Pandemic-3.0 and the Cities Game – from crisis to transformation | Joe Ravetz

The Covid-19 pandemic has brought a multitude of deaths, the lock-down of huge populations, and the decimation of economies, not least in the UK. But here we take a forward look on cities and settlements of many shapes and sizes – not only as grey areas on the map, but as the many layered matrix for lifestyles and livelihoods. The pandemic and the immediate responses, in lockdown and distancing, decimation of public transport and others, have sucked life-blood from our cities. If and when the pandemic is contained, will the cities bounce back to the old, or bounce forward to a ‘new normal’?

Cities in this part of the world change relatively slowly, but here are there are major disruptions such as political conflict or economic collapse, and it seems the Covid-19 is one of these. To explore such disruptions, and ways to turn such crisis towards opportunity, we have to think out of the box, beyond normal limits. Here visual thinking and ‘mind-gaming’ is really useful, as part of a synergistic toolkit for problems of deeper complexity.[1] So this blog is a brief sketch with a creative angle, for the challenge of turning our urban crisis towards urban opportunity. This first instalment raises the questions, projecting what’s in motion: the next will respond with pathways for opportunities…

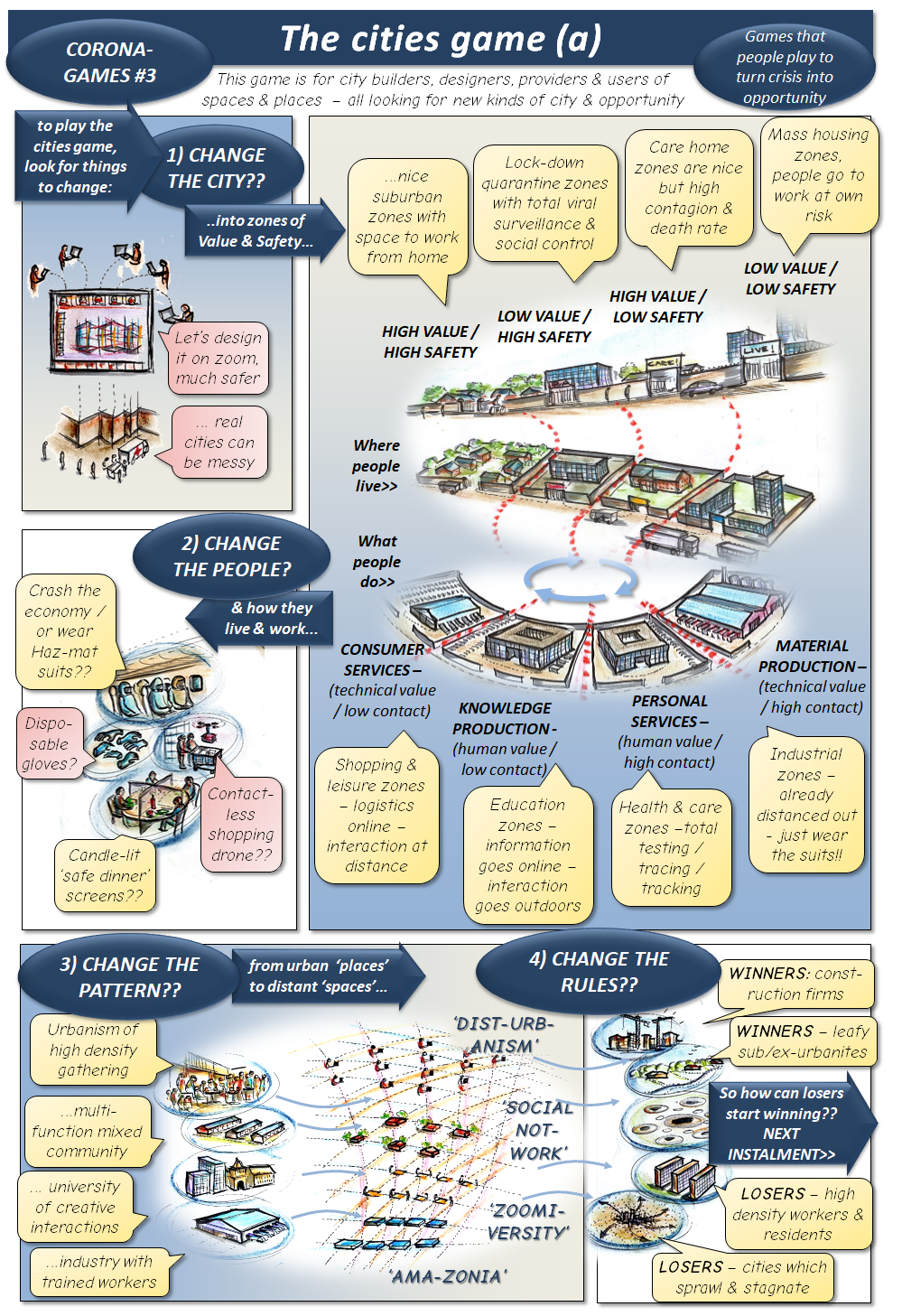

The Cities Game

The Cities Game here is one of a series, the Corona-Games, following the emerging Pandemic-3.0 agenda (see www.urban3.net ). As for the Pandemic 3.0, this is about how communities organizations or societies can learn, think, create and collaborate collectively, to turn the pandemic crisis into new opportunities – a kind of collective pandemic intelligence. This in turn draws on the new thinking in Deeper City

