Listening to the voices of young refugees: Dr Antoine Burgard

Dr Antoine Burgard is a lecturer in contemporary history of humanitarianism at the Humanitarian and Conflict Response Institute.

In recent years, refugee children and adolescents have been at the centre of humanitarian discourses and media representations about displacement. They have also been the focus of growing bodies of work in various academic disciplines. Their visibility, however, should not overshadow that their voices are often ignored: they are what Liisa Malkki called ‘speechless emissaries’, visible but silenced.[1]

How can academics involved in refugee and youth studies avoid producing research that does not challenge this speechlessness and often reinforces it? Social scientists have developed innovative methods to include young people with refugee backgrounds in their research. For instance, here in Manchester, Caitlin Nunn (Manchester Centre for Youth Studies) has recently facilitated the creation of a zine by unaccompanied asylum-seeking young people to explore how they are experiencing their lives in the UK, especially since the beginning of the lockdown.

Historians have shared a similar ambition to give voice to refugees, but the challenges they face are, to a certain extent, different. Archives are not neutral spaces and have ‘the power to allow voices to be heard’, to highlight certain narratives and exclude others.[2] The individual and collective voices of marginalised and oppressed groups are either absent from archives or only available through the mediation of the various actors that claimed responsibility for their care and control. How can one then locate and put forward their perspectives, emotions, and modes of thinking?

In her famous 1988 essay, Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak stated that ‘the subaltern cannot speak.’[3] Scholars in refugee studies have shared similar concerns. Peter Gatrell, one of HCRI’s founding members, has asked, “who speaks for ‘the refugee’? And who is this ‘refugee’ of whom ‘we’ speak?”[4] and called for a history of displacement that genuinely addresses “the aspirations, actions, and trajectories of refugees.”[5] To do so, historians have focused on a wide range of personal testimonies. Scholars at the University of Manchester are conducting some very innovative projects illustrative of this approach. For instance, Rebecca Tipton’s ‘Translating Asylum’ puts interviews with Ugandan Asian and Vietnamese refugees at the centre. Others like ‘Reckoning with refugeedom’ led by Peter Gatrell rely on original materials such as petitions written by refugees. That kind of material is rare, even more so for children and young people, especially girls and children of colour.[6]

This scarcity of sources is a challenge I often faced in my previous work. The individuals at the centre of my research, young Holocaust survivors who migrated to Canada in the aftermath of the Second World War, were visible as objects of international charity, but triply silenced. They were refugees in a new country that did not care for their inclusion, Holocaust survivors in a community that was sometimes reluctant to listen to and value their experiences and, more importantly, young people in a world of adults.[7]

