Community or Corporate Control? Insights on Luke Yates’ “Platform Politics”

Mingwei Zhang, Wangshu Liu and Guyeon Kang on the politics of digital platforms

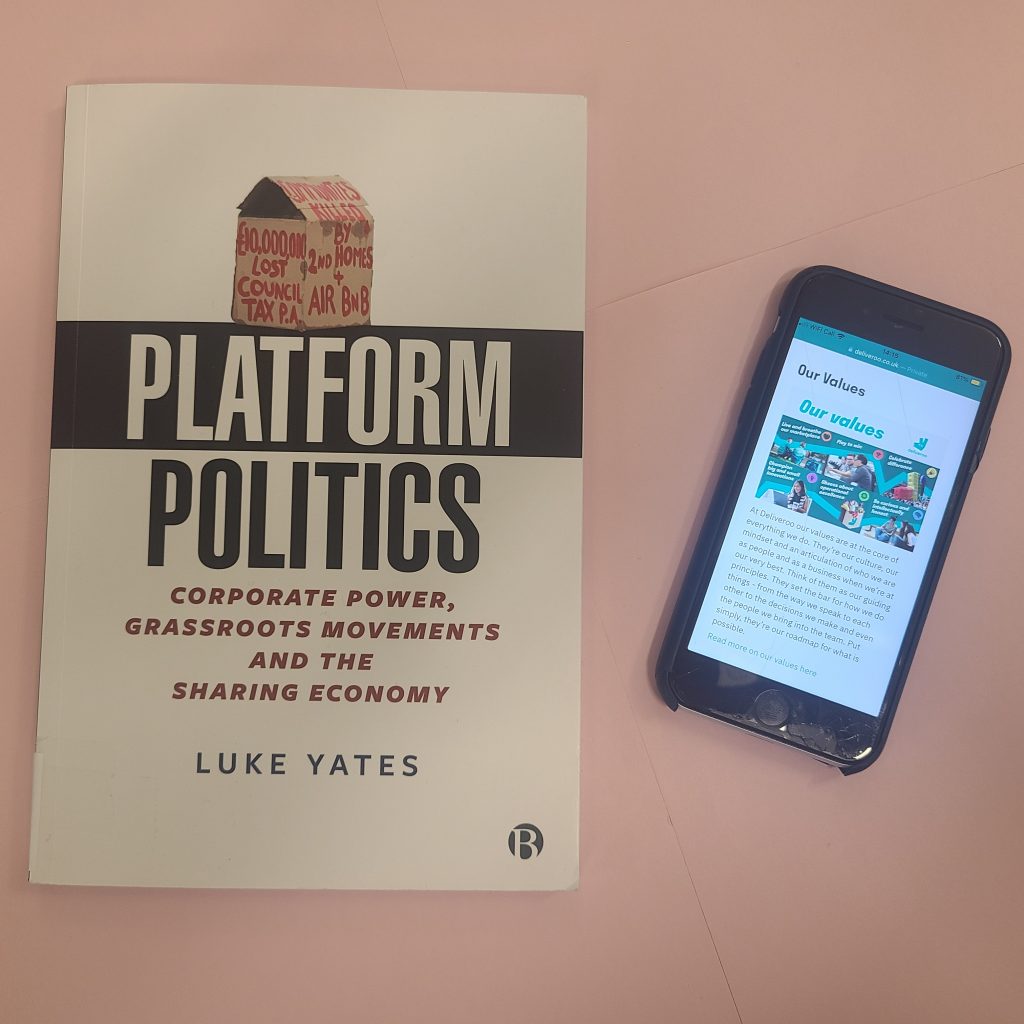

Luke Yates’ new book, “Platform Politics: Corporate Power, Grassroots Movements and the Sharing Economy” (2025), examines the governance and power of so-called lean platforms—companies like Airbnb, Uber, and Deliveroo that act as digital business intermediaries. The book explores the socio-economic transformations driven by these platforms, focussing particularly on the tactics they borrow from social movements to sidestep regulation and legitimise their business models under the pretense of community empowerment. We invited three PhD researchers working on topics such as social transformation, platform economy, environmental sustainability, and social movements to reflect on the key insights of the book.

Mingwei Zhang, PhD researcher at the AMBS

Over the last decade, the rise of the platform economy has sparked widespread debates across diverse disciplines in social sciences. This surge in interest stems from the pressing questions platforms pose: how do profound societal transformations come about? And more specifically, how do platform companies shape governance, power and public perception? While there are a few dominant narratives in platform studies—such as the concentration and monopolisation of corporate and market power, the inevitability of digital technology and technological revolutions—these narratives of the platform economy and platform capitalism often focus on abstract critiques without delving into the lived processes of change on the ground.

