Reflections on conducting fieldwork in the Occupied Palestinian Territories

This blog was written by Emma Keelan, a Master’s student on HCRI’s online Global Health programme.

When embarking on a Master’s dissertation involving a period of fieldwork, many factors need to be considered. Developing a project idea, the creation of timely and relevant research questions, deciding on a suitable methodology and ethical approval are key. Often our universities are there to guide us with these particular concerns, providing helpful tutorials and supervisory comments as to how to overcome these challenges. So too do they provide a list of do’s and don’ts regarding fieldwork, encouraging us as researchers to consider concepts of physical risk and personal safety through lone worker policies, and stipulating the need for practical safety assurances through the provision of travel insurance.

Presently, I am in the Occupied Palestinian Territories, on a period of field research for my Master’s thesis in Global Health. When embarking on this period of fieldwork, it is fair to say that I felt a little overwhelmed, with many of my concerns remaining unaddressed in advance of leaving. Fears relating to financial support, apprehension regarding gender issues as a female researcher, provision of suitable accommodation, access to healthcare in the event of illness and perhaps, most crucially, the propensity for my research to fail, have coalesced to bring about significant personal anxiety. Additionally, I have had feelings of apprehension and vulnerability, stemming from the fact that my research involves the Occupied Palestinian Territories. Despite being an area I am familiar with, having lived here for over 12 months previously, the region remains blighted by conflict and subject to spikes in violence. Subsequently, I was concerned that this would impact on my ability to conduct pre-arranged interviews, given I only had 4 weeks in the field. Whilst fieldwork generally is associated with many difficulties it has to be said that working against a backdrop of conflict certainly makes things more unpredictable.

It is perhaps unsurprising therefore that Shaffir and Stebbins (1991) described fieldwork as one of the ‘more disagreeable activities that humanity has fashioned for itself’ noting that it is ‘usually inconvenient, sometimes physically uncomfortable, frequently embarrassing, and to a degree, always tense” (p. 1). These words have resonated many times with me during the past month away, whether it be as a result of navigating the 35 degree heat, being caught at closed checkpoints with no food, water or bathroom facilities, or merely inconvenienced when interviews are cancelled last minute. However, whilst this description of fieldwork proffered by Shaffir and Stebbins is definitely relevant, I have come to realise that fieldwork also has impact on a more personal level, particularly in relation to researcher wellbeing and mental health.

Loneliness can be particularly pronounced, a consequence of being away from family and support networks and exacerbated by often being the ‘other’, due to different cultural practices. Moreover, feelings of inadequacy are exacerbated by listening to distressing narratives from research participants or stemming from personal anxieties regarding deadlines or the relevance the work at hand. My methodology includes discussions with Palestinian female respondents regarding their daily challenges living under occupation. Such conversations, despite the upbeat nature of the respondents, expose issues such as gender disparities, violence and the challenges of growing up in refugee camps, where limited access to health and amenities prevail. For me as a researcher, such conversations unmask and sharpen (rightly so) my feelings of privilege as a white non-Palestinian woman. Whilst I am beyond grateful for the honesty of the interviews, they engender a level of personal anxiety regarding the appropriateness of my presence within the region and my work more generally. Similarly, it can be difficult to find the words to express my feelings regarding at times harrowing personal narratives to friends and family at home who have little understanding of the region, all whilst maintaining confidentiality. This inability to confide, has at times, engendered a heightened sense of isolation.

My period of research has coincided with a series of key events within Palestine, namely the relocation of the US embassy to Jerusalem, the Great return marches in Gaza and the 70th anniversary of the Palestinian Nakba. Correspondingly, I have witnessed an escalation in violence which has resulted in increased checkpoints and roadblocks. Travel times to and from interviews have been affected, and journeys which should take one hour have, on occasion, increased to four. Whilst not unusual, the subsequent exhaustion has generated a sense of apprehension regarding whether I will have enough time to secure my methodology’s stipulated number of interviews. This takes on even greater significance as I am doing this research whilst taking annual leave from my day to day work in the hospital back home. Time is an issue further compounded by Ramadan, with potential respondents sleeping during the day as they fast, which has resulted in interviews again being cancelled last minute due to the respondent’s fatigue.

Yet perhaps the most difficult aspect of research to date has stemmed from the bombardment of news stories and images from Gaza, where over 60 people have been killed to date. Whilst this was not completely unexpected given precedent within this area, the impact and extent of the violence has affected me quite significantly, despite not being exposed directly. The receipt of personal messages from family and friends concerned about my safety are juxtaposed against the experiences of those in Gaza who have lost someone close. Consequently, I have felt a sense of powerlessness, and subsequently have found myself withdrawing inwards, reluctant to engage on Facebook or Skype with friends and family, as I attempt to process the events, and begin reconciling my work against something much larger.

I don’t believe my fieldwork experiences are unusual, and despite the potential for fieldwork to impact researcher mental health and wellbeing, there remains a paucity of literature discussing these issues openly. In one of the more frank accounts of fieldwork, Browne (2013), reflecting upon his difficulties as a lone researcher in the Occupied Palestinian Territories, acknowledges feelings of vulnerability, loneliness and personal anxiety, from the daily challenges of negotiating with military apparatus and prolonged periods away from family. Interestingly, he also highlights the effects of fieldwork upon his family at home, highlighting their anxieties regarding his safety. Browne (2013) promoted the use of diaries as a means of documenting the challenges of fieldwork, noting how he found it meritorious.