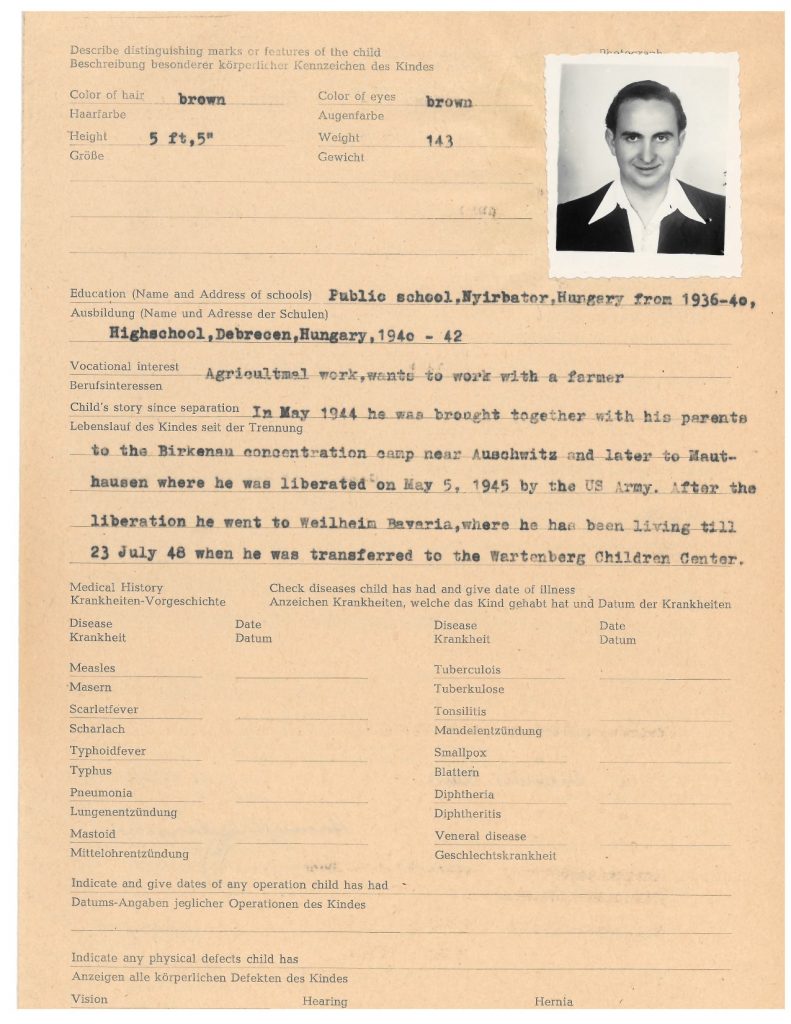

Figure 1: case file of Alexander K., august 1948 (Canadian Jewish Archives)

The vast majority of them never publicly wrote about their lives. Neither did they participate in oral history projects. One of the sources I used were the applications they had to complete to get a Canadian visa (figure 1). These two- to six-page forms have detailed information about the young refugees, their family, their experience of persecution and forced displacement, why they wanted to go to Canada and various recommendations and comments from the caseworkers who interviewed them. It is crucial to remember that this material does not give direct access to the perspectives of the individuals on which it focused. It reflects what the applicants were willing and able to recount and are the words of the caseworkers who may have misconstrued, reformulated, translated, and misunderstood the stories they were being told. However, reading them against the grain can reveal small glimpses of the young refugees’ emotions and representations, their suffering, and trauma, as well as their hopes and expectations about their new lives in Canada. One can sometimes hear their voices, however, mediated, and highlight how they often negotiated and resisted during their interactions with adults.[8]

Acknowledging and trying to challenge silences is not only important for historians and social scientists but for everyone who truly wants to listen and give a platform to the voices of young refugees and other marginalised groups. It is crucial that we question who exactly is speaking, whose voices are being excluded, who is claiming to produce authoritative accounts on their behalf, and what their agenda is.

[1] Liisa H. Malkki, ‘Speechless Emissaries: Refugees, Humanitarianism, and Dehistoricization,’ Cultural Anthropology 11, 3 (1996): 377–404.

[2] Rodney G. S. Carter, ‘Of Things Said and Unsaid: Power, Archival Silences, and Power in Silence’, Archivaria 62 (2006): 215–3.

[3] Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, ‘Can the Subaltern Speak?,’ in Marxism and the Interpretation of Culture, eds. Lawrence Grossberg and Cary Nelson (Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1988), 294.

[4] Peter Gatrell, ‘Refugees, Gender and War in Modern European History’ (2013), 10.

[5] Peter Gatrell, “Refugees—What’s Wrong with History?,” Journal of Refugee Studies 30, no. 2 (2017): 172.

[6] Kristine Alexander, ‘Can the Girl Guide Speak? The Perils and Pleasures of Looking for Children’s Voices in Archival Research,’ Jeunesse: Young People, Texts, Cultures (2012): 132-144; Nell Musgrove, Carla Pascoe Leahy, and Kristine Moruzi, “Hearing Children’s Voices: Conceptual and Methodological Challenges” in Children’s Voices from the Past: New Historical and Interdisciplinary Perspectives, eds. Kristine Moruzi, Nell Musgrove, and Carla Pascoe Leahy (Basingstoke: Macmillan, 2019), 1–25.

[7] Antoine Burgard, ‘Visualising Holocaust child-survivors in Canada: from post-war humanitarian campaigns to national memory’, Cultural and Social History (online, 2019).

[8] Antoine Burgard, ‘A traumatic past in the far distance: narrating children’s survival in the immediate aftermath of the Holocaust’, Journal of the History of Childhood and Youth, 13, 3 (2020, forthcoming).

0 Comments