“What is a good climate change society?” SCI Annual Lecture by Harriet Bulkeley

Harriet Bulkeley discussed the processes, practices, and politics of nature-based solutions (NBS) in addressing issues within urban environments.

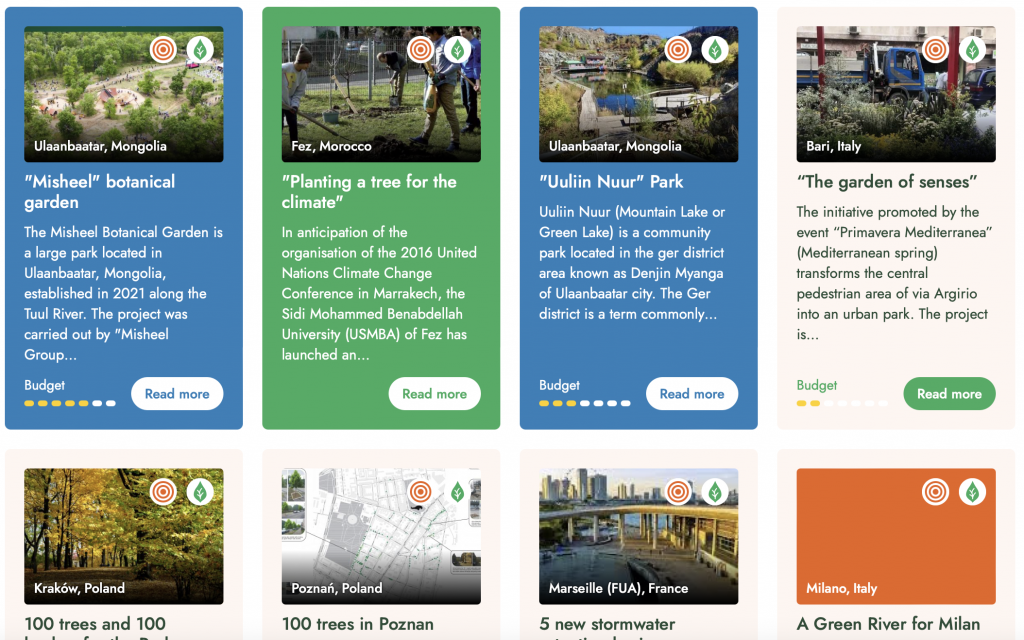

Featured image: Screenshot from The Urban Nature Atlas website

On December 3rd, Harriet Bulkeley delivered the Sustainable Consumption Institute’s annual lecture, titled “Governing with Nature: towards climate and social justice?” Drawing from her extensive research in climate change, nature, energy and urban sustainability, as well as her experience in interdisciplinary projects across the social and natural sciences, Bulkeley explored the transformative potential of nature-based solutions (NBS) in addressing urban environmental challenges.

Central to this discussion is the framing of NBS. Bulkeley began by questioning how nature has been framed as a solution to urban challenges and highlighted how introducing NBS into urban planning requires a shift in thinking and practice—a move toward governing with nature.

“What is under radar is should be a policy”

A key aspect of Bulkeley’s lecture was the exploration of how NBS transforms urban governance. To the delight of the audience, the variety of ways to govern with nature was reflected in nature-focused language. For instance, Naturescapes as a means to connect neighbouring areas into a network through greenways. Urban green spaces are being integrated into everyday environments, such as routes to schools, rather than just isolated parks. Naturvation: shifting perceptions of nature from a static “asset” to an active, participatory space. Urban farming initiatives are being leveraged to address food security (instead of covering the areas with trees as a standard way of approaching green spaces in cities) and enhance climate resilience, such as cooling cities through water features. Bulkeley noted that through her experience much of this transformation is occurring at the ground level, driven by local practices rather than top-down policies.

