The Emotional Burden of Research

After a year and a half of preparing for my fieldwork in Malawi, which consisted of many late nights sat at my computer, reading, writing, re-writing, and drowning in ethics applications, I finally arrived in Lilongwe in April, and am now coming to the end of what has been an extremely eye-opening and emotional experience. My perception of fieldwork had always, perhaps naively, been that it is the best, most fun part of the PhD process, and while for a large part this remains true, I have also come face-to-face with some of the most emotionally challenging situations I’ve ever experienced. My research focus is HIV-related stigma, specifically exploring how this stigma can act as a barrier to health care access, and how it is affected by a sudden change in context, in the case of my PhD project, flooding.

I was always aware that my research topic is very sensitive, and after going through both UREC and Malawi’s national ethics processes, I felt fully prepared to go into the field and I was confident that I could conduct my interviews without detriment to myself, or the participant – a phrase I had ringing in my ears after two rounds of ethics applications. However, the amount of knowledge I had acquired, the theory I had developed, or the thought I had put into how to best conduct ethical research, could never have prepared me for some of the conversations I have had, and how these conversations made me feel.

Two months into my stay in Lilongwe, I found myself sitting across from a young woman, a HIV-positive sex worker. She described to me her experiences of living with HIV as a female sex worker; she told me how she had been refused health care in numerous health centres, she had been humiliated in waiting rooms by medical staff, she had been blamed for spreading diseases around her community, and she had been refused help and support when she needed it the most. The most shocking thing to me was the composure with which this woman told her story, whilst I was struggling to contain the emotion I was feeling. These experiences were not new or shocking to this woman any more, it was almost part of her daily life. I can’t really put into words how this interview made me feel, and it certainly wasn’t an anomaly; these conversations were to become quite common throughout my research.

On the opposite side, I was to encounter different types of stories, which made it difficult to maintain my neutral position as a researcher. I spoke with a lady who had been affected by the flooding, and she boasted to me about how she had barricaded the door so that a known sex worker could not get into the temporary shelter, which had been provided for the flood victims. I thought about the previous interviews I had done and felt heartbroken for these women who had been pushed out of their communities and treated as if they weren’t human. I found that I could barely muster the energy to transcribe these interviews at the end of each day, being forced to listen to these stories over again. I began to question the purpose of my research and felt so helpless. I became very aware of my short stay in Lilongwe and worried constantly about the impact, or lack of impact, that my interviews were having on these people.

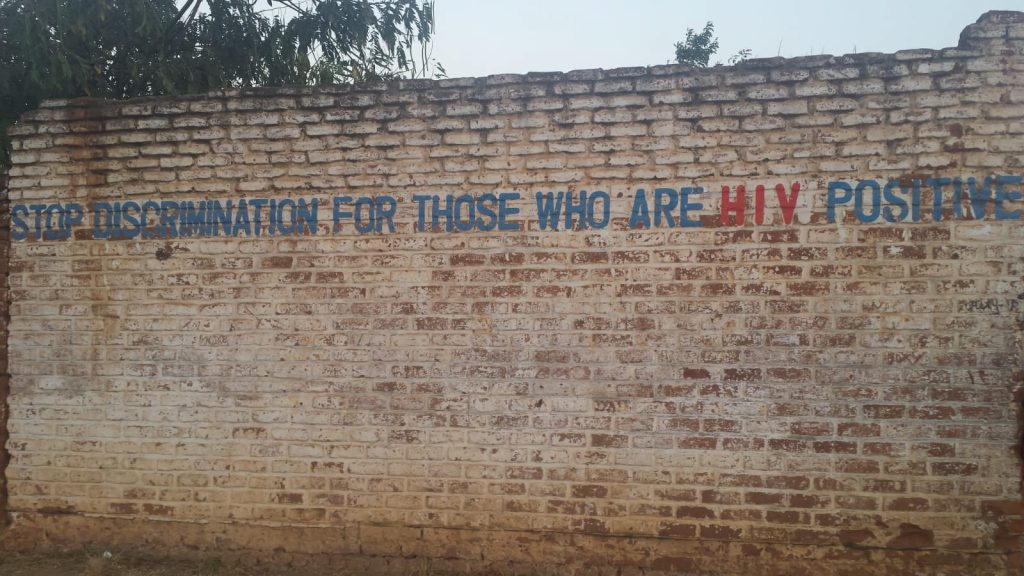

Following the advice of my supervisor, I took time out to reflect on the experience of fieldwork so far, thinking about some of the more positive findings that had come out of the interviews. Almost everyone I had interviewed had been affected by HIV/AIDS in one way or another, and the fear of infection and the discrimination of HIV-positive people, which was rife a few years ago, has started to turn to compassion, understanding, and a willingness to help and support those living with HIV. Almost everywhere I went I noticed something that was advocating for the rights of people living with HIV.

The change in attitudes towards people living with HIV still has a long way to go, but progress is being made. Throughout my interviews, this positive change has been attributed to gaining more knowledge about HIV and how damaging stigma and discrimination can be. This change now needs to start happening for key populations; those who are particularly at risk of HIV infection, but are also the most marginalised in society, such as the female sex workers I have spoken to. Knowledge is the key to change, and as a PhD student, I can contribute to this knowledge and hopefully a change in the perceptions and treatment of female sex workers in Malawi. Being able to recognise and remind myself of the importance of research has given me a new drive to hear their stories, helping me to cope with the emotional burden of my research.

This post was written by Nicola Jones, HCRI PhD student.

0 Comments