The Syrian Vulnerable Persons Resettlement Scheme in the UK – a successful durable solution for refugees?

Blog written by Laura von Puttkamer. Laura recently got her MSc degree in Global Urban Development and Planning from The University of Manchester. She is now working for an NGO in Mexico and runs her own blog at www.parcitypatory.org.

This blog article is based on an essay written for last year’s seminar on “Reconstruction and Development” by Jan Robert Schulz. Laura has shortened and updated it.

Introduction: 3 durable solutions

With international refugee numbers of about 16 million, according to UNHCR, there is an urgent need for solutions to this humanitarian challenge. The United Nations promote three ‘durable solutions’, which are voluntary repatriation, local integration in the country of first asylum or resettlement in a third country. These solutions are called ‘durable’ because they are supposed to end refugees’ need for protection and humanitarian assistance in a sustainable manner. However, there has been a lot of criticism regarding these solutions and their ‘durability’, mostly because they are based on finding quick fixes and not on tackling causes or needs. They also frame refugees as a problem to be solved rather than as human beings who seek protection.

More on resettlement

Out of the three ‘solutions’, resettlement used to be the most popular option after the Second World War, with almost 2 million Vietnamese boat people as the most famous example of resettlement. Resettlement entails the transfer of refugees to a state that has agreed to admit them with permanent-residence status. However, nowadays UNHCR estimates that only 1% of all refugees benefit from resettlement. But in the last years, the numbers of resettling countries (37 in 2016), as well as total resettlements, have grown substantially, from 75,000 UNHCR resettlees in 2012 to almost 150,000 in 2016 (UNHCR 2017). Half of these were from Syria.

Importantly, in resettlement refugees usually have no say in whether and where they are being resettled to – rather, this is a top-down policy with an “unspoken migration management function” (Betts 2017). However, given the right circumstances, durable solutions such as resettlement can reach their aims. By offering protection and a new life to some of the world’s most vulnerable persons, resettlement does have a vital function.

The UK offers an interesting case study for resettlement, since it operates a resettlement programme for Syrians – the Syrian Vulnerable Person’s Resettlement Scheme (VPRS). Is this a successful example of resettlement? This article will give an overview of this programme and suggest indicators to measure the success of the programme.

Of the 22 million people living in Syria in 2011, approximately 70,000 flee their country on a monthly basis (UNHCR). This makes Syrians the largest refugee population in the world with more than 4 million refugees at the end of 2014. While most Syrian refugees flee to the neighbouring countries Lebanon, Jordan, Egypt, Turkey and Iraq, the international community has also pledged to take in some of the refugees. Financially, the United Kingdom is the second-largest bilateral donor to alleviate the crisis, after the United States. By 2015, the UK had committed almost 800 million US Dollars (UK DFID in Ostrand 2015). However, it should be kept in mind that while the UK’s contribution to resettlement has increased over the last years, it comes from a low baseline and a “highly restrictionist stance of virtually every other aspect of UK policy towards migrants and refugees” (Collyer et al. 2017).

The VPRS

This article will only deal with the main one of the four avenues of resettlement in the UK that are open to Syrian citizens, the Syrian Vulnerable Persons Resettlement Scheme (VPRS). Other options are the Gateway Protection Programme, the Mandate Refugee Scheme and the Community Sponsorship Programme. The latter is based on the support of private community groups and you can read more about it in this article from the Guardian (2017).

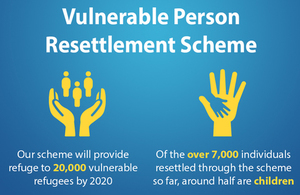

So far, the VPRS has resettled 8,0000 persons. It has been in force since 2014 and is open to particularly vulnerable refugees who are registered with UNHCR. Women and children at risk, victims of violence and torture as well as people in urgent need of medical treatment are prioritised. The decision to create this programme was a political answer to public and media pressure right after the picture of the dead child Alan Kurdi appeared in every British newspaper. This can be considered as a “strategic move to divert attention from the asylum system and on to resettlement” (Orchard and Miller, 2014). In 2015, a quota of 20,000 resettlees to be achieved by 2020 was added to the programme. This includes not only Syrian nationals but also other victims of the conflict in Syria.

