Media matters: how should we talk about suffering?

by Gurdev Singh

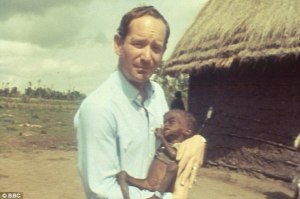

When David Cameron used the word “swarm” to refer to Europe’s refugees in 2015, a national conversation was sparked around the way in which “we” here in Britain (and in the Western world at large) talk about people from other parts of the world who are suffering. The question of how to represent suffering that is distant – in the sense of being far away and of being experienced by those who do not share in the culture of the privileged onlooker – is not a new one. But what has continued to change through the time of colonialism, the humanitarian crises of the mid-twentieth century, and that seminal report by Michael Buerk on the 1984 famine in Ethiopia, are the means by which knowledge about suffering is communicated. Thinking about how our conversations about suffering can be made more effective and more ethical leads us to question how the mode of delivery might affect the message. This was the question that I set out to answer in my MA dissertation at HCRI.

What is clear is that the way in which most people become aware of distant suffering, news reports and humanitarian appeals, are problematic. The common methods of engaging audiences may well fall flat, with reductive accounts of crises and strictly emotional depictions of sufferers doing little to challenge the unequal relationship between viewer and sufferer. Technology’s increasing ability to get us closer to the action in real time, to allow us to hear the voices and stories of those who have suffered, presents an opportunity to humanise so-called victims and in doing so break through the fatigue felt by those of us familiar with the overused tropes of disaster imagery. Such advances may allow for more empathy on the part of audiences, but is empathy desirable? If solidarity is extended only to those sufferers whose stories we are able to consume, relate to and pity, then it is a solidarity based not on justice but on the condition that the distant other satisfies our ideal of victimhood and our sense of self. Tied to this is the fact that the range of voices that find their way to our ears is limited, despite the rise of seemingly democratic forms of communication such as social media, because of inequalities that exist between the vulnerable and those of us living in the relative security of the Western world. Perhaps human dignity should entail more respect for the difference between us and the sufferer, and an understanding that our ability to relate to them and their experiences is limited.

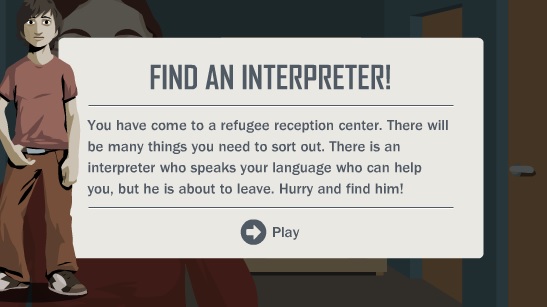

For this to be achieved, it is vital that the media do not figure the sufferer as an abstract concept. Most of us are familiar with the techniques used to make us feel towards the victims of crisis; the close-ups of mothers and children, the apocalyptic language of newsreaders, and most importantly the reductive accounts of politically complex situations. These are typical of news media, whose task it is to convey information it assumes audiences will understand in a manner that is not too partisan. The principle of neutrality may be cited in defence of campaigns that de-emphasise the causes of suffering in the attempt to generate an authoritative image (and thus more funds) for aid organisations. Those of us who remember the now infamous Kony2012 campaign will be aware of how seductive a well-branded cause can be. Leaving aside the more challenging, politically loaded facets of faraway suffering, these campaigns can make us feel good by convincing us that we are doing good, despite giving little or no indication of how our re-posts and one-click donations translate into action. Although the difficulty of making alternative media forms mainstream persists, it is in communications which are often not held to such standards of objectivity and impartiality that potential exists. The more intimate media, like writing and some genres of film, can engage our emotions while also having the space to educate and unsettle us by thoughtfully exploring the underlying structures at the heart of suffering and humanitarianism. Capturing the literary imagination of audiences through storytelling is an area in which technology can prove useful. The power of computer games to simulate the experience of violence verges on troubling, but they can also highlight the structures of inequality through gameplay. They can utilise the game emotions of triumph, failure, frustration to metaphorically detail the injustices of world systems, and thus engage users in the underlying politics of suffering (see online games like the UN’s Against All Odds or Channel 4’s Two Billion Miles for examples of this).

0 Comments