Charts, Communities and Changing Perspectives: Reflections from the 5th ISA Forum of Sociology | Mariana Hernandez-Montilla

MUI PGR Maria Hernandez-Montilla reflects on her experience at the 5th ISA Forum of Sociology earlier in the year and discovers some unexpected links between researching rural and urban policy.

As part of MUI’s commitment to supporting early stage researchers, several travel grants were awarded to enable them to present their work at global events. Maria’s blog marks the first in a new series featuring insights, learning and reflections from the recipients of this funding.

I packed my laptop with a neat PowerPoint presentation about Mexican forest restoration policies, complete with charts showing that only 4.2% of policies grant Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities (IPLCs) meaningful decision-making power. I had measurement scales, inclusion indices, and policy gap analyses—all the tools of rigorous academic research. But after attending the 5th ISA Forum of Sociology, in Rabat, Morocco, I arrived home with more questions than answers and a different perspective on my research.

I packed my laptop with a neat PowerPoint presentation about Mexican forest restoration policies, complete with charts showing that only 4.2% of policies grant Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities (IPLCs) meaningful decision-making power. I had measurement scales, inclusion indices, and policy gap analyses—all the tools of rigorous academic research. But after attending the 5th ISA Forum of Sociology, in Rabat, Morocco, I arrived home with more questions than answers and a different perspective on my research.

When numbers start to feel incomplete

The conference theme ‘Knowing Justice in the Anthropocene’ brought together 5,000 researchers from over 100 countries to grapple withenvironmental and social crises. I was there to present my analysis of how Mexico’s policies include IPLCs in forest restoration, research that revealed relevant gaps between policy promises and practical implementation.

But my session on ‘Governance of Global Sustainability Challenges’ made me pause. Listening to fellow researchers present work from Nigeria, Tasmania, and UN agencies, I realized we were all documenting variations of the same troubling pattern: formal institutions acknowledge the importance of local knowledge, and community participation but struggled to include local communities in meaningful ways.

Yildiz Atasoy from Simon Fraser University described how “agriculture by algorithm” was converting diverse farming knowledge into standardized data units. Chiebonam Ayogu’s research in Nigerian forest communities showed how even well-intentioned park management excluded local communities from decisions. Their presentations made me wonder, was my own “inclusion index” measuring Indigenous participation on a scale from 1 to 5, capturing the full picture? My index was revealing important patterns in policy structures, but were there stories and relationships it couldn’t measure?

Learning from Rabat’s streets

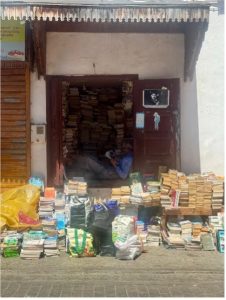

Walking through Rabat’s ancient medina everyday provided me with unexpected ideas. Here was a city where different ways of governing worked side-by-side: traditional merchant councils making decisions about market spaces, colonial-era regulations still shaping urban planning, and modern municipal authorities all operating in the same streets. Vendors dealt with these multiple systems daily, maintaining traditional trading relationships while also handling formal permits and regulations (Abu-Lughod, 1971 and UNESCO Medina of Rabat).

Walking through Rabat’s ancient medina everyday provided me with unexpected ideas. Here was a city where different ways of governing worked side-by-side: traditional merchant councils making decisions about market spaces, colonial-era regulations still shaping urban planning, and modern municipal authorities all operating in the same streets. Vendors dealt with these multiple systems daily, maintaining traditional trading relationships while also handling formal permits and regulations (Abu-Lughod, 1971 and UNESCO Medina of Rabat).

This daily reminder of overlapping governance systems stayed with me through  sessions on environmental justice and Indigenous rights. The policy gaps I’d documented in Mexico, international standards recognizing Indigenous autonomy while national policies offered only consultation, weren’t unique. They reflected global patterns of how formal institutions manage complexity by simplifying it, often at the expense of local knowledge and community autonomy.

sessions on environmental justice and Indigenous rights. The policy gaps I’d documented in Mexico, international standards recognizing Indigenous autonomy while national policies offered only consultation, weren’t unique. They reflected global patterns of how formal institutions manage complexity by simplifying it, often at the expense of local knowledge and community autonomy.

