Repair Week in Action: Fashion Activism, Upcycling, and Sustainable Solutions

Photographs provided by the blog author.

Tetyana Solovey, marking Repair Week, discussing the role of makers and upcyclers in solving fashion industry problems.

Repair Week, first introduced in 2020 in London, has since spread across the UK. The theme for 2025 is ‘Repair Revolution’.

From Mending to Movement: “Clothes need not cost the Earth”

Pledge Ball Gown / New Mills Fashion Activistas

New Mills Fashion Activistas is a group of concerned consumers from New Mills. “Activistas”—a play on the word “fashionistas”—do like clothes, but they don’t like how much they cost the planet and want to do something about it. Beyond repairing, mending, and upcycling for themselves, they are keen to engage others in the dialogue of how we can do better as consumers. One of the most popular photographs on their social media shows four of them in front of a mural featuring Vivienne Westwood, a designer who dared to challenge issues of modern slavery and the ecological impact of fashion production long before sustainability became fashionable.

They hold talks, mending, and remaking workshops, but one of their main activities is New Mills Fashion Week. They started it during the COVID pandemic—at first, it was online, mainly focused on talks and conversations, and later moved offline. A key part of the event involves guests sharing stories about special pieces of clothing they own. The main highlight is a fashion show featuring upcycled garments they have made themselves. Interestingly, it mirrors haute couture fashion shows—where the most skilled, predominantly handmade, one-of-a-kind garments are showcased—of the nascent era before fashion scaled up after the 1960s. The show is held in daylight, without music, with a speaker reading descriptions of each upcycled garment, telling the story of where it came from (a charity shop or someone’s wardrobe) and how it was remade.

Strawberry Thief, or still crafting a solution to industry problems?

