Urban slums, land-rights and disasters

This blog was written by Daniel Richards, a student on the BSc International Disaster Management and Humanitarian Response Programme.

Are you legally allowed to live where you do? What would you do if you returned home to find your house damaged beyond repair, destroyed or even disappeared completely; how would anyone know it was your house, your land and that you had a legal right to re-build? Chances are, it would be a relatively easy task for those of us living in the UK to find out who lives where and exactly who owns what[1] by simply going online. The UK Land Registry[2] contains more than 25 million titles and accounts for more than 84% of the country’s land-mass, ensuring that records are kept and maintained regarding land and property ownership.

But what would happen if you lived in a country with poor, or non-existent records of land or property? What if you were one of the one-billion people (one-in-eight of the world’s population) who UN-HABITAT estimate[3] live in some kind of urban slum?

Rapid urban-development and land-rights

‘Dhaka Slum, Bangladesh. UN-HABITAT estimates one-in-eight people now live in urban slums worldwide.’[4]

Rapid urban development in many countries and a population shift from rural to urban centres has meant that the percentage of the world’s population living in cities has increased exponentially[5] since the 1950s, with over half of the world’s population now living in urban environments. Many countries have seen massive flows of people moving to sprawling cities which lack the infrastructure to cope.

Often, these new urban-poor are forced to live on the margins, in areas devoid of basic services or facilities, on land which is dangerous or susceptible to natural hazards. It is increasingly hard in many countries to distinguish what kinds of legal rights to the land[6] these people have, especially when the state sees many of these settlements as illegal in the first place.

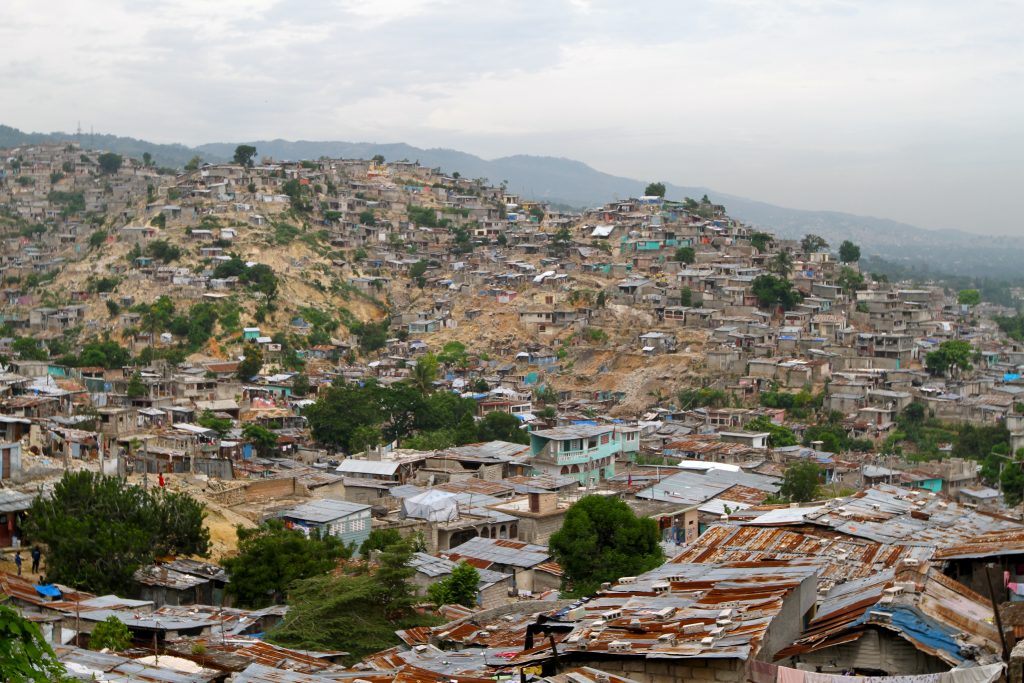

Urban development in Haiti

To put this into context, we turn to Haiti, a country which has historically been a victim of poor planning and unsustainable development, and been beset by disasters. An article by the Guardian[8] summarises many of the problems that the country has faced; cycles of exploitation, corruption, national debt, poor governance and infrastructure means that today, around 80% of the population now live below the poverty line.

In the two centuries since Haiti’s independence in 1804, disputes over tenure and land rights have been commonplace; it is estimated that ninety-five per cent[9] of all land sales in rural Haiti had been conducted without going through legal formalities and that only 40% of land-owners[10] possessed legal titles, receipts or other types of formal documentation for their land. In a country rife with problems of development and poor governance, issues such as land rights have taken a back seat.

A 2009 UN-HABITAT Report[11] notes that between 1982 and 1995, driven by economic crisis, the number of people moving from rural to urban areas in Haiti increased exponentially and that the government was unable to provide housing or basic infrastructure; squatter settlements have developed around the capital, Port-au-Prince, on unsafe land, leaving residents with little or no basic services or recognition of legal rights.

This bidonvillisation, as it has become known, of hillsides, rubbish-dumps and flood-plains has meant that hundreds of thousands of people live on land that is not only susceptible to natural hazards, but to which they can expect no state help in the event of a disaster.

The Haiti earthquake

A poor neighbourhood shows the damage after an earthquake measuring 7 plus on the Richter scale rocked Port au Prince Haiti just before 5 pm yesterday, January 12, 2009.

In January 2010, an earthquake destroyed hundreds of thousands of homes in Port-au-Prince and the surrounding areas, leaving over 200,000 dead and 400,000 homeless according to a USAID Report.[13] One of the main reasons for the extent of the devastation was the lack of regulation in the construction of buildings within the city and the adhoc settlements in surrounding areas. Many of the residents living in these ‘illegal’ settlements could expect no government assistance and those who could returned to family, to the countryside and to provincial towns.

