Europe’s biggest climate disaster: Health impacts of the 2003 heatwave and the long-term implications of warmer summers

The blog has been written by Helen Jones, who is a first year student on the BSc International Disaster Management and Humanitarian Response. As part of her assessment on the module International Disaster Management, she was asked to write a blog post of a 1000 words that considers the short term and long term impact of a disaster of her choosing. Her submission for this assignment was judged to be amongst those of the highest calibre for the whole cohort.

British people love nothing more than talking about the weather. This may be surprising to those living in areas that suffer deadly hurricanes, decade-long droughts or temperatures that could freeze you to death, yet despite the odd storm and occasional flash floods, Britain has seemingly little to worry about… or does it? What if I were to tell you that the increasingly warm summers we hope for, have already been responsible for the deaths of tens of thousands of British and European citizens across the continent and warn of a greater climate catastrophe.

One of the top ten deadliest disasters to hit Europe was the heatwave that occurred between June and August 2003 – temperatures reached 20-30% higher than seasonal average and soured between 35-40°C2 – in Britain, temperatures surpassed the 100°F for the first time since records began. While many Europeans indulged in the hottest summer in 500 years, the heat proved fatal for tens of thousands of European citizens, as well as having both short and longer term social, environmental and economic impacts.

By focusing on the revised statistics and long-term analyses, that estimates 70,000 deaths were a direct result of the heatwave, I hope to shed light on the health impacts of the 2003 heatwave, why it was so deadly and whether or not similar events will become more common this century. Poor harvests, forest fires and water shortages were the most commonly reported impacts of the heatwave. In Portugal alone, 215,000 hectares of forest was destroyed, as fires broke-out and spread uncontrollably; furthermore, significant glacier-melt across the European Alps led to deadly rockfalls across Europe, all contributing factors to the eventual death toll across Europe; however, healthcare system failures across the continent was the primary cause of death amongst the elderly.

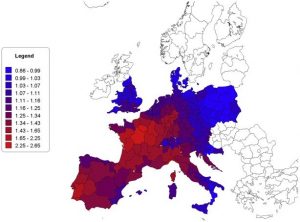

Figure 2: Standardized daily death frequencies (1 means equal to the median death number, 2 means twice the median death number) between 3 and 16 August 2003, in 16 European countries

By August 14th, 2003, French President Jacques Chirac acknowledged that 10,000 people may have died as a direct result of the heatwave following heavy criticism that the French government had acted slowly and insufficiently to the crisis. Chirac announced that “Many fragile people died alone in their homes… To avoid these tragedies in the future, our prevention, surveillance and alert system will be reviewed so as to ensure greater effectiveness”. At the time, France had the leading health care system globally, yet had failed to acknowledge climate events as ‘health risks’7. The death toll during the heat wave rose significantly for the elderly demographic, with mortality rates for those aged 75+ being 16.5% higher than average. Elderly are particularly at risk from heat-related illness and death as our bodies become less efficient at controlling body temperature. Many heat-related deaths were also due to environmental issues.

Future preparedness has been discussed across the continent; nevertheless, ‘thermal comfort’ building regulations and updates have still not been implemented by the British government, despite the recommendation of the CCC in 2015 after issues were raised by public health inquiries after the 2003 heatwave. The British government also published ‘The National Heatwave Plan’ in response to 2003, which aims to “provide guidance on how to respond and prepare for a heatwave” for health sectors and in doing so mitigate the impacts in the future; however, it only suggests planning to limit the effects of climate change, with no regard to limiting climate change itself. This is despite the Met Office who co-authored the plan previously stating that “Summers as hot as 2003 could happen every other year by the year 2050 as a result of climate change due to human activities”.

Figure 3: Artist’s depiction of global warming and climate change | Source: The Daily Conversation15

Scientists from the Met Office published separate research, in to the likelihood of similar heatwaves and concluded that extreme hot-weather events that would occur twice-a-century in the early 2000s, are now predicted to occur twice-a-decade. Using Optimal Fingerprinting and simulation analysis, they also found that human influence at least doubled the chances of these extreme hot weather events and that severe heatwaves would be commonplace in Europe by 20407; moreover, their findings “suggest the 2003 summer will be deemed an extremely cold event by the end of the century”. During the heatwave, Sir Crispin Tickell, a climate change expert warned of a clear and obvious trend, that the world is getting warmer and that human activity is most responsible for it. Furthermore, Daniel Mitchell, a professor at the University of Oxford ran thousands of tests with his colleagues on different climate scenarios, with and without the impacts of greenhouse gases, emitted by humans – the simulations showed that 70% of heat-related deaths in Paris, and 20% in London could be directly attributed to climate change.

In the last month, we have seen yet another alarming reminder that our climate is in turmoil. Whilst many of us enjoyed the 20°C heat in February, according to scientists, it represents a trend we are likely to see more of globally – evidencing that the 2003 heatwave is evidently not a one-off and is arguably a result of our changing climate. Going forward, it is about time our small-talk about the weather turned in to a more meaningful conversation. More importantly still, it is about time we take more responsibility for what is happening to our climate and what extreme weather events really mean regionally, nationally and globally, in order to take the vital and long-overdue action needed, to protect ourselves in the future.

0 Comments