Building on what I already knew

My policy analysis had revealed something important: what I called the “implementation gap”—the difference between policy intentions and outcomes in forest restoration. This gap is real and mattered for understanding systemic barriers. But listening to sociologists, I realized this gap wasn’t only a technical problem to be solved through better policy design. It was also a social process shaped by competing visions of what forests are for and who has authority over them. This insight would enrich my analysis, particularly when exploring how communities define restoration success and what kinds of external support would strengthen rather than constrain them?

My policy analysis had revealed something important: what I called the “implementation gap”—the difference between policy intentions and outcomes in forest restoration. This gap is real and mattered for understanding systemic barriers. But listening to sociologists, I realized this gap wasn’t only a technical problem to be solved through better policy design. It was also a social process shaped by competing visions of what forests are for and who has authority over them. This insight would enrich my analysis, particularly when exploring how communities define restoration success and what kinds of external support would strengthen rather than constrain them?

From measuring to listening

The conference’s emphasis on collaborative research methods reinforced changes I have already considered for my community engagement approach. Previous research shows that restoration success depends heavily on community participation, (Chazdon et al. 2016) but too often this participation is defined by outside institutions. During my fieldwork in Oaxaca’s Mixteca Alta region during this past summer, I worked with two Indigenous communities: San Cristóbal Suchixtlahuaca and Tepelmeme Villa de Morelos, to understand restoration from their perspectives.

The conference’s emphasis on collaborative research methods reinforced changes I have already considered for my community engagement approach. Previous research shows that restoration success depends heavily on community participation, (Chazdon et al. 2016) but too often this participation is defined by outside institutions. During my fieldwork in Oaxaca’s Mixteca Alta region during this past summer, I worked with two Indigenous communities: San Cristóbal Suchixtlahuaca and Tepelmeme Villa de Morelos, to understand restoration from their perspectives.

Rather than arriving with only predetermined success metrics, I started with participatory mapping workshops where communities identified what makes restoration successful in their contexts. Instead of just measuring their inclusion in government programs, I documented how they maintain their own forest governance systems and what challenges they face. This shift from measuring participation to supporting autonomy felt right, and the sociological approaches to environmental justice I encountered at the conference confirmed I was moving in a good direction.

Connections to Manchester

Though my fieldwork focuses on rural forest communities, our panel discussions revealed how these same governance challenges play out in urban settings, particularly as climate change intensifies pressure from global to local levels. Cities and rural communities face similar tensions between top-down policy frameworks and local knowledge systems. Manchester’s climate emergency responses and green infrastructure investments (Manchester City Council. (2020). Climate Change Action Plan 2020-2025) navigate the same fundamental challenge I’m documenting in Mexican forest policy—how to create meaningful participation while working within existing institutional constraints. The collaborative approaches I’m learning from Indigenous communities might inform how we engage urban neighbourhoods in defining environmental quality and supporting local environmental governance.

What I’m taking forward

My policy analysis documented important gaps between formal commitments and practical mechanisms for Indigenous participation in forest restoration. But the conference taught me that these gaps aren’t just technical problems—they’re part of deeper tensions between different ways of knowing and governing.

My policy analysis documented important gaps between formal commitments and practical mechanisms for Indigenous participation in forest restoration. But the conference taught me that these gaps aren’t just technical problems—they’re part of deeper tensions between different ways of knowing and governing.

As I go through the data from my fieldwork in Oaxaca, I keep thinking about the questions that emerged from engaging with sociological perspectives. The conversations with researchers studying similar dynamics around the world showed me that the challenges I’m documenting in Mexico are part of broader patterns requiring collaborative solutions.

The daily calls to prayer echoing across Rabat’s skyline reminded me that knowledge and governance systems are always multiple, overlapping, and sometimes contradictory. My fieldwork showed me how communities navigate between government requirements and their own needs, how they adapt restoration approaches to work in their local contexts. Now, I need to write about this in ways that serve those communities and contribute to broader policy discussions.

I went to Rabat with charts and numbers. I’m coming back with stories and relationships. Sometimes the most important research transformations happen not in the field, but in the conversations that help us see our work differently.

0 Comments