Many more residents however, wanted to stay in Port-au-Prince, but lacked certification for land were forced out to camps outside the city where they did not want to be. Many have tried, unsuccessfully to return to their land, but without documentation, it is ‘hard for housing associations or NGOs to help them.’[14] Despite the dangers of living in settlements at risk from natural hazards, residents would rather move back, close to the city where there is work, than to the alternative housing and camps[15] offered by the government; a move which was seen as an effort to remove them from the city through forced evictions.

The earthquake in Haiti created a situation in which hundreds of thousands of people who had lost what little they had became internally displaced in their own country; forced to live in tent-cities or return to the countryside. Unsustainable urban development, poor planning and a population without rights to the land on which they live has caused chaos.

Even reconstruction efforts[16] and infrastructure projects have been affected by disputes over land rights in post-disaster Haiti. If it is hard for businesses and the government to qualify who has the rights to what land, then what hope do the residents of Port-au-Prince have? In a DEC Report[17] on the reconstruction efforts in Haiti, issues of land rights, sustainable urban development and the need for long-term housing projects to be established are put forward as essential policies, but is it too little too late? Is this something that an already poorly equipped and over-stretched government can realistically address?

Haiti and beyond…

In some countries, urban development has increased at a rate which is impossible to manage. In some cities, this has led to sprawling urban slums, in which economic migrants live illegally, in poorly constructed shelters on hazardous land, such as mountainsides or floodplains. When disasters hit, these residents, who are often not recognised as legal citizens of the city in which they live, have little to no hope of receiving assistance or rights to the land.

A focus for countries such as Haiti should be on providing legal rights, basic services and utilities to the urban poor who are increasingly moving from rural areas into expanding cities. This is not an easy task; better urban planning is needed alongside the provision of state-owned or private land for new residential areas; these need to be on non-hazardous land; systems of recording land-rights and tenures for residents need to be put in place and assistance for those who have lost their homes needs to become a priority.

References

[1] H, Adam. “How to find out who owns property or a piece of land.” landregistry.gov. http://blog.landregistry.gov.uk/find-owns-property-piece-land/ [Accessed: 26 September 2017].

[2] HM Land Registry. “About us.” gov.uk. https://www.gov.uk/government/organisations/land-registry/about [Accessed: 29 September 2017].

[3] UN HABITAT. “Slum Almanac 2015/2016.” unhabitat.org. https://unhabitat.org/slum-almanac-2015-2016/ [Accessed: 27 September 2017].

[4] Dhaka Slum, Bangladesh. UN-HABITAT estimates one-in-eight people now live in urban slums worldwide. Source: Zoriah, “0001_zoriah_photojournalist_war_photographer-bangladesh-dhaka-slum_20120817_0422.” 2012, digital image. Available from: Flickr, https://www.flickr.com/photos/zoriah/7871812586 [Accessed: 1 November 2017].

[5] UN. “Worlds population increasingly urban with more than half living in urban areas.” un.org. http://www.un.org/en/development/desa/news/population/world-urbanization-prospects-2014.html [Accessed: 26 September 2017].

[6] Payne, Geoffrey. “Urban land tenure policy options: titles or rights?” Habitat International Vol.25 (2001) 415-429. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0197397501000145 [Accessed: 26 September 2017].

[7] Sprawling urban slums close to Port-au-Prince, Haiti. Source: hollykathryn, “To Be Myself Completely.” 2010, digital image. Available from: Flickr, https://www.flickr.com/photos/holly-kathryn/4694906787 [Accessed: 3 November 2017].

[8] Henley, Jon. “Haiti: a long descent into hell.” theguardian.com. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2010/jan/14/haiti-history-earthquake-disaster [Accessed: 26 September 2017].

[9] Kushner, Jacob. “Who owns what in Haiti?” newyorker.com. https://www.newyorker.com/business/currency/owns-haiti [Accessed: 26 September 2017].

[10] USAID. “Land tenure and property rights in Haiti.” usaid.gov. http://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/PA00J75K.pdf [Accessed: 27 September 2017].

[11] UN HABITAT. “A situational report of metropolitan Port-au-Prince, Haiti.” humanitarianlibrary.org. http://www.humanitarianlibrary.org/resource/situational-analysis-metropolitan-port-au-prince-haiti-strategic-citywide-spatial-plannin-0 [Accessed: 26 September 2017].

[12] Poor construction and planning leads to devastation. Source: United Nations Development, “Haiti Earthquake,” 2009, digital image. Available from: Flickr, https://www.flickr.com/photos/unitednationsdevelopmentprogramme/4274633152 [Accessed: 3 November 2017].

[13]USAID. “Land tenure and property rights in

Haiti.” usaid.gov. http://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/PA00J75K.pdf [Accessed: 28 September 2017].

[14] IRIN. “GLOBAL: Taking on the land-grabbers.” reliefweb.int. https://reliefweb.int/report/haiti/global-taking-land-grabbers [Accessed: 26 September 2017].

[15] AFP. “In Haiti, anger over slum eviction plans.” dawn.com. https://www.dawn.com/news/738103 [Accessed: 2 November September 2017].

[16] Ferreira, Susana. “Haiti’s road to reconstruction blocked by land tenure disputes.” reuters.com https://www.reuters.com/article/us-haiti-land/haitis-road-to-reconstruction-blocked-by-land-tenure-disputes-idUSBRE90P0BM20130126 [Accessed: 27 September 2017].

[17] Clermont, Carine, David Sanderson, Anshu Sharma and Helen Spraos. “Urban disasters, lessons from Haiti.” dec.org.uk. https://www.dec.org.uk/sites/default/files/pdf/dec-haiti-urban-study.pdf [Accessed: 27 September 2017].

0 Comments