Analysing the success of resettlement

A distinction between successful resettlement and successful integration has to be made. The European Migration Network (EMN) establishes quite clear indicators for the formal process of resettlement such as stakeholder communication and access to citizenship, whereas integration is harder to define and measure. The following table sums up the main indicators for successful resettlement, including integration, I found in literature. I will look into every indicator, based on an interview with a representative from Rethink Rebuild Society (RRS), a Manchester-based NGO that strives to represent Syrians in the UK.

Table 1

| Indicators for successful resettlement |

| Meeting the goal of 20,000 resettlees by 2020 |

| · Fair selection process |

| · Support of local governments |

| Protection against forced return |

| Access to civil, political, economic, social and cultural rights |

| Opportunity to eventually become naturalised citizens of the UK |

| Pre-departure and post-arrival orientation |

| Integration into new communities, including: |

| · Employment |

| · Housing |

| · Education |

| · Health |

| · Social connections and participation in society |

| · Access to language, culture and local environment |

| · Welcoming communities and public institutions |

Table 2. Own elaboration based on UNHCR 2017, EMN 2016, Ager and Strand 2008, Smith 2008

Analysis of indicators

With about 8,000 Syrians already resettled to the UK since the programme’s inception in 2014, the VPRS is on track, provided that it continues to resettle about 4,000 more Syrians annually in the years leading up to 2020. However, the NGO representative mentioned that there is some concern about the wording “up to 20,000”, which allows the government to cut the numbers if necessary.

When it comes to the fairness of the selection process, the British government has some power in determining “qualifying” refugee groups. This systematically excludes single Syrian men, which might be a response to Islamophobia by viewing Muslim Arab men as threatening rather than as victims (Turner 2017). This reflects the criticism of top-down selection, but also the securitisation policy of the UK.

The support of local authorities is vital for the resettlement scheme, since it is voluntary for authorities to pledge a certain number of places. The UK Parliament in its latest evaluation of the VPRS confirms that there are enough pledges for supporting the Scheme, but also mentions that some local authorities are concerned that there might not be enough funding (2017). Additionally, confusion and lack of experience when it comes to practical resettlement issues such as availability of school places have already resulted in some delays in resettlement (The New Arab 2017).

Protection against forced return is granted to all resettlers in the UK and there have been no exceptions. They are granted five years of humanitarian protection, including “all the rights and benefits that go with that status, including access to public funds, access to the labour market and the possibility of family reunion” (Orchard and Miller 2014). This also shows that access to civil, social, economic, cultural and political rights is given. To date, there are no contradictory reports and the interview with a representative from RRS confirmed this.

The opportunity to eventually become UK citizens is given after 10 years (EMN 2016), therefore making sure that all of the UNHCR’s criteria for resettlement are met.

It appears that the post-arrival orientation in the UK is working comparatively well for resettled refugees, whereas there is a lack of preparation through pre-departure orientation or induction. Support for newly arrived resettlees consists of a monthly allowance as well as other welfare benefits, such as individual case workers. The role of Syrian communities in the UK is crucial across most of the indicators listed above. NGOs like “Syrians in the UK” cooperate with local authorities to facilitate orientation and local integration. They also act as social connections. However, this only works in places where a Syrian community already exists. Some of the resettled refugees live in places where there are no former experiences of resettlement and experience many challenges in orientation.

It is too early to find official data on employment, housing and education opportunities for Syrian resettlees. The research project “Optimising Refugee Resettlement in the UK” criticises difficulties with education and employment opportunities. A study of resettlees to the UK under the GPP shows that even after years of living in the UK, their employment rates are below average (University of Sussex 2014). It appears that language barriers are the main reason for employment and education difficulties and simultaneously prevent participation in the society. According to the Parliament’s evaluation of the VPRS so far, the right amount of English language classes is still questionable. Since September 2016, an additional GBP10 million are available to increase the hours of English classes a resettlee receives per week from four hours to ten hours. However, as stated by the Parliament (2017), “the Department has not yet worked out what is the right amount of English language teaching to provide”. The NGO Refugee Action complains that this preference for English classes only for Syrians under the VPRS is unfair to other refugees (The Guardian, 2016).

In addition to language barriers, some administrative barriers often prevent highly skilled individuals from working in their trained professions because they do not fulfil certain requirements. These difficulties in accessing employment and education lead to the exploitation of many Syrian refugees.

Resettlement happens with the housing situation in mind, meaning that many Syrians are resettled to areas where cheap social housing is available. However, these areas are not necessarily ideal for integration and finding a community. At the same time, finding different housing options when living from welfare proves to be almost impossible, resulting refugees resorting to houses rented out by other Syrians, who tend to charge high prices.

