Discrimination and Disasters: The experiences of women in the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami

The blog has been written by Mathilda Shannon, who is a first year student on the BSc International Disaster Management and Humanitarian Response. As part of her assessment on the module International Disaster Management, she was asked to write a blog post of a 1000 words that considers the short term and long term impact of a disaster of her choosing. Her submission for this assignment was judged to be amongst those of the highest calibre for the whole cohort.

When we think of disasters and how they impact the people living in the areas they strike, the factors we tend to consider are the magnitude or intensity of the disaster, how close the affected population is to the source of the disaster or perhaps, more recently, the level of economic development of the affected area. One factor that is very often overlooked is how other factors such as age or, specifically for the purpose of this blog post, gender may impact how seriously impacted a person is by a disaster.

The Indian Ocean Tsunami:

On Boxing Day 2004, a devastating tsunami, triggered by a category 9.0 earthquake, hit coastal areas of Indonesia, India, Sri Lanka and Thailand. Instantly, it was recognised that hundreds of thousands of people would have been killed; it was only later that the unequal distribution of men: women killed was identified. In Indonesia, the ratio of women: men killed in the tsunami was 3:1, while in the village of Pachaankup in India, only women died.

Banda Aceh, Sumatra, Indonesia.’ In Aceh, the ratio of male: female survivors was 3:1. Source: BBC News

These figures demonstrate that while the disaster itself may not discriminate with who it impacts, there must be multiple pre-existing factors that serve to make certain groups more vulnerable to a disaster such as this one. In this blog post, I will discuss two of these and how they could have led to such a gendered death toll and other short-term impacts.

Gender Roles:

In all societies, the capabilities of men and women are largely defined by gender roles. However, when a disaster hits, the skills you were or were not taught depending on your gender could save your life. In Indonesia, for example, it was considered taboo for a woman to know how to swim or climb trees, which made them significantly more likely to drown when the tsunami hit the shore as they did not possess the same life-saving skills as men. In addition, as-per another common gender role, many women would have been at home when the disaster struck, and this also increased their vulnerability, as they, (a), would have much less visual warning that the tsunami was approaching so lost time to react, (b) would most likely have been caring for dependents such as children and the elderly so would have lost time to escape the tsunami by collecting them, and (c), their ability to swim or combat the wave would have been restricted if they were holding onto children or elderly relatives, as you can see from the photo below.

In India, the division of labour was also according to gender roles. The dominant form of labour in coastal areas was fishing, and the different roles men and women played in this industry also increased women’s vulnerability to the tsunami, as the men would have been on the boats, and so the wave could have passed beneath them completely undetected. Meanwhile, at the time the tsunami hit, many women would have been waiting on the beaches to collect the produce on the men’s return to sell, so would have been extremely vulnerable.

Exclusion of women from disaster research:

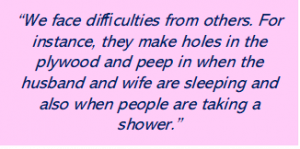

The gendered nature of disasters is not specific to this event. Yet despite this, the vulnerability of women is still neglected from government and aid organisations’ disaster preparedness plans. The significance of this is how it impacts women’s experiences after the disaster, in camps. For example, ignoring cultural practices that are specific to women, such as purdah (the practice of screening Muslim women from male strangers) meant many women did not seek medical attention, as they would not see a male doctor and female doctors were not often present in the camps. Also, the conditions in the camps were unsafe for women, with issues such as a lack of privacy in toilets and shelters, which meant the incidence of sexual assault was extremely high. Had more attention been paid to the needs of women by aid organisations when they were planning their responses to the disaster, this may not have been such an issue.

Long-term Impacts:

It has now been 14 years since the tsunami, which allows us to also see what some of the more longer-term impacts of such a gendered death toll have been. For example, discrimination against girls has increased, with child marriages becoming more common while families recover economically from the disaster. There has also been an increase in girls having to drop out of school to take over the role of their mothers who died in the tsunami. Other human rights violations against women have also increased, such as women being forced to reverse the process of desterilisation that many went through in order to replace children who died in the tsunami, an extremely traumatic practice. In general, the effect of the tsunami has been to increase gender inequality in the affected areas, as women have suffered a loss in education, economic security and personal security both in and outside the home. This leaves women vulnerable in exactly the same way they were in 2004, suggesting new strategies are needed.

Strategies for the future:

Some strategies for decreasing the vulnerability of women in this region have been proposed. For example, the work of grass-roots organisations such as the Ruhunu Rural Women’s Organization in India aims to improve the socio-cultural practices that made women vulnerable in 2004. For example, one of its strategies is a microfinancing operation, which allows women to deposit small amounts of money which would become available to them in an emergency situation, so they are less dependent on aid, governments and male relatives. It also gave grants to women to start small businesses after the tsunami, which is important as it encourages self-empowerment which can ease the psychological impacts of a disaster.

0 Comments