Inclusive research is not only about recruitment

Blog written by Dr Binish Khatoon, Tree of Life research team member

Hello! I’m Binish, a data science methodologist here at the University of Manchester, and this is my first time writing a blog. I’m excited to share some insights from the project about breast health seeking behaviours amongst ethnically minoritised women in Greater Manchester and my approach to engage with the South Asian communities. I hope these reflections will be helpful to fellow researchers, students and academics.

Hello! I’m Binish, a data science methodologist here at the University of Manchester, and this is my first time writing a blog. I’m excited to share some insights from the project about breast health seeking behaviours amongst ethnically minoritised women in Greater Manchester and my approach to engage with the South Asian communities. I hope these reflections will be helpful to fellow researchers, students and academics.

As a brief introduction to the project, the aim was to develop and pilot a peer-led educational and social behaviour change campaign, with ethnically minoritised women within community groups, to increase early symptomatic presentation and attendance at screening for breast cancer.

During the study, I worked with the team to develop a comprehensive understanding of the barriers and enablers of attendance at screening and early symptomatic presentation.

As a qualitative researcher I have worked on many projects with the responsibility to engage and recruit participants often labelled as hard to reach, hard to engage. I have found that often these groups are usually people who can’t speak English as their first language and are excluded from the onset of the study down to the rigid inclusion and exclusion criteria. On this project however working with a fantastic, ethnically diverse and multidisciplinary team, I was given the freedom to design the data collection tools and apply methodologies that in my experience would work best for this project. I knew from the very beginning of these discussions, that this project was going to be different.

Many of the well-meaning methodologies in qualitative health research adopted to understand minoritised communities’ lived experiences, don’t successfully address the underlying and deep-rooted cultural barriers and enablers behind behaviours. As a result, interventions such as those aiming to target behaviour change are often a ‘one size fits all’ approach, resulting in minoritised communities feeling even more misunderstood and disregarded.

Ultimately in my experience, some of these traditional methods are reproducing power dynamics that subordinate and sometimes oppress ethnically minoritised groups and this might explain why they are unsuccessful, even if well-meaning. In research, we need to be aware of the harmful social and cultural norms that are embedded in research culture and continue to oppress those we try to build relationships and wish to engage with, for research purposes.

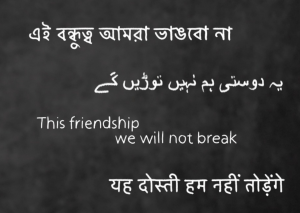

This understanding has led me to use creative arts and Narrative therapy as an alternative methodology that focuses on meeting these deeper needs for people in addressing areas such as cultural barriers, understanding emotionally triggering words, uncomfortable conversations about breasts and more. By using creative arts in this project to create culturally tailored safe spaces I have engaged with communities from the south Asian diaspora who living in Britain, sometimes as outsiders, are daily feeling isolated, ignored and filled with resentment – to release their inner thoughts and engage with strategies that help them feel safe, seen, heard, and understood in a non-judgmental space.

My aim in this research was to transform the interviewer and interviewee relationship into a friendly partnership and frequently a companionship. I wanted to find a way for the participant to feel reconnected with their inner thoughts and authentic feelings about breast health and to not feel overwhelmed by the research and academic environment and, most importantly, feel in control of their lives and open to share their authentic stories, not feeling judged or exploited.

During this research, as a British Muslim Pakistani researcher, I took time to prepare myself and reflect as an individual with my many complex intersections that make me who I am today and address my own conscious and non-conscious biases to enable me to create the authentic safe space needed to do this devotedly with these communities. Drawing on Intersectional reflexivity, which is a beacon of research accountability and transparency, I was able to move forward in my quest to develop non-oppressive relationships with these groups. I was inspired by this approach to continuously reflect and consider my positionalities during my interactions and research activities with the different south Asian communities.

My identity as an ethnically minoritised individual also was central in creating authentic non-judgmental spaces for engagement. For instance, despite sharing the same culture and religion as some of the participants in one group, participants framed my difference in educational, generational and aged terms: similarly, with other groups as a person from a different culture and religion, my heritage, age and education shaped participants’ framing of my identity, creating interesting dynamics. It was important for me to be aware of my positionality in these conversations to ensure a non-biased, non-judgemental environment and to feel accepted as a researcher into their circle of trust.

