Uncertain cases were checked manually, and additional rounds of matching were carried out on unmatched subsets, including checks based on thesis titles and initial-based names.

Through this multi-stage process, I identified over 1,200 funded projects from the EThOS archive that had received UKRI funding. While not every project could be matched with complete certainty, the result was a strong dataset that could be analysed further. This approach allowed me to refine the matching strategy and identify false negatives within the unmatched records.

STEM Dominance in PhD Funding

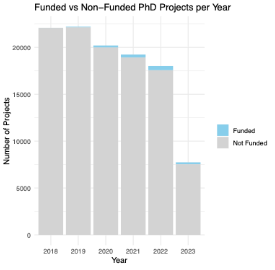

Figure 1 – Number of Funded versus Non-funded PhD Graduates per Year. Source: Analysis of EthOS and UKRI metadata.

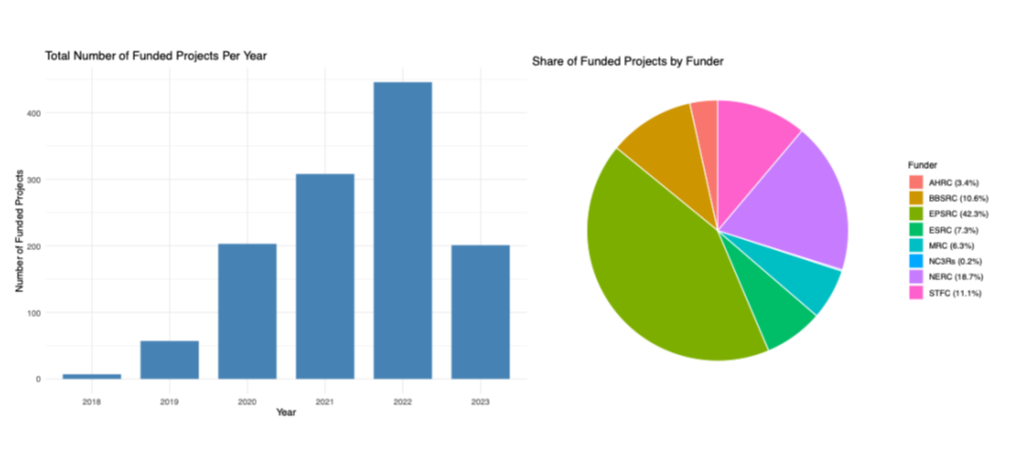

Figure 2 – The Total Number of Funded Theses per Year within the UK and the Share of Funded Theses by Funder. Source: Analysis of EthOS and UKRI metadata.

EThOS dissertation data presented a peak in PhD submissions in 2019, with over 22,000 PhD theses recorded (see Figure 1). From 2020 onwards, the total number of PhD completions shows a gradual decline, falling to approximately 18,000 by 2022 (with 2023 data being incomplete). This downward trend coincides with increasing financial pressures across the UK higher education sector. University leaders have warned of ‘catastrophic’ cuts to the sector noting that only 44% of the cost of research degrees are covered by tuition fees and sponsorship. As a result, universities are increasingly reliant on international students and external income sources to sustain doctoral provision.

This is reflected in Figure 2, where the 1,200 funded projects successfully identified and matched between 2019 and 2023, represent only around 1% of all theses recorded in EThOS during this period. The number of funded dissertations still rises steadily year on year during this period, reaching a peak in 2022 with more than 400 matches, and accounts for an increasing share of overall dissertations.

Furthermore, the distribution of funders is dominated by few research councils, such as the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC) which accounted for the largest share of funded projects, followed by the Natural Environment Research Council (NERC) and the Science and Technology Facilities Council (STFC), indicating that UKRI funding for PhD projects is highly concentrated within a few major research councils.

