The AI Thesis Network: A glimpse into gender dynamics of UK STEMM PhD theses

The emergence of Generative Artificial Intelligence (GenAI) is transforming productivity across various innovation-related fields through not only automation of routine cognitive tasks but also creative content generation and complex problem solving. The arrival of GenAI is also shaping discussions around the potential of AI technologies to influence existing socio-economic conditions due to their widespread adoption and far-reaching impacts. Global reports from institutions such as the Harvard Kennedy School have highlighted that women remain significantly underrepresented in GenAI related domains and decision-making roles. This macro-level gender imbalance is mirrored in the UK’s academic landscape, with limited diversity in the community of early career scientists working with AI with uneven participation across gender groups.

In this blog, we highlight trends in gender diversity observed in the early career stages of STEMM (science, technology, engineering, mathematics, and medicine) researchers, and how these may contribute to the widening of already existing gender gaps in STEMM. The blog thus sheds light on some of the potential implications of AI.

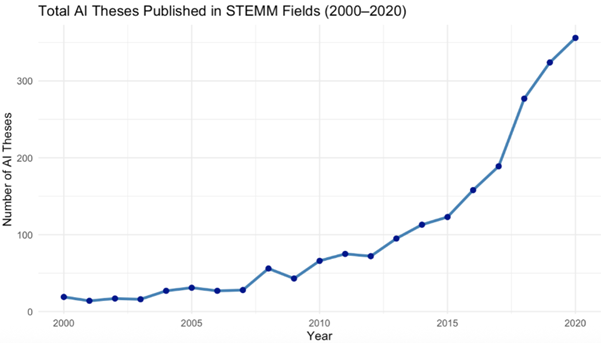

Artificial Intelligence (AI) refers broadly to computer systems that are designed to perform tasks that typically require human intelligence, such as learning, problem-solving and reasoning. Since 2015, there has been a significant rise in the number of AI-related STEMM PhD theses within the UK academic landscape (shown in Figure 1).

Figure 1: Total number of AI theses published in STEMM fields over a timeline of 2000-2020. Source: Analysis of EthOS metadata. AI definition based on Van Noorden & Perkel (2023).

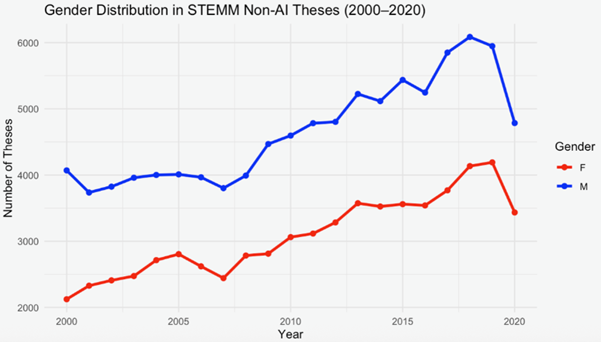

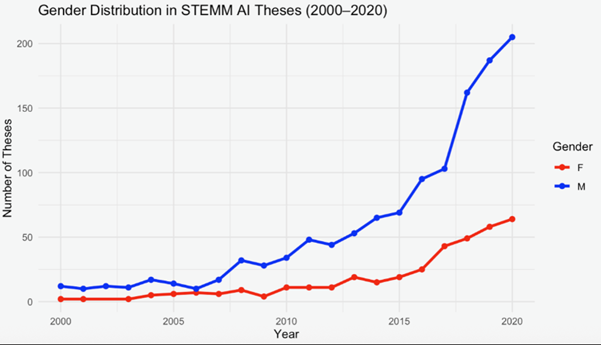

In our research we explore the gender distribution in AI-related theses within STEMM fields to assess gender disparities. From 2000 to 2020, male authors consistently outnumbered female authors in both STEMM non-AI and AI theses, with the gender gap widening more noticeably in AI-related research (Figures 2a and 2b). It thus becomes evident that while overall participation of PhD researchers in AI has increased, gender disparities persist and even widen.