In terms of access to health care and translation services, there seem to be no problems for resettlees (EMN 2016). However, those refugees who are survivors of torture do not receive the support and specialist treatment they need. According to the statistics, more than half of the VPRS’s beneficiaries have been victims of violence or torture, but only a few of them have been referred to specialists.

As Van Selm specifies, “the success of refugee resettlement depends very much on the integration of those refugees who are resettled with their host country and community” (2014, p. 521). The Community Sponsorship Programme (see Table 1) seems to be a first step towards welcoming communities and many local governments (like Birmingham, Cornwall or Liverpool) have informational websites on how to support the resettlement of refugees as a British citizen. While it is hard to tell how much support comes from the British society itself, the value of the existing Syrian NGOs and community groups for integration has to be emphasised once more.

Table 2

This table shows a preliminary evaluation of how the UK is doing in terms of its VPR Scheme:

| Indicators for successful resettlement | Performance of the UK’s VPRS |

| Meeting the goal of 20,000 resettlees by 2020 | On track |

| · Fair selection process | Top-down, but focused on the most vulnerable groups |

| · Local support | Yes, but confusion and funding issues |

| Protection against forced return | Yes |

| Access to civil, political, economic, social and cultural rights | Yes |

| Opportunity to eventually become naturalised citizens of the UK | Yes |

| Pre-departure and post-arrival orientation | Partly |

| Integration into new communities, including: | Overall successful (RRS Interview 2017) |

| · Employment | Little data, but challenging (due to language barrier) |

| · Housing | Challenging |

| · Education | Little data, but challenging (due to language barrier) |

| · Health | Good general health support, but lack of specialised help for victims of torture and violence |

| · Social connections and participation in society | Yes – but mostly with other Syrians, language barriers with the British |

| · Access to language, culture and local environment | Overall yes, but not enough language courses |

| · Welcoming communities and public institutions | Yes |

Table 3. Own evaluation.

Conclusion

This analysis demonstrates firstly that there is a need for more research into the UK’s resettlement programme and its efficiency and success. Secondly, it shows that there is room for improvement in the VPRS, particularly when it comes to language, employment and housing. Thanks to the support of the Syrian immigrant community and local authorities, the VPRS so far has a mixed, but overall positive balance, as confirmed during the RRS Interview. A more refugee-centric and participatory design of the programme is recommendable (Swing 2017) and would also facilitate the integration into British society.

For further improvements, the UK could learn from the successes of Canada’s resettlement programme, which to date has resettled more than 40,000 Syrians (Government of Canada, 2017). There is a strong focus on preparing before arrival and on providing social services; additionally, the Canadian resettlement programme emphasises the importance of resettlees “making and active and informed choice about resettlement” (Pressé 2008). Thorough language assessment and trainings are offered, as well as orientation on finding employment and support services like child care and counselling. Especially when it comes to pre-arrival orientation and allowing resettlees to help shape the resettlement programme, the UK can learn from Canada’s best practice example. As the British Parliament also points out in its self-evaluation, countries such as Canada make more use of private or community sponsorship in resettlement.

The analysis confirms that resettlement as a durable solution has an important role in assisting the most vulnerable refugees, but is hard to implement. Its top-down nature does not account for the dynamic nature of the refugee challenge and is susceptible to political interests. It can also act as a façade by showcasing humanitarian engagement with regards to one certain group, but thereby neglecting other refugees and other avenues of immigration like asylum. This seems to be the case in the UK, where resettlement is now the main option for refugees to enter the country. However, resettlement has always been intended as a durable solution only for the most vulnerable refugees. Since it is also a very cost-intensive process, it might be sensible to focus more on resettlement and other durable as well as new, innovative solutions in the neighbouring countries of Syria. This would support regional stability and appears to be a more popular choice for resettlees in terms of cultural similarities and less language and administration barriers. Additionally, as Orchard and Miller (2014) point out, there is a need for additional lanes of support in the UK itself, but also through a European temporary protection regime and the development of more legal routes of entry into European countries.

You can read a more detailed analysis of the VPRS by Relief Web from November 2017 here: https://reliefweb.int/report/united-kingdom-great-britain-and-northern-ireland/towards-integration-uk-s-syrian-vulnerable .