The Cities Game is played by city builders, investors, agents, designers, providers, managers & many kinds of users of spaces and places. Each in their way will respond to the crisis and damage and disruption, and look for new opportunities, in a kind of real-life Monopoly game. The challenge is that all too often the ‘winners’ will win more, while the ‘losers’ will lose more – in this case not only living and livelihood, but life or death itself (shown as the mortality gradient of rich and poor).[2]

This game is arranged in four key questions about what to change: the city order, the people, the spatial pattern, or the rules of the game?

The first question is how to change the ‘order’ of the city? On current trends it seems quite logical to separate out the different zones of safety and value (although going against many current principles of urban planning and urbanism). Here are some basic combinations for the residential sector:

- High value / high safety suburbs and ex-urbs – gardens and home-work-spaces for knowledge-based professionals.

- Low value / high safety quarantine zones for recent cases and incoming travellers etc, with high levels of contagion management, surveillance and social control.

- High value / low safety care homes and similar institutions, where full contagion management is difficult, and high death rates are accepted for residents and workers.

- Low value / low safety zones: high density estates and neighbourhoods, lacking private space or enclosures, where manual or high-contact workers are at higher risk.

And for the services sector:

- Material production – (technical value / high contact): Industrial zones are already distanced with social management to lower risk;

- Personal services – (human value / high contact): Health & care zones –total testing / tracing / tracking;

- Knowledge production – (human value / low contact): education and knowledge based service zones – information goes online – interaction goes outdoors;

- Consumer services – (technical value / low contact): Shopping & leisure zones – logistics online – interaction at distance.

A second type of question explores the possibility of social and lifestyle change. Will the people accept the wearing of full haz-mat suits in higher risk locations such as public transport? (and will the suits be available?) Will people go to restaurants fitted with glass safety screens?

The third question is more about the structure of spaces and places. This is not something which can be changed overnight, but if there are existing trends, such as the decline of retail high streets, the crisis and its spatial response could accelerate them, and generate new opportunities. So here are some of the key pillars of urbanism, with possible headlines for what lies ahead:

- Urbanisms of high density gathering, in dense vibrant centres of food and drink, leisure and culture. Can we look for other kinds of spaced out ‘dist-urban-ism’?

- Multi-functional mixed communities and neighbourhoods: with the disruption to jobs and services and interactions, we could talk about the ‘social not-work’…

- Universities based on creative interactions, set in a physical playground of intensive learning or campus. This sector is especially vulnerable to change, with strong pressure in the direction of a ‘zoomi-versity’.

- Manufacturing industry or logistics with trained local labour force, already under pressure to merge into the global platform of logistics and worker-free automation now known as ‘Amazonia’.

The fourth question is really to sum up the winners and losers so far, and then ask, so what?. As the pressure ramps up for lower density / higher safety living and working space, the winners will be the construction sector and those already in the desired zones. Meanwhile the ‘losers’ will be the majority in higher density / lower safety areas, along with whole cities which are likely to sprawl and dissipate. The implication is the search for positive synergies and urban opportunities for all, is ever more urgent.

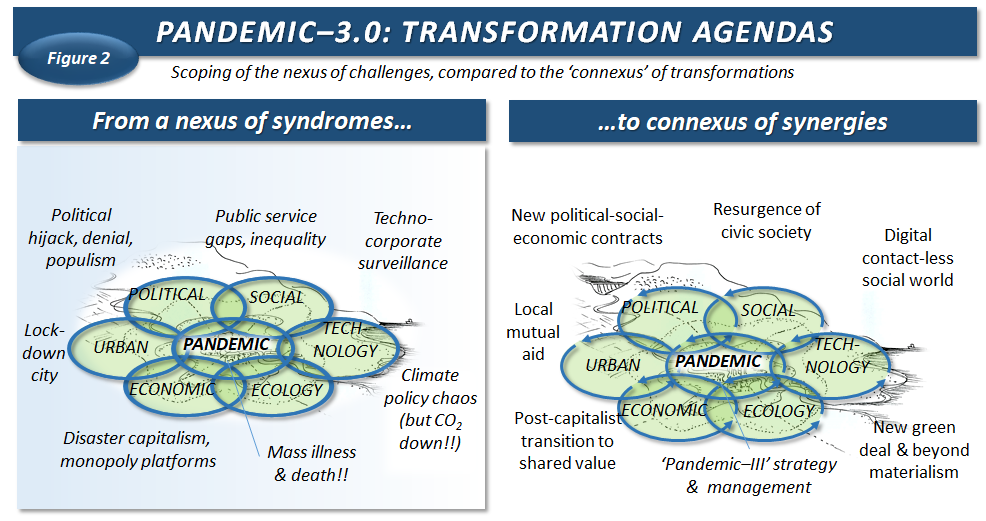

Societal transformations – by accident or design?

