Creative, sensitive and grounded in diverse perspectives: Why we need inclusive climate change education

Catherine Walker, Kit Marie Rackley, and Nerida Jolley analyse how climate change education can address rather than exacerbate eco-anxiety.

How can climate change education address rather than exacerbate eco-anxiety, whilst also valuing and learning from diverse perspectives? Following a strong collective youth voice at COP26, climate and sustainability education have become more prominent on governments’ agendas. Soon after COP26, the Scottish Government announced plans to update and strengthen its Sustainability Action Plan, designed to implement its flagship Learning for Sustainability policy. Following suit in April 2022 the Department for Education (whose remit covers educational institutions in England) launched a revised ‘Sustainability and Climate Change strategy’. Among the initiatives in the strategy is a new GCSE qualification in Natural History to be introduced from 2025, which some teachers hope could be a focal point for teaching on climate change.

Similar policy and curricula updates have been seen around the world. Up until 2022, when version 9.0 of the Australian Curriculum was released, climate change was mentioned explicitly only four times. Now there are (according to one count) 32 references to climate change across a range of subject areas: civics and citizenship, geography, history, science, mathematics, technologies, and the arts. In launching a set of teaching resources to coincide with the 2020 ‘Our Atmosphere and Climate’ report, the New Zealand Ministry for the Environment explicitly linked the development of these resources to demands from young people. Notably, the resources prioritise the inclusion of mātauranga Māori [Māori knowledge] in teaching on climate, acknowledging the contribution of ‘centuries of observational data on the state of Aotearoa’s weather and climate’.

In updating curricula and policies, governments are catching up with concerns that have been crystallising in many young people’s hearts and minds – and, for a vocal minority of young people, through collective action – in recent years. As one Melbourne-based teacher shared in an interview with Catherine in 2021:

One of my favourite questions to ask kids is open-ended: what is the biggest environmental issue facing Australians at the moment? So, I ask kids that when I interview them when they go for leadership positions in the environment portfolio at the school and [over the last five years] it has changed away from more generic things about forest clearing and biodiversity loss, and no doubt the most common answer over the last five years has either been the Great Barrier Reef or climate change full stop.

The politics of climate change education – and the impacts on teachers and students

Knowledge about climate change – scientific and otherwise – is being generated and updated continuously. However, teachers and students commonly report ‘information overload’ and a sense of paralysis of where to start in responding. As a UK-based teaching advisor commented in an interview in 2021:

This is such a rapidly evolving [area] – there’s so much data and so much evidence and so much that teachers have got to get their heads around and actually they have to be confident in their subject knowledge as well, so it’s a really complex area.

Moreover, whilst the science on climate change is clear, there is ongoing uncertainty among teachers about how responses to climate change are to be framed. The UK Department for Education’s strategy for climate change and sustainability education explicitly states that teaching both the science and human-made causes of climate change is not a political issue (see section entitled ‘Political Impartiality’ within Action area 1: Climate education). However, despite research calling for urgent and deep-rooted social and economic reforms to tackle climate change, the strategy urges caution when addressing these necessary actions in the classroom. This can further erode teacher confidence to teach on climate change, and it can mean that students are left feeling disempowered.

For example, students interviewed for the Young People at a Crossroads (YPAC) project in 2021/22 said things like: ‘when it comes to the time where they [teachers] are actually going to tell us what we can do, they don’t usually have specific instructions’ (Zac, Melbourne) or ‘we are learning about the consequences, with a bit tacked on at the end about solar panels or wind turbines’ (Madeleine, Manchester).

So, to return to the opening question, how can climate change education address rather than exacerbate eco-anxiety, whilst also valuing and learning from diverse perspectives? And although climate change is often framed as a ‘controversial’ issue, how can we ensure that substantial weight is given to the perspectives of young people bolstered by intergenerational and intercultural conversations? After all, as one young researcher in the YPAC project pointed out, quoting the Native American saying, “We do not inherit the Earth from our ancestors; we borrow it from our children”.

Young People at a Crossroads

The recently completed Young People at a Crossroads (YPAC) project explored student and teacher experiences of climate change education in Manchester and Melbourne. This was part of broader research into intergenerational conversations about climate change in homes where, through their migration experience, family members have different exposures to lived experiences of climate and sustainability challenges.

Data collection for YPAC ran from June 2021 to June 2022 and involved 40 young people aged 14-18, 16 parents and grandparents, and 14 educators. The young people had all either migrated internationally or grown up with one more parent who had migrated internationally to Manchester or Melbourne. In addition to sharing their own perspectives in interviews and focus groups, young people were given training to interview parents and treated as ‘young researchers’ on the project.

Whilst acknowledging that all young people have important perspectives to share, YPAC researchers spoke to migrant-background young people and families both as a way of addressing gaps in research knowledge (as has been argued elsewhere, immigrants’ responses to climate and sustainability concerns are overlooked in social science research) and to learn from diverse families’ lived experiences. Here, we present three key findings about climate change education from the research.