Luke Yates “Platform Politics” fills this gap by providing a nuanced exploration of how platform businesses, particularly “lean” or “asset-light” platforms like Airbnb and Uber, actively shape and are shaped by socio-political and techno-economic rules and structures. Yates shifts the focus from broad structural narratives of platform politics to tactics and processes through which platforms interact with communities, users and regulators. For instance, the book looks into the controversial ways platform businesses recruit, train and mobilise users and communities. These tactics blur the line between civic engagement and corporate lobbying, creating a novel and increasingly common form of legitimacy for platforms to operate. Such strategies present platform movements as democratic initiatives while serving private and investor interests.

In “Platform Politics” Yates is calling for alternative platform models, reminding us that users and civil society are not passive pawns but can organise against exploitative rules and unjust practices—timely insights for an age of big tech monopolies and tech oligarchs. To address societal challenges posed by the platform economy, a potential synthesis of “Platform Politics” with platform capitalism narratives that emphasise the market, economic, technological and infrastructural dimensions of platform power might be a promising avenue.

My own PhD research on the platform economy and the pervasive and rapid societal platformisation in China can draw insights of the “Platform Politics”. While the focal processes, arenas, actors and dynamics in my study differ in scope and scales—my thesis emphasises the Chinese state and state central planning, co-evolution between platformisation with other large and networked infrastructural systems, oligopolistic competition among big tech companies and the structuring role of the digital system in employment, consumption and urban development—the causal mechanisms book explored are still highly relevant. These causal mechanisms and processes centred on power, resources, social skills and collective actions stimulate my own reflections on the interplay between global structural developments and local agentic actions. They remind me to look for potential arenas and sites for resistance and consider “what could have been” through social movements and collective actions. Through this reflexive exercise, I hope my research can offer more constructive solutions and plausible pathways to more desirable and democratic alternatives, beyond just academic critiques.

Wangshu Liu, PhD researcher at the School of Social Science

The rise of new technologies has paved the way for the emergence of digital sharing platforms, like Airbnb and Uber, which greatly influence how we live, work and interact. These flourishing “lean platforms” serve as the intermediaries between producers and consumers, while usually holding minimal physical assets. By positioning themselves as innovative disruptors, these platforms challenge traditional regulations and exploit gaps resulting from the lag in policy responses to advance their interests, often using euphemisms like “sharing” and “community” to mask their exploitative practices. In “Platform Politics”, Luke Yates examines how these businesses wield platform power to shape governance, public opinion, and social norms, offering a comprehensive analysis of this new phenomenon.

The book’s core focus is on platform power, a term used to describe the unique ways in which platform businesses blur the boundaries between corporate lobbying and grassroots activism. It provides a deeply insightful exploration of how companies like Airbnb and Uber mobilise both consumer and non-consumer actors—such as NGOs, community leaders, and media consultants—who are co-opted into campaigns that appear independent but are carefully controlled. Unpacking the concept of “corporate grassroots lobbying”, the book reveals how platforms craft personal stories, promote curated communities, and collaborate with local organisations and opinion leaders to legitimise their campaigns. These tactics exemplify how platforms reshape governance and public perception to advance their corporate interests. For example, Airbnb launched an initiative called “Airbnb Citizen”, which mobilised hosts to advocate for policies favourable to the company. These campaigns, framed as community-led, were carefully orchestrated – Airbnb selected hosts with relatable stories while excluding large-scale commercial landlords to maintain a “grassroots” image. In the case of “Proposition F” in San Francisco, Airbnb spent over $8.5 million to oppose stricter rental regulations, organise host rallies, and media appearances – all coordinated by the company’s policy team to appear as spontaneous civic activism (Alba 2015, cited in Yates 2025).

Specifically, what’s really eye-catching is the dual nature of these mobilisation efforts—they mimic “democratic” practices like those of civil society, while at the same time being strictly controlled and orchestrated to hide the businesses’ profit-driven motives. The book explores this tension through rich discussions, supported by detailed case studies – such as Airbnb’s campaign in San Francisco – and insights from interviews with former Airbnb public policy staff. These accounts offer valuable insider perspectives on how such tactics were carefully adapted to different national and regulatory environments, reinforcing the contrast between the platforms’ public narratives and their underlying corporate strategies.