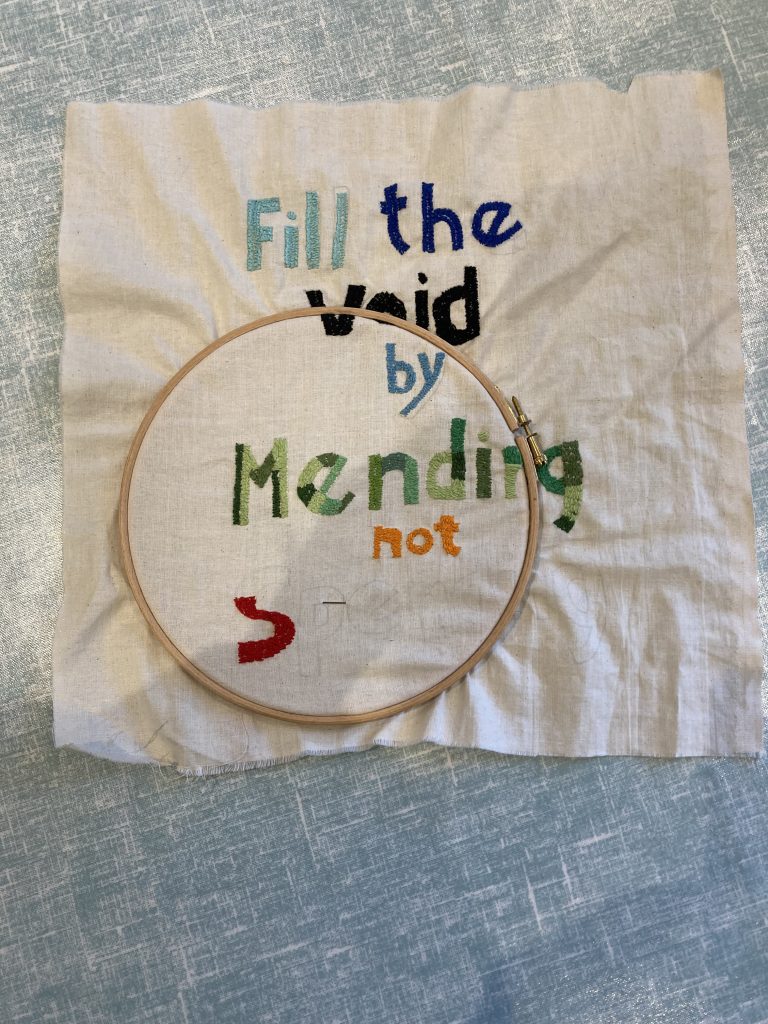

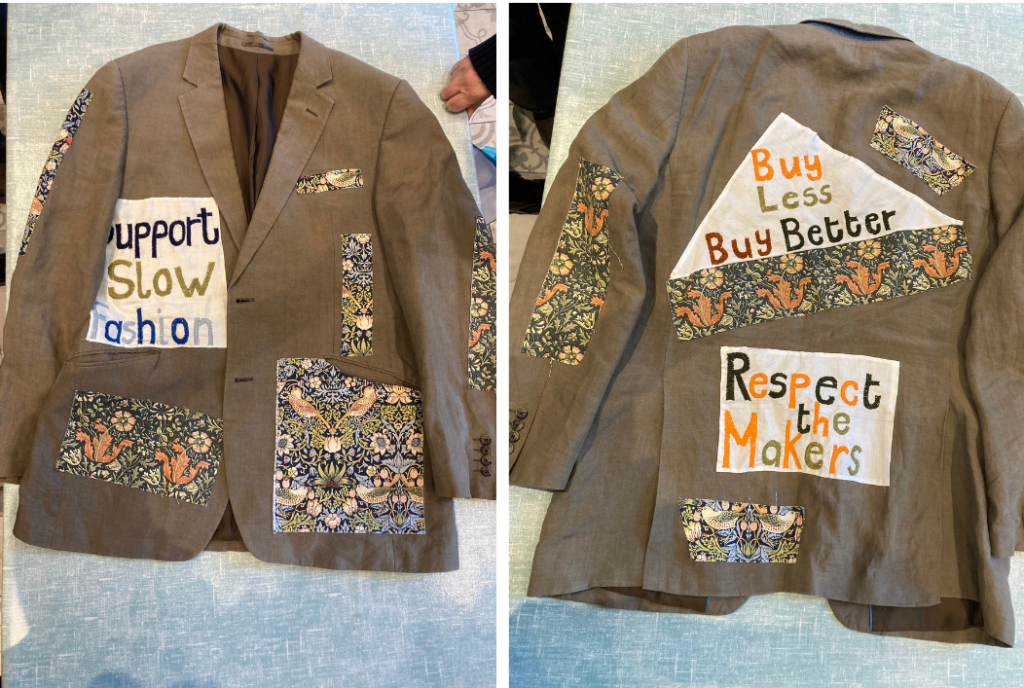

“Buy Less, Buy Better” upcycled jacket / New Mills Fashion Activistas

There are plenty of stories behind what they call their “message-spreading” clothes. One example is a denim jacket with embroidery in the style of Kusama waves, featuring lace appliqués at the top and the embroidered slogan “Respect Workers.” Another is a “Pledge Ball Gown” made from sacks, decorated with pledges from audience members who promise to repair their clothes, only buy what they truly need, or dust off their sewing machines. One dress, made from an upcycled sari, is printed with quotes from the Liverpool-based artists Singh Twins’ project “Slaves of Fashion”, which explores colonialism, ethical trade, and consumerism in textile history. Another example is a linen jacket with patches featuring William Morris’s famous “Strawberry Thief” print and embroidered with Westwood’s well-known quote: “Buy Less, Buy Better”.

What a delight! A fashion designer-activist and a Victorian Arts and Crafts visioner and Marxists—Westwood and Morris—in one piece! I was once surprised to learn that William Morris’s aspiration to create meticulously crafted, beautiful objects wasn’t at odds with his socialist beliefs in equality. He sought to combat the ugliness of capitalist society by proving that mass production could be beautiful. He also believed in the power of craft to improve the system—helping people appreciate labor rather than feel alienated from production. This idea was central to many Arts and Crafts practitioners, particularly women, who aimed to teach children from underprivileged backgrounds skills that could lead to decent-paying jobs.

It seems that skilled labor and craft still hold potential solutions for the problem of modern capitalism’s overproduction of clothing. Upcycling is a design-based approach to working with pre-consumer and post-consumer textile waste (Fletcher, 2014)—those unsold (deadstock) and unwanted pre-loved clothes that we need to deal with rather than dumping into landfills. Importantly, upcycling requires skilled labor to remake garments: transforming the UK’s approach to reuse could create over 450,000 jobs across the country by 2035 (Green Alliance, 2021). Beyond that, it’s also a skill that can be learned for domestic use, making it an accessible routine for anyone willing to learn. Upcycling is not a new phenomenon—it was once a normal household practice before machine production took over.

Nowadays, upcycling seems to be shifting from a niche practice to mass consumption—to some extent. On my way to meet the New Mills Fashion Activistas, I stopped by a charity shop and saw a Shein jacket that looked like it was assembled from two different ones—as if it were an upcycled piece. In the world of fashion prophecy, when something appears in fast fashion, it’s a sign that it has already entered mass consumption. Importantly, not just mass consumption, but premium fashion as well. The high-end upcycling fashion brand Bettter is selling upcycled T-shirts—literally made from two stitched-together shirts—for £160. Why not! Upcycled clothing can be sold at the same price as other high-end fashion products, as fashion is about design, quality of the execution, and the story behind it. Upcycling is no longer a one-off practice; for some brands, it is a central strategy, while for others, it is part of their commitment to reconsider textile waste through repurposing.

These observations from my PhD research fieldwork on upcycling—from fashion designers to grassroots initiatives like New Mills Fashion Activistas—align with scholarly discussions about making and craft as a way to reclaim production within capitalism, a “de-commodifying process” (Cassar, R., 2024: 15). This approach is promising for designers enterprises, as it enhances the ethos of makers as a core value for designers (Thomas, 2020). It is equally significant as a form of “quiet activism” (Hackney, 2013) within community making and repairing, which opens up possibilities for sustainable behavior in everyday life and as a means of resisting mass production by shifting “production processes back into the hands of everyday people” (Collins R., 2018: 166).

References:

Cassar, R. (2024) ‘Innovative Upcycling: The Creative Potential of Collaborating with Degraded Materials’, Fashion Theory, pp. 1–25. doi: 10.1080/1362704X.2024.2402111

Collins R. (2018). ‘A sustainable future in the making? The maker movement, the maker-habitus and sustainability’, in Price, L. and Hawkins, H. eds. Geographies of making, craft and creativity. Abingdon, Oxon ; Rutledge, pp 165-181

Fletcher, K. (2014). Sustainable fashion and textiles: design journeys. 2nd ed. Abingdon: Routledge.

Hackney, F. et al. (2022). Changing the world, not just our wardrobes: a sensibility for sustainable clothing, care, and quiet activism. In Routledge eBooks. United Kingdom: Routledge, pp. 111–121.

Green Alliance (2021). “Green Alliance policy insight”. Available at: https://green-alliance.org.uk/press-release/transforming-approach-to-repair-and-remanufacture-would-create-thousands-of-jobs-and-help-define-levelling-up-report-finds/ (Accessed 8 November 2023).

0 Comments