Meanwhile there’s a bigger picture, where cities are the spatial layer of other systems – the social, technology, economic, ecological, political and cultural (‘STEEPC’ for short). We can follow each of these domains, around the material facts of the pandemic, in the centre of a nexus of inter-connections. As sketched on the left of Figure 2, each of these involves not only material facts such as economic growth, but the underlying layers of discourse and myth between all involved.[3] And for each part of the nexus there’s also a potential counter-case, shown in the connexus on the right, where we can map out the synergies and cultivate the seeds of transformation.

In the social domain, the pandemic response locks down all forms of direct social interaction, along with one third of economic activity in service consumption: it also exposes the gaps and shortfalls in public services, and the underlying inequality and exclusion. However there’s a resurgence of social and cultural values, organizations and systems, from singing on balconies to a mass volunteering in the health service.

For technology, the door is open ever wider for techno-corporate surveillance and financial-ization: while local businesses go down, and while community apps and 3D printing emerge, the global ‘GAFA’ platforms are expanding without limit. Meanwhile in a possible future world of distancing and ‘contactless community’, the same digital platforms and networks will be indispensable.

Production in the global economic system has been through possibly its greatest ever shock and reduction of GDP, with untold suffering from the newly sick, unemployed, uninsured and homeless. However there are new patterns of part-time and home-working, along with a new questioning of materialist debt-fuelled production and consumption.

For the ecological and climate agenda, the pandemic slowdown has brought clear skies for the first time in generations, even while climate change, species extinction and toxic overload continues. While international cooperation will be more difficult, it seems possible that in a post-pandemic era, new forms of the green deal will emerge along with non-material lifestyles.

Political implications spread in all directions – the most obvious being the extraordinary acts of the state underwriting businesses and workers (in many countries) – and the most extreme where large (tax-avoiding) corporates carve up the multi-billion bailouts. Again in a post-pandemic era we look for pathways for transformation, with new political-social-economic games in play, and a potential emerging collective political intelligence.

Scientific knowledge and expert practice in a post-truth society may yet emerge as the source of trust and confidence. But the massive uncertainties in the basic science are now entangled with existential controversies: it seems post-normal science is one way to approach this, if it can link ‘science’ with other forms of knowledge.[4]

And coming back round to cities and settlements, as above the current trends are pushing towards low density, distanced, virtualized, segmented urban forms – at the same time as newly found aspirations for local communities, mutual aid and public service.

The main question here is how cities can best respond, and make the choice between alienation, and a Pandemic-3.0 kind of transformation. In this they might need the ‘pathways from smart to wise’ which are beginning to emerge: collective financial intelligence, integrated positive health systems, inclusive social mesh-works, synergistic business-enterprise models, deliberative-associative multi-level governance, and so on.

And more than any one of these, the Pandemic-3.0 agenda calls for a collective intelligence which can realize the new potential from the ashes of the old. For which, see the next instalment…

Joe Ravetz, May 2020.

[1] Waltner-Toews, D, Annibale Biggeri, Bruna De Marchi, Silvio Funtowicz, Mario Giampietro, Martin O’Connor, Jerome R. Ravetz, Andrea Saltelli, and Jeroen P. van der Sluijs. (2020) PostNormal Pandemics: Why Covid-19 Requires A New Approach To Science. Discover Society: https://discoversociety.org/2020/03/27/post-normal-pandemics-why-covid-19-requires-a-new-approach-to-science/

[2] Inayatullah, S, and Black, P, (2020). Neither A Black Swan Nor A Zombie Apocalypse: The Futures Of A World With The Covid-19 Coronavirus. Journal of Futures Studies. https://jfsdigital.org/2020/03/18/neither-a-black-swan-nor-a-zombie-apocalypse-the-futures-of-a-world-with-the-covid-19-coronavirus/

[3] ONS (2020) Coronavirus (COVID-19) related deaths by occupation, England and Wales: deaths registered up to and including 20 April 2020. ONS Statistical Release

[4] Ravetz, J, (2020), Deeper City: collective intelligence and the synergistic pathways from smart to wise. NY, Routledge. https://www.routledge.com/Deeper-City-Collective-Intelligence-and-the-Pathways-from-Smart-to-Wise/Ravetz/p/book/9780415628976

0 Comments