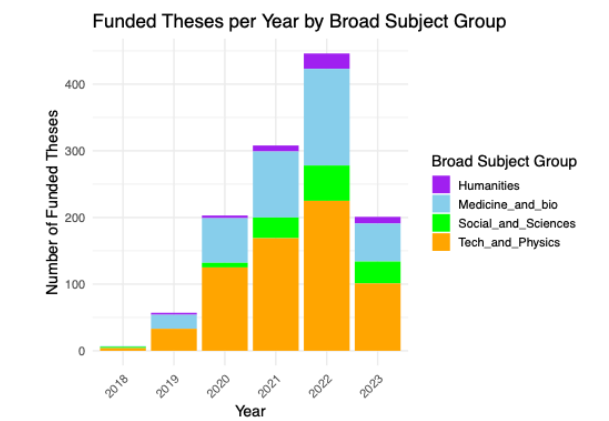

Figure 3 – Funded Theses per Year by Broad Subject Group. Source: Analysis of EthOS and UKRI metadata

The distribution of funded PhDs across disciplines highlights a clear dominance of Technology and Physics, which consistently funds the highest number of PhD projects (Figure 3). These subjects alone and combined with Medicine and Biology accounted for more than half of all funded PhDs in all years, reflecting the strong preference given towards STEMM research within the UK’s doctoral funding landscape. By contrast, Humanities and Social Sciences rarely exceeded 10% of funding combined across the six-year period, underscoring the disparity between successful STEMM and non-STEMM funded projects. The relative proportions of all subjects remained stable over time, suggesting that despite the decrease in 2023, the disciplinary balance of funding has not fundamentally changed.

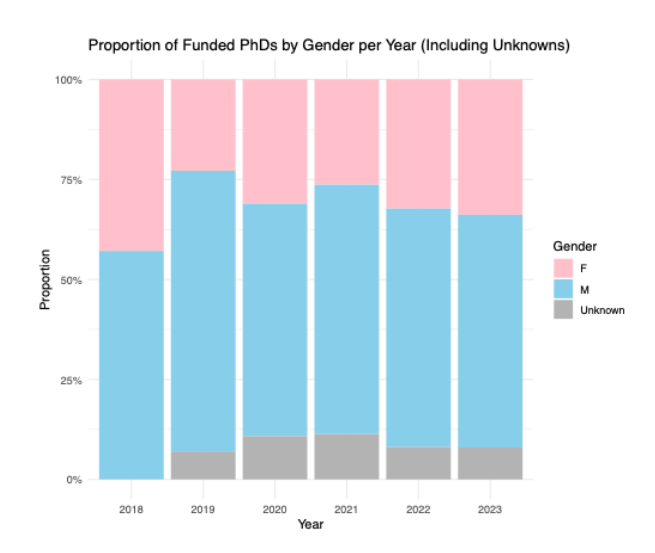

Figure 4 – The Proportion of Funded PhD Graduates by Gender per Year. Source: Analysis of EthOS and UKRI metadata; gender prediction using WIPO WGND.

The gender breakdown of funded PhDs presents a consistent imbalance. Across all years, male candidates were more likely to be funded than female graduates. Men consistently account for around 65-70% of funded projects, whilst women make up 30-35%. Although there is an increase in female funded projects, the gender gap has not narrowed significantly over the six-year period (Figure 4), a pattern that is reflected in the overall gender gap in science and engineering PhD graduates.

Even though studies highlight the impact that women have as lead researchers in producing novel and disruptive innovation projects, MIOIR’s Dr Julie Jebsen and co-authors noted the barriers and biases women face when applying for and securing research funding in the UK, particularly in STEM. Women are less likely to apply for funding, carry heavier institutional loads, and are less often listed as Principal Investigators (PIs), all of which constrain their ability to access resources and progress in their academic careers. Therefore, projects led by women are systematically disadvantaged, helping to explain why the gender gap in funded PhDs persists and raises concerns about how such disparities could reinforce longer-term inequalities in the UK research landscape and beyond.