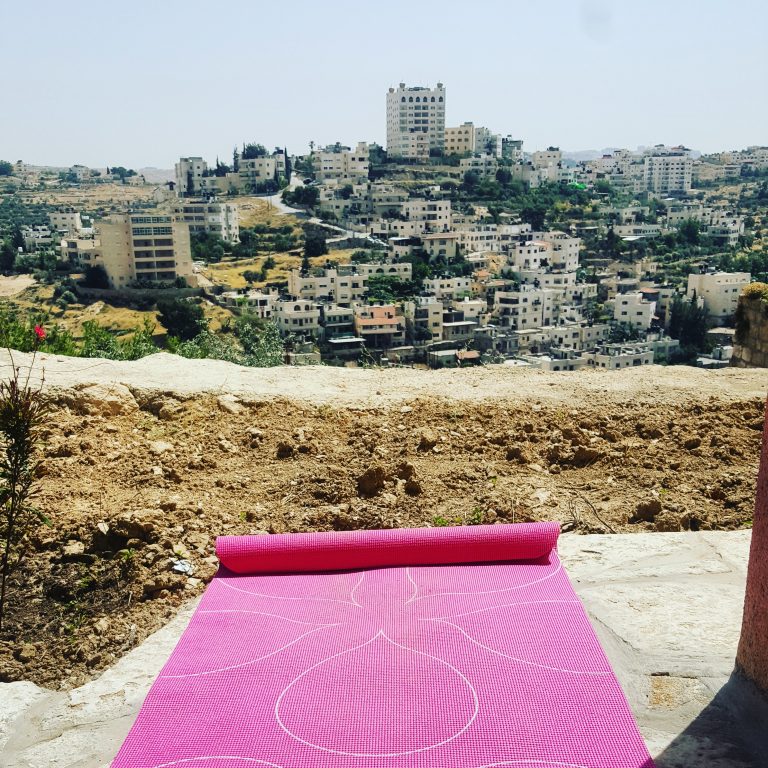

Whilst this is likely to be beneficial for many, for me writing does not represent a method of catharsis and instead, I have sought alternative means of coping with my frustration, stress, insecurity and apprehension. Acknowledging that some of these methods are not necessarily the most healthy, vices such as having a glass of wine in the evening have become an important part of the day. Similarly, I have turned to fiction as a form of release from the reality of daily researcher life here in the OPT and enrolled in the local gym, using exercise to expel frustrations. Yoga has become increasingly important, allowing me 15 minutes to reflect, or as some would call it become ‘mindful’ of the issues I faced that day, acknowledging them and allowing time to process. Yet perhaps, most interestingly, I have used Instagram to help me provide a photo journal of my time on fieldwork. This has allowed me to engage with those at home without having the pressure of ‘finding the right words’. It has allowed me to find beauty within daily life here, thereby helping me dissociate from the difficult personal narratives or the darker experiences of violence associated with the region.

Whilst these activities are not for everyone and may even be consider banal, for me their importance has taken on new significance in the context of fieldwork. Prior to leaving, I was given this piece of advice: ‘Be kind to yourself’. Initially, I did not understand the meaning behind this statement however it has quickly become my mantra to cope, acknowledging what I need in the immediate and trying to limit the expectations I placed upon myself within the context of the research. Rather than filling each day with a series of interviews, I have limited the number each day, ensuring some ‘me time’ to relax, unwind and reflect.

In writing this blog, I simply wish to acknowledge the challenges of fieldwork, something which is often hidden behind a guise of researcher pride. Heederik (2018) highlights the importance of preparing yourself as the researcher prior to fieldwork rather than simply the project itself. My hope therefore, is that in sharing some of my experiences, others may be better able to consider some of the personal challenges of fieldwork prior to entering the field. With that in mind, here are a few of the things I wish someone had told me prior to me embarking:

- Everything takes longer than you think – allow for this and expect the unexpected

- Fieldwork is an exhausting process – be aware of your physical and mental wellbeing and find ways to ‘switch off’

- Loneliness is difficult and can engender self doubt. Be aware of allowing vices to dominate

- Bearing witness is challenging but worthwhile, never be afraid to open up to friends and family

- Be kind to yourself!

First hand research and its ability to expand upon current knowledge within a field is incredibly worthwhile and rewarding. Personally, my fieldwork experience has sharpened my ideas, focus and understandings of the research at hand, with each interview proving another unique perspective to be considered. Most importantly however, fieldwork provides new ways of challenging yourself and the ability to learn and engage with others with different personal experiences. Despite its challenges, fieldwork is something that I would recommend to anyone.

References

Shaffir, W.B. and R.A. Stebbins. (eds). 1991. Experiencing Fieldwork: An Inside View of Qualitative Research. London: Sage.

Browne, B.C., (2013). Recording the personal: The benefits in maintaining research diaries for documenting the emotional and practical challenges of fieldwork in unfamiliar settings, International Journal of Qualitative Methods, Vol. 12, Issue 1, p420-435

Heederik, D. (2018). The challenges of doing fieldwork: when your academic skills are not enough, De Antropologen Beroepsvereniging, [Online], Available at: http://antropologen.nl/the-challenges-of-doing-fieldwork-when-your-academic-skills-are-not-enough/, Accessed 19th May 2018

0 Comments