My identity as an ethnically minoritised individual also was central in creating authentic non-judgmental spaces for engagement. For instance, despite sharing the same culture and religion as some of the participants in one group, participants framed my difference in educational, generational and aged terms: similarly, with other groups as a person from a different culture and religion, my heritage, age and education shaped participants’ framing of my identity, creating interesting dynamics. It was important for me to be aware of my positionality in these conversations to ensure a non-biased, non-judgemental environment and to feel accepted as a researcher into their circle of trust.

Working towards healthcare equity requires an approach which involves community groups directly, to better understand deep-rooted cultural attitudes, but also researchers who are open to being honest to reflect and address their own positionalities and biases. The tree of life (TOL) methodology allowed me to easily reflect on intersectionality in these groups and understand the interconnected nature of social categorizations such as race, class, and gender, culture, religion as applied to these groups, creating overlapping and interdependent systems of discrimination or disadvantage. By acknowledging intersectionality as an important theoretical approach in this research, it provided me a framework for investigating breast health inequalities by highlighting intersections of individuals’ multiple identities within social systems of power.

The Tree of Life is an approach based on Narrative Therapy using the metaphor of a tree for a person’s life. It was co-developed through a partnership between Ncazelo Ncube (who was working at REPSSI at the time) and David Denborough (Dulwich Centre Foundation). Ncazelo and David initially developed this Tree of Life approach to assist colleagues who work with children affected by HIV/AIDS in southern Africa.

TOL helped foster the incorporation of intersectionality in this research in a non-judgemental environment in which participants were able to share their preferred stories in ways that made them stronger and confident. By fostering a non-blaming culturally appropriate safe space using the Tree of life approach, and through continuous researcher intersectional reflexivity, I was able to centre the participants as the experts in their own lives.

Using this approach helped participants recognise their many skills, competencies, beliefs, values, commitments and abilities that will assist them to reduce the influence of problems they identified on their trees in their lives including addressing barriers in health seeking behaviours.

These drawings of trees are far from simple art work we can glance over and forget. This is a unique insight into the lives of British Pakistani, Bangladeshi and Indian women using the metaphor of a tree. The different elements of the tree represent different aspects of their lives: the roots embrace their south Asian history, culture, background.

These drawings of trees are far from simple art work we can glance over and forget. This is a unique insight into the lives of British Pakistani, Bangladeshi and Indian women using the metaphor of a tree. The different elements of the tree represent different aspects of their lives: the roots embrace their south Asian history, culture, background.

The trunk, standing strong and tall, represents skills and abilities and often forgotten acts of kindness shown in their daily lives in Greater Manchester as mothers, wives, friends, and leaders of the home. Leaves are significant people who give them strength and provide the means to grow. Each branch is a hope and dream for the future including the vision of living a healthy life. The fruits and flowers are things that each woman has given and received. The Ladies’ trees form a forest to stand as a powerful and enduring metaphor: Symbolising courage, strength, and interconnectedness between three intersectional yet homogenised communities.

Finally, I want to stress on the point that we need data collection methods in research which do not disempower people by positioning them as vulnerable, incompetent or a problem and not adequately attending to their strengths and resources. We need to re-evaluate research systems such as inclusion and exclusion criteria and make an argument to invest into more appropriate training for researchers to be able to successfully engage with minoritised communities, authentically. Methodologies such as Narrative Therapy equip us with the tools to pay attention to issues of power and to support an alternative voice from people.

Using more appropriate research tools can be helpful in the quest for allowing people to decide for themselves if something is significant or helpful to them and their communities, asking for feedback, and exploring why certain ideas, interventions or engagement strategies are of more interest than others.

Remember – inclusive research is not only about recruitment – it’s about helping the people who do engage want to keep engaging in research and stay in your company. Participants do not have to fit into the pre-existing conditions of research- rather we need to create research environments and tools which are designed to provide support and structures that everyone needs to successfully engage and have a voice. Every voice is valued no matter the differences.

0 Comments