Our data also shows that non-AI STEMM theses saw a sharp decline in 2020 likely due to pandemic-related disruptions, AI-related theses instead remained stable or continued to grow. This may be due to the remote-friendly nature of AI research and its rising relevance during the COVID-19 pandemic. The contrast suggests that AI is more resilient to external shocks. At the same time, it is less inclusive, deepening existing gender and access disparities. However, these trends should be interpreted with caution due to challenges in thesis classification, missing subject data, and potential inaccuracies in name-based gender prediction.

Figure 2a: Gender distribution in STEMM Non-AI theses (2000-2020); Source: Analysis of EthOS metadata; gender prediction using WIPO WGND.

Figure 2b: Gender distribution in STEMM AI theses (2000-2020); Source: Analysis of EthOS metadata; gender prediction using WIPO WGND. AI definition based on Van Noorden & Perkel (2023).

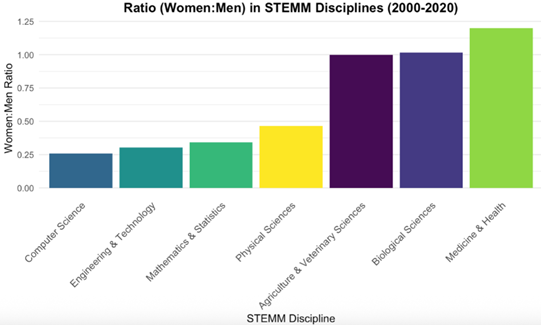

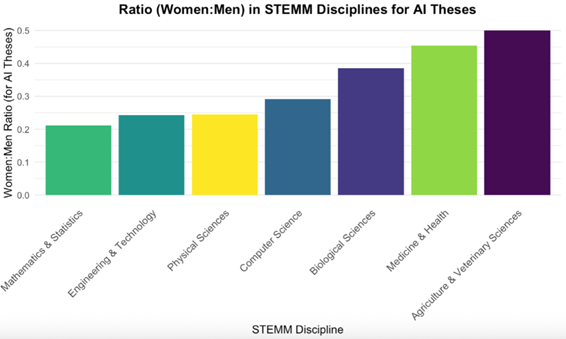

The overall underrepresentation of women in technical STEMM fields like computer science, engineering and technology, and mathematics and statistics is also observed in AI-focused research. Figures 3a and 3b reveal a surprising sharp decline in female representation in fields where broader STEMM participation is relatively balanced. These trends closely align with findings from Nesta’s 2019 study on gender diversity in AI research, which identified similarly low female representation in core technical AI areas such as machine learning, data science, and informatics. Moreover, Frachtenberg and Kaner (2022) focusing on computer systems research, found that women comprised only about 10% of authors in top-tier systems conferences—significantly below the computer science average—highlighting persistent gender disparities in foundational AI subfields. Similarly, Ding et al. (2023) revealed citation and collaboration gaps for women AI researchers, along with gendered linguistic patterns in scholarly writing, underscoring female underrepresentation in AI publishing. While these studies highlight the wider patterns of gender inequality in technical fields related to AI research, our study focuses on PhD students and presents insights about how gender disparities manifest at an earlier formative stage of the research pipeline.

Figure 3a: Relative representation of women and men in STEMM disciplines (2000-2020). Source: Analysis of EthOS metadata. Gender prediction using WIPO WGND.

Figure 3b: Relative representation of women and men in STEMM disciplines for AI theses (2000-2020). Source: Analysis of EthOS metadata. Gender prediction using WIPO WGND. AI definition based on Van Noorden & Perkel (2023).

The findings in this blog suggest that the underrepresentation of women in AI is not merely a reflection of broader STEMM participation rates, but points to structural barriers within the AI research ecosystem itself. One such barrier relates to the significant gender imbalance among PhD supervisors in AI, where male supervisors vastly outnumber female counterparts. Our data reveals that 73.4% of AI-relevant dissertations were supervised by men while only 26.6% had female supervisors. This could potentially influence mentorship opportunities, research topic selection (e.g. steering women away from AI), and access to networks. Addressing these disparities requires interdisciplinary strategies such as promoting diverse inclusive mentorship models, opening up opportunities for AI research in STEMM fields with stronger female representation, and ensuring institutional support for equitable opportunities.

Author details:

This blog is a part of the UK Doctoral Graduates’ Contribution to Innovation project and is co-authored by Sanya Panda and Emily Johnson who are research interns working with the UK DGCI team.

0 Comments