These aspects provoke the most audience response as the questions revolve around the prospects of mobilizing citizens to support NBS initiatives, focusing on how to effectively communicate these solutions at a grassroots level. Bulkeley noted that while the concept of working with nature was widely accepted, disagreements emerged when discussing tangible solutions, such as reducing parking spaces to create greener areas. Additionally, the discussion underscored the potential of NBS as publicly funded projects. For example, Newcastle, which has experienced a 90% cut in its parks budget, now relies on NHS public health funds to maintain parks as public health assets. This approach reflects a calculated investment aimed at mitigating future risks and serves as an example of the financial logic underpinning NBS projects.

Nature-Based vs. Naturally Good Solutions

Bulkeley addresses the tendency to equate NBS with inherently “good” solutions, emphasizing that their rise coincides with a broader understanding of climate change as a systemic issue rather than a discrete technical problem. The growing popularity of net-zero targets and carbon offset markets further illustrates how NBS are increasingly seen as integral to sustainable urban futures.

Paradoxically enough, the implementation of NBS often diverges from strictly environmental goals. Bulkeley referenced findings from the Urban Nature Atlas, a project she co-led, which catalogues over 10,000 NBS projects across 100 cities. The data revealed that only 14% of these initiatives focus solely on environmental issues, while 80% address social challenges and 40% tackle economic concerns. Importantly, they are frequently employed to address broader urban challenges—sometimes without fully articulating their broader systemic impacts.

“Is it a useful solution to bring nature and climate change together?”

During the multidisciplinary panel discussion following the lecture chaired by Mat Paterson (SCI/SoSS), with panellists Charis Enns (Global Development Institute), Mike Hodson (SCI/AMBS) and Carly McLachlan (Tyndall Centre), the conversation centred on the political implications of governing with nature and the implementation of NBS. One key thesis explored was that not all parts of nature are equally valued or desired, often leading to the creation of “fake nature” solutions to the climate and biodiversity crises. This approach fails to foster functional ecosystems and raises concerns about inequality, as highlighted by Enns. Additionally, the political possibilities and multiplicities inherent in NBS were discussed, prompting Hodson to question where the experimentation ends in urban governance. McLachlan added a perspective of policy making, questioning whether integrating nature and climate change in policy making is always beneficial, given that funding for such a solution is often restrictive and prescriptive.

Panel discussion chaired by Mat Paterson (SCI/SoSS), with lecturer Harriet Bulkeley (Deputy Executive Dean (Research) for the Faculty of Social Sciences and Health and Professor in the Department of Geography, Durham University, and Professor at the Copernicus Institute, Utrecht University), panellists Charis Enns (Global Development Institute), Mike Hodson (SCI/AMBS), and Carly McLachlan (Tyndall Centre).

In her response, Harriet emphasised the diverse ways we coexist with nature—whether it is perceived as fake or authentic, small-scale or expansive. She noted that urban ecosystems are inherently hybrid and multifaceted. The ability to define nature, she argued, is influenced by different social groups. NBS, while lacking a singular political orientation, carries progressive potential. Mapping and evaluating various NBS could provide a foundation for understanding their effectiveness and impact. Harriet also pointed out that experimentation with NBS is often driven by political and economic interests. For example, in the late 2000s, investment markets sought new opportunities, catalyzing urban development. Similarly, the pursuit of net-zero targets has spurred the rise of the “nature tech” community, which leverages technology to address challenges like biodiversity loss and climate change.

On a cultural level, Harriet raised the question of what it means to be “good”—whether as a city or as a society. She suggested that the modernist notion of goodness is outdated, and the search for a new understanding of a good climate-change society is ongoing. She also cautioned against positioning NBS solely as new or novel solutions, highlighting that not all NBS are entirely new. Urban ecologies are hybrid systems targeting various objectives, from addressing climate change to enhancing safety, inviting reflection on how we live with nature in our cities.

In an informal discussion after the talk, the issue of framing reappeared. One participant remarked, “Some groups, like right-wing christians might have considered fossil fuels as NBS because they originate from nature.” Framing indeed plays a crucial role in mobilising people around

0 Comments