Pictures

Herefordshire: http://www.refugee-action.org.uk/project/herefordshire-syrian-vulnerable-persons-resettlement-scheme/

Geographical Magazine: http://geographical.co.uk/opinion/item/1688-refugee-resettlement-britain-s-missed-opportunities

RSS celebration: http://rrsoc.org/node/850

References

Ager, A. and Strang, A. (2008), “Understanding Integration: A Conceptual Framework“, Journal of Refugee Studies, 21 (2), pp. 166-191.

Betts, A. (2017), “Resettlement: where’s the evidence, what’s the strategy?“, in Forced Migration (2017), “Resettlement”, Issue 54, pp. 73-75.

Collyer, M. et al. (2017), “Putting refugees at the centre of resettlement in the UK“, in Forced Migration (2017), “Resettlement”, Issue 54, pp. 16-19.

EMN (2016), “Resettlement and Humanitarian Admission Programmes in Europe – what works?”, European Migration Network, Study from November 2016.

Government of Canada (2017), “Syrian Refugee Resettlement Initiative: Looking to the Future”, available online at http://www.cic.gc.ca/english/refugees/welcome/syria-future.asp, last accessed May 1, 2017.

Orchard, C. and Miller, A. (2014), “Protection in Europe for refugees from Syria”, Forced Migration, Policy Briefing 10, Refugee Studies Centre, Oxford Department of International Development,

Ostrand, N. (2015), “The Syrian Refugee Crisis: A Comparison of Responses by Germany, Sweden, the United Kingdom, and the United States“, Journal on Migration and Human Security, 3(3), pp. 255-279.

Pressé, D. and Thomson, J. (2008), “The Resettlement Challenge: Integration of Refugees from Protracted Refugee situations”, Refuge, 24(2), pp. 94-99.

RRS Interview (2017), Phone interview with a representative of the NGO Rethink Rebuild Society on May 3, 2017.

Smith, R. S. (2008), “The Case of a City Where 1 in 6 Residents is a Refugee: Ecological Factors and Host Community Adaptation in Successful Resettlement“, American Journal of Community Psychology, 42, pp. 328-342.

Swing, W.L. (2017), “Practical considerations for effective resettlement” in Forced Migration (2017), “Resettlement”, Issue 54, pp. 4-5

The Guardian (2016), “‘Madness’ of £10m English lessons for Syrian refugees”, Article from September 4, 2016. Available online at https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2016/sep/03/english-lessons-syrian-refugees, last accessed May 3, 2017.

The Guardian (2017), “UK community refugee scheme has resettled only two Syrian families”, Article from January 18, 2017. Available online at https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2017/jan/18/uk-community-refugee-scheme-has-resettled-only-two-syrian-families, last accessed April 30, 2017.

The New Arab (2017), “UK ‘long way off’ Syrian refugee resettlement target”, January 13, 2017. Available online at https://www.alaraby.co.uk/english/society/2017/1/13/uk-long-way-off-syrian-refugee-resettlement-target, last accessed May 2, 2017.

Turner, L. (2017), “Who will resettle single Syrian men?”, in Forced Migration (2017), “Resettlement”, Issue 54, pp. 29-31.

UK Parliament (2017), “The Syrian Vulnerable Persons Resettlement Programme: Contents”, available online at https://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201617/cmselect/cmpubacc/768/76802.htm, last accessed May 2, 2017.

UNHCR (2016), “UK Resettlement of Syrian refugees on track thanks to welcome from British public”, 7 September 2016, available online at http://www.unhcr.org/en-us/news/press/2016/9/57cfd0dc7/uk-resettlement-of-syrian-refugees-on-track-thanks-to-welcome-from-british.html, last accessed May 2, 2017.

UNHCR (2017), “Information on UNHCR Resettlement”, available online at http://www.unhcr.org/en-us/information-on-unhcr-resettlement.html, last accessed April 24, 2017.

University of Sussex (2014), “Research Briefing: Optimising refugee resettlement in the UK: a comparative analysis. Update two years into the project”, Department of Global Studies. Available online at https://www.sussex.ac.uk/webteam/gateway/file.php?name=research-briefing-refugee-resettlement-stage-2.pdf&site=252, last accessed May 3, 2017.

Van Selm, J. (2014), “Refugee Resettlement”, in Fiddian-Qasmiyeh et al. (eds.) (2014), “The Oxford Handbook of Refugee and Forced Migration Studies”.

0 Comments