Students want action-oriented teaching on climate change

Climate change is something that is going to affect us all and we need teachers to link our lessons to the kinds of things we are learning and skills that will be useful to solve the problems […] It’s not taking away from the negative consequences or making it seem less serious but talking about small positives would make the future a bit less daunting.

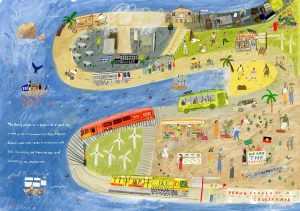

The book cover of the creative project book of the YPAC project

A growing number of studies report on the emotional impacts for young people of being surrounded by talk about climate change. One of the largest studies, carried out with 10,000 16-25-year-olds from ten countries found that 59% of participants were ‘very or extremely worried about climate change’, with participants also reporting high incidences of sadness, powerlessness or guilt. All of these emotions were expressed by YPAC young researchers and are explored in the creative book we have produced from the project. However, young researchers’ responses also show that taking action on climate change can soften anxieties. Indeed, for participants, taking action was often spoken of as a way to combat despair, as expressed in the quote above from a young researcher in Manchester.

Climate change education must recognise contextual differences and inequalities

[In Pakistan], even though it is very hot, lots of people don’t have air conditioning, we often can’t use it because of power cuts or even if we have it, we don’t want to because we know the environmental impact it will have going into the future […] in high income countries people might take their power resources for granted, but these resources are finite.

‘Climate justice’, referring to how those at greatest risk are often the smallest contributors to anthropogenic climate change, is a term that has increasingly been used by activists and is beginning to be explored by educational researchers. The YPAC team did not set out to speak (only) to young people who identified as climate activists, and in doing so the project sought to expand popular ideas of how young people understand climate justice. Despite the initial unfamiliarity of the term ‘climate justice’ to most of the young people taking part, they found inspiration in the term. Some young researchers felt this resonated with their understanding of how climate change was affecting countries differently, including the countries where their parents had migrated from and, in some cases (as in the case of the Pakistani-born young researcher who shared the quote above), where they were born. They wanted climate education to better reflect the regional differences and inequalities that climate change draws attention to and runs the risk of exacerbating.

On the ground stories can build empathy and engagement

Like my Dad was saying, the people in his village [in Nigeria] kind of just saw the natural hazards as something that just happens. They weren’t necessarily like ‘this is climate change [and] we need to try and stop it’. So maybe it would be good to look more at why the people in the communities think things happen.

Researchers working with teachers and learners have called in recent years for more creative and participatory ways of engaging students in learning about climate change. This was a key finding of a systematic review into climate change education. A proposed ‘creative turn’ in climate change education fits with perspectives shared by young researchers in both Manchester and Melbourne for YPAC, who felt that on the ground stories could bring climate change to life and offer alternative perspectives to taken-for-granted ways of thinking about climate change. Rebecca, who shared the quote above, did so after interviewing her father, who spoke of changes he had observed in return visits to the village where he grew up in Nigeria. Rebecca reflected that greater consideration of why those most affected by environmental hazards thought these were happening could enrich her own and other students’ understandings of the differential effects of climate change.

One of Maisy Summer’s beautiful images for the YPAC creative book

Creative, sensitive and diversely informed: Moving forward with climate change education

Findings from the YPAC study show in practical terms how the diverse perspectives of just a small group of young people and their families can offer prompts for learning that work across various school subjects and can go beyond schools into wider communities. Although we worked with a relatively small group of people, there is great potential to scale up research with learners and teachers alike. More research in this area can help societies to treat opportunities to learn from different perspectives – across generations, country contexts and cultural backgrounds – as among the greatest resources we have to mitigate and adapt to living with climate change.

To find out more about the YPAC project, please visit our website. A key output of the research is a creative book that presents thematic summaries from the project and original reflections from young people who interviewed their parents for the research, each illustrated by the Manchester-based artist Maisy Summer. This can be downloaded from the ‘Project Resources’ page.

About the Authors

Catherine Walker (she/her) is a Research Associate at the Sustainable Consumption Institute, University of Manchester and an Honorary Researcher in the School of Geography, Earth and Atmospheric Sciences at the University of Melbourne. Her research focuses on the environmental knowledge, concerns and agency of young people through cross-cultural perspectives. She is the Principal Investigator on Young People at a Crossroads.

Kit Marie Rackley (they/she) is a climate science communicator and award-winning ex high-school Geography teacher in the UK. Much of their work revolves around the climate crisis, focusing around framing it as a school safeguarding issue. Kit Marie runs an educational resource blog at Geogramblings.com, and is host and producer of the Coffee & Geography podcast.

Nerida Jolley (she/her) lives and works on the unceded lands of the Wurundjeri people. Previously a passionate primary school teacher who at all opportunities nurtured a sense of wonder and awe of the natural world in her students; she now works at Environment Education Victoria. Outside of paid work, Nerida is an active community member and climate activist, with a focus on relocalisation, creating a more resilient and empowered community, and participatory democracy.

0 Comments