Policy Alignment as a Key Driver for Inclusion in Urban Areas: Insights from Melbourne

Inclusive Melbourne Strategy

Inclusion in Melbourne Innovation District

Inclusion attracts much attention in new urban development initiatives such as innovation districts. Covid-19 has prompted policy officers to consider the benefits that Melbourne Innovation District can offer to the city’s residents. The inclusion was addressed through consulting and co-designing public spaces with the members of residents. However, no explicit criteria are set to regulate the companies located within the district. Therefore, while innovative organisations are assumed to create public value, no mechanisms were developed to facilitate or direct that value creation. As one of the City of Melbourne policy officers described: “It is understood that any initiative that the City of Melbourne does should serve the community or at least consider the diversity of communities. However, it is not always explicitly written into policies”.

Contextual factors that influence the approach to inclusion in Melbourne

Understanding the best practices of supporting inclusion by Melbourne’s local government requires first reflecting on urban contextual factors that could shape that process.

1 – Governance structure

Melbourne lies in the centre of the Greater Melbourne metropolitan area and is occupied by about 150,000 residents. Unlike Greater Manchester, which has city-region and borough-level policies and strategies, the Greater Melbourne does not have a combined governing body. Instead, Melbourne (as a part of Greater Melbourne) has its own Mayor and local government, which remain independent from the local authorities of the neighbouring boroughs.

2 – Number of policies that address inclusion

Melbourne lies in the centre of the Greater Melbourne metropolitan area and is occupied by about 150,000 residents. Unlike Greater Manchester, which has city-region and borough-level policies and strategies, the Greater Melbourne does not have a combined governing body. Instead, Melbourne (as a part of Greater Melbourne) has its own Mayor and local government, which remain independent from the local authorities of the neighbouring boroughs.

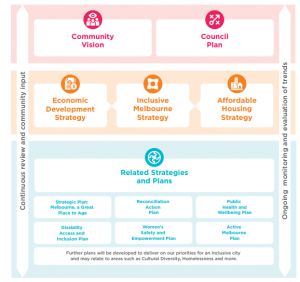

Melbourne’s lower level of governance complexity results in fewer policies and strategies related to a specific issue. Inclusion Melbourne Strategy presents a unified framework for supporting inclusion in the city, and outlines linkages between different strategies. The Strategy mentions four other overarching city strategies that support inclusion – Council Plan, Economic Development, Affordable Housing, and six related plans (Figure 1). Although the operationalisation of inclusion and proposed supporting measures vary among these strategies, the Strategy provides a straightforward representation of the position of the Inclusive Melbourne Strategy relative to other policies.

Figure 1. Key urban development strategies in Melbourne. Source: The City of Melbourne, Inclusive Melbourne Strategy (2022).

3 – Institutionalised community engagement

An institutionalised community engagement process in Melbourne significantly facilitates the implementation of inclusion initiatives at the local government level. An Acknowledgement of the Country and other forms of paying respects to the Indigenous people and First Nations promotes a greater appreciation of the interests of different communities that occupy the land. That, in turn, significantly facilitates public awareness of inclusion and its importance for Melbourne.

Strengths and weaknesses of the Melbourne approach

The main strength of Melbourne’s approach to fostering inclusion lies in the city’s overarching policy framework around inclusion. The existing framework clearly articulates the government’s understanding of inclusion and a range of policies and plans that support it. Inclusive Melbourne Strategy also strongly emphasises diversity and inclusion within the local government, The City of Melbourne. It acknowledges that organisational culture impacts the wellbeing of staff and the quality of the organisation’s services, programs and places.

However, Melbourne’s approach to inclusive growth could be further strengthened in its Economic Development Strategy, which mentions inclusion but does not present a coherent approach to inclusive economic growth. In addition, coordinating policy efforts with other municipalities within the Greater Melbourne area would amplify policy impact.

Greater Manchester’s approach to inclusion

In Greater Manchester, many policies are related to inclusion, directly or indirectly, at both the city-region and borough levels. For example, at the Manchester level, there is 2019-2022 Manchester Inclusion Strategy, which focuses primarily on inclusion of children and young people under 16 in the educational process. Our Manchester Industrial Strategy focuses on the economic aspects of inclusion. It proposes fostering inclusive growth by supporting lifelong education, closing the digital divide, reforming transport infrastructure, and enabling creative industries. Additionally, Manchester Equality Objectives emphasise Council’s continuing plans to engage with the third sector and community organisations.

At the city-region level, Greater Manchester’s Local Industrial Strategy discusses creating inclusive growth by supporting creative clusters and improving access to jobs and digital skills. Greater Manchester Digital Inclusion Agenda aims to bridge the digital skills gap among different groups of people. In turn, Greater Manchester Innovation Plan highlights the importance of collaboration of innovation-led inclusive economic growth in the region.

Strengths and weaknesses of the Greater Manchester model

Greater Manchester demonstrates a multi-dimensional approach to inclusive growth in the city-region, focusing on job creation, transport infrastructure, digital skills, and innovation. There is also an emphasis on ethical public procurement and engagement of the third sector organisations.

However, it is hard to navigate among the many strategies and policies that address different aspects of inclusion in the Greater Manchester area. Inclusion is not clearly defined, and the lack of policy alignment results in an unclear vision of what ‘inclusion’ beyond ‘inclusive growth’ means and which body monitors implementation of different activities aimed at inclusion.

Key implications for Melbourne and Greater Manchester

For inclusion to go beyond remaining a policy buzzword, policies must present an aligned narrative of urban development. I suggest several policy implications for Melbourne and Manchester.

- To avoid the dominance of economic objectives over inclusion targets, Manchester could emulate Melbourne in creating a separate inclusivity strategy, describing what ‘inclusion’ and ‘inclusive development’ could look like for the urban area and how it could be measured. Such a strategy will help build a coherent set of actions that enhance multiple aspects of inclusion so that the activity of different departments that overlook different policy domains does not contradict each other.

- Both cities could rethink wealth creation and redistribution mechanisms. Existing policies and strategies mostly fill in the gaps created by the existing systems and structures, which does not change the underlying mechanisms that led to exclusion in the first place. Rethinking wealth creation processes could involve thinking about the meaning of inclusive economy (inclusion for whom?), what actors and sectors get involved in economic activity and innovation activity (what types of organisations are engaged, what local benefits those organisations create, what kind of innovation do we encourage), and how we can shift those processes in the desired direction.

- Both cities could also benefit from creating governance structures that would help to monitor progress towards inclusive development. Such governance structures should reflect the multi-dimensional nature of inclusion and, therefore, represent the voices of different stakeholders such as public sector, businesses, voluntary organisations, and community. If inclusion is to become a goal, policies must evidence an aligned and coherent set of actions to achieve it.

About the author:

Alina Kadyrova is a Lecturer in Innovation, Manchester Institute of Innovation Research, within the Alliance Manchester Business School. Alina holds a PhD degree in science, technology and innovation policy from Alliance Manchester Business School (Manchester, UK), MSc (summa cum laude) in Governance of Science, Technology and Innovations and BSc in Computer Science from the National Research University Higher School of Economics (Moscow, Russia).

0 Comments