Regional Funding Distribution

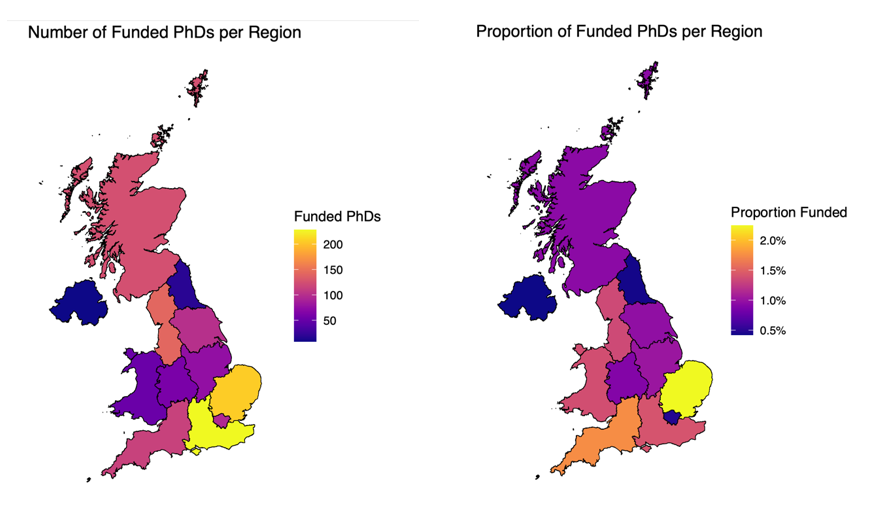

Figure’s 5 and 6 – The Total Number of Funded PhD Graduates per Region in the UK and the Proportion of Funded PhDs per Region in the UK. Source: Analysis of EthOS and UKRI metadata.

Doctoral funding is also unevenly distributed across the UK. Both the number and proportion of funded PhDs vary by region. As expected, the number of funded projects is highest in the London, Oxford and Cambridge ‘Golden Triangle’ (Figure 5). However, when considered as a proportion of total PhD theses, London’s share of funded doctorates is comparatively low at 0.5%. Whereas Oxford and Cambridge maintain higher proportions of funded PhDs at 2% (Figure 6).

Most other regions of the UK receive comparatively fewer funded projects. However, there is a slight increase in funded projects towards the North-West likely due to research universities such as The University of Manchester and The University of Liverpool. These regional disparities in doctoral training opportunities may influence participation in science and innovation, which could determine whose ideas shape the UK’s innovation economy in the future.

What’s Next for PhD funding In The UK?

Taken together, my analysis shows that doctoral funding in the UK is unevenly distributed across subjects, genders, and regions, and that these domains are deeply interconnected.

STEM disciplines, particularly Physics and Technology, consistently attract the highest levels of support, while Humanities and Social Sciences remain underfunded. This disciplinary imbalance intersects with gender, since STEM is historically male-dominated, with men accounting for approximately two-thirds of funded PhDs. At the same time, STEM funding is concentrated in the ‘Golden Triangle’ of London, Oxford, and Cambridge, reinforcing existing regional disparities.

The result reinforces a cycle in which the same subjects, institutions, and demographics repeatedly benefit, while marginalised groups remain excluded. These patterns shape who can access doctoral opportunities and whose careers are accelerated through funding, whilst limiting the diversity of voices contributing to the UK’s research and innovation landscape.

Furthermore, these disparities matter because their effects extend beyond doctoral study into the wider research workforce. Unequal access to funding risks excluding underrepresented groups from the innovation pipeline and narrowing the range of perspectives that shape UK research. Evidence suggests that gender-balanced teams have been shown to produce the highest-impact projects, while women-led projects often drive greater novelty and disruption, yet systemic barriers continue to limit women’s ability to access funding and progress into leadership roles. The regional concentration of resources further compounds these challenges, undermining levelling-up ambitions and restricting opportunities for researchers outside dominant hubs. Without deliberate intervention, these imbalances risk hardening into structural inequalities that constrain inclusivity, limit productivity, and undermines the UK’s potential to sustain its world-leading research.

Addressing these challenges requires deliberate reform of funding practices. Funders, universities and policymakers must commit to re-shaping how doctoral funding is allocated. Nesta highlights that traditional peer review can unintentionally sideline novel ideas, reinforce disciplinary orthodoxies, and perpetuate gender and regional bias. Alternatives such as randomised funding for equally qualified proposals, or more egalitarian models that distribute resources more evenly, could reduce the influence of unconscious bias and the “Matthew effect” where the same groups are repeatedly advantaged.

Universities can also trial anonymised applications, broaden eligibility criteria, and provide mentoring to support underrepresented researchers through the funding process. Nesta and the Innovation Growth Lab are already experimenting with these approaches and adopting them more widely could help create a funding system that is fairer, more transparent, and better able to support bold and diverse research. By doing so, the UK can begin to break the cycle of subject, gender, and regional inequality, and build a doctoral pipeline that strengthens its position as a global research powerhouse.

This blog was created as part of the UK DGCI project by Student Intern Emily Johnson, with help from Cornelia Lawson, Xin Deng and An Yu Chen.

0 Comments