Guyeon Kang, PhD researcher at the School of Social Science

Born out of Silicon Valley’s philanthropic innovation is the rhetorical promise that digital platforms will be the panacea for the ills of contemporary neoliberal economies. Tech-giants like Airbnb, Uber and Deliveroo among others capitalise on such promise. The Sharing Economy tings the ethos that every one of the participants – from workers and housing and car owners, lay consumers to corporations themselves can share the benefits of the platform economy (Yates 2024: 1).

Yet, standing behind this feel-good promise of the sharing economy is platform capitalism and power. The sharing economy is something ardently pitched as a “good thing for cities and a good thing for citizens” (Yates 2025: 2) to quote Douglas Atkin’s words, former Head of Global Community at Airbnb, a pivotal figure who played an instrumental role in designing the idea of mobilising a landlord community to keep the lean platform business model of Airbnb rolling. Lean platforms refer to “digital intermediary businesses which play a role in connecting and matching producers and consumers, the businesses themselves holding few or no assets” (Yates 2025: 3), such as Airbnb, Uber, Deliveroo, Amazon Mechanical Turk, OnlyFans to name a few. Yates’s book fervently unearths how the platform-tech giants, to avoid regulation, conveniently appropriate tactics that resemble those traditionally deployed in civic social movements.

Digital platforms bring a number of actors together into corporate governance practices to resist regulation. Among the actors include the tech-giants themselves, practitioners on the ground such as Community Organisers at Airbnb Citizen, and both benign and commercial landlords. Yet, tech-giants artfully displace themselves from the regulatory struggle. Instead, they configure a proxy. Airbnb Citizen is one such illustrative case. Airbnb Citizen is platform-based corporate grassroots lobbying (Yates 2025: 74) (On the subject of CGL, see further Yates 2021, 2023). The community of Airbnb Citizen is organised around carefully selected landlords, with commercial landlords purposefully excluded, to curate a more benign narrative. The narrative that substantiates Airbnb’s claims to “‘democratise’ travel, capitalism and tourism revenues, with its PR and organizing efforts” (Yates 2025: 48). The mobilisation is pulled together via practices of Community Organisers, hired professionals whose career trajectory is rooted in electoral campaigning, non-governmental organisations and charities (ibid: 1).

This public arena transforms into contested politics with the power differences among the actors populating the space of lean that platforms ushered in. That is, the political has closely to do with the discursive nature of how platform tech giants curate rhetorics heavy-handedly with their power. Regarding how platform corporates manufacture rhetorics with power, Chapter 4 provides the analytic frameworks of tactics performed by the corporate actors, which are at the bottom line enabled through corporates’ exploitation of customer data. Such performances culminate into what has been dubbed the Sharing Economy, a neologism conjured up as a corporate device (ibid: 108-9) whose purpose is to keep the main source of corporate revenue intact (ibid: 94), rather than representing the voice of the civic.

Yet, Yates’s critical investigation, simultaneously, comes through as caring, warm and firmly grounded on the ground. The collaborative endeavours across an academic to practitioners on the ground (e.g. Community Organisers at Airbnb Citizen) strive to reclaim the traditional sense of social movements, which is appropriated by tech giants through the strategy of corporate grassroots lobbying (CGL) initiatives. Readers get to hear the “mixed-feelings” (Yates 2025: 89) expressed by a number of Community Organisers about their work. Nic, East Coast US-based Community Organiser perceived her work as “a dampener on the idea of collective organizing and collective movements” (ibid: 90). Largely, the feelings were stemmed in the cognitive dissonance that when community organising and activism is supposed to serve the common good of the society, their day-to-day responsibilities, including curating storytelling (Chapter 5), are designed to legitimise the corporate authenticity (ibid: 89-91).

It is of importance to delineate whose perception behind the Sharing Economy we are consuming as it is ever growing as a force to reconfigure building blocks of everyday life, such as the housing issue, in favour of the interest of platform-tech corporates.

References:

Yates, L. (2021) The Airbnb ‘movement’ for deregulation: how platform-sponsored grassroots lobbying is changing politics. Ethical Consumer. Available at: https://research.ethicalconsumer.org/research-hub/ethical-consumption-review/airbnbs-growing-political-power

Yates, L. (2023) How platform businesses mobilize their users and allies: corporate grassroots lobbying and the Airbnb ‘movement’ for deregulation. Socio-Economic Review, 21(4), 1917–1943.

Yates, L. (2025). “Platform politics : corporate power, grassroots movements and the sharing economy”. Bristol University Press.

0 Comments