Hidden infrastructures of decarbonisation

Matthew Paterson and Charlotte Weatherill discuss hidden infrastructures that exist as barriers to replacing flights with train travel.

As many of us start to travel again more for work after a couple of years of not doing so, and as the climate crisis continues to unfold further, limiting flying has become even more urgent. For those of us in academia, this is particularly so since air travel accounts for huge portions of overall carbon emissions for academic institutions and is widely recognised as a key issue in the sector.

We might think that the issues here are simple – cost and time. But our recent experience with international train travel suggests that there are also important hidden infrastructures that exist as barriers to replacing flights with train travel.

Much of the infrastructure for pursuing a low or zero carbon world is obvious – just to take the transport example, we need bike lanes to encourage more people to cycle, EV charging stations to eliminate the internal combustion engine, adequate train service to reduce both long distance car travel and aviation.

But there is also hidden infrastructure, which is only revealed as attempts are made to travel sustainably. This is an attempt to sketch that infrastructure on the basis of one such attempted journey which was ultimately successful but inordinately difficult.

As part of an ‘internationalisation’ initiative, a group of climate researchers from the University of Manchester were invited to a workshop at Stockholm University. Not wanting to fly, some of us decided to take the train. We knew it could work – our colleague Kevin Anderson has been travelling to nearby Uppsala by train several times a year from Manchester for a while. And the European rail system is really generally very good. We also had funding that would cover the higher cost of the trip. It seemed possible. So what made it difficult?

Hidden infrastructure #1: travel booking systems that favour flying

The University of Manchester requires all bookings to be made through Key Travel, an external travel agency used by many UK universities. This institutional requirement leaves you in the hands of hidden infrastructure number 1: travel agencies need to know how low carbon travel works and have systems to enable it.

“We make travel simple, cost-effective, safe and sustainable for people who travel to do good”

Despite their slogan “We make travel simple, cost-effective, safe and sustainable for people who travel to do good”, Key Travel did not really have the expertise to book trains outside the UK. Early on in the process they asserted they could not book European trains for us, something they then walked back on. But they were manifestly lacking in capacity to do this efficiently.

The whole process was clearly a monumental learning-by-doing process for the two agents involved. They knew nothing about European trains and had not been trained in booking them. They struggled (heroically to be fair) to work out how to think through the logistics of travelling from Manchester to Stockholm – what the best route was, how to match up each leg of the journey, how much buffer to allow between each leg, where the best break for an overnight hotel is, and so on.

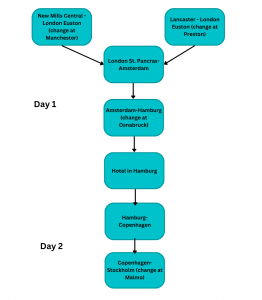

Illustration of the journey to Stockholm (return journey by train not pictured)

Overall, it took them over six weeks to work that out, involving very significant amounts of time and stress by us and university administrators to enable it (much more than if we’d done the bookings ourselves). There was a very tense moment five days before we were to travel when they said they could find no tickets for the last leg (Copenhagen to Stockholm) and it looked like they couldn’t do it. Their reaction to this was telling:

“Does this mean we can’t go?”

“Not unless you fly.”

Having cancelled the whole trip, they then managed to find some tickets overnight. The key lesson here is that travel booking systems need to have the skills and capacity to book train travel. This leads us to:

Hidden infrastructure #2: (dis)integrated ticketing

Stockholm central station arrivals hall.

The second piece of hidden infrastructure is integrated ticketing. All these tickets were running on different train systems (UK rail, Eurostar, Deutsche Bahn, SJ). There are integrated search sites like raileurope.com but purchasing tickets across all is not possible.

This intensifies the logistical difficulties for the travel agent, as they have to work out all the buffer time you need for each journey. And they can’t buy all tickets at once, so they have to hold each ticket (and hotel room) until they know they can book the whole journey.

And for the traveller, it entails the significant risk that if you miss a connection for a ticket on a specific train, there is no guarantee the train company will let you use the ticket on a later train. Even more, if you miss a train meaning, you cannot make the destination for the end of the day, your hotel booking is void and the next day gets completely messed up.

As shown above, the complexity of the trip we took is undeniable. However, if we had been able to book a simple London – Stockholm ticket, and then worked out the itinerary ourselves, the whole thing would have been much simpler.

This itinerary does also show that this was a 78-hour round trip made in a week. The costs of choosing train travel are not just monetary, but also in time. With the expectation that travelling to Europe can be done in a few hours, making the argument for a week-long trip is difficult.

Making sustainable travel normal

Alongside these infrastructural barriers, and enabling them, are the norms about travel, cost, and time, in university institutions (and many other workplaces also). Universities encourage, even require, academics to travel to conferences. This has particularly strong effects in structuring incentives for PhD students and postdoctoral fellows.

Junior colleagues are thus being trained to fly, and to see the travel itself as wasted or unimportant time. What if instead, as Laura Horn has recently discussed, trips were assumed to be taken by train, and this time and cost was written into the norms of attending a conference?

Travelling by train should be normal. Even over quite long distances. It should be cheap, well organised, easy to book, and use. The infrastructures that enable such journeys should be as well established as those that enable flying, if not more so. For this change to happen, the institutions that generate demands for this travel need to pay attention to these barriers that are being placed in our way, and create infrastructures and norms to make low carbon options more tenable.

0 Comments

Trackbacks/Pingbacks