Anti-Net Zero Populism and the future of British climate policy

Matthew Paterson, Stanley Wilshire, and Paul Tobin discuss the types of ANZP rhetoric and important lessons to learn from its (modest) successes.

In the last couple of months, the Conservative government has clearly made a decision to turn climate policy into a ‘wedge’ issue: rather than present itself as supportive of ambitious climate action and fight with Labour as to who is best placed to meet that, it has started to attack aspects of its own climate policy in order to distinguish itself clearly from Labour. The Uxbridge byelection in July was used as a testing ground to see if such a strategy might work, and they seem to have learned that it can. Since then, Sunak has announced reviews of both Ultra Low Emissions Zones and Low Traffic Neighbourhoods, and sought to frame Labour as ‘anti-motorist’.

These recent developments have been discussed in various ways elsewhere (see e.g. here regarding Prime Minister Rishi Sunak’s climate backlash, and here on how recent election losses for the Conservatives are forcing a strategic rethink). We provide the context to these developments through a recent journal article on right-wing populism against climate action. Our new, free-to-read article analyses the emergence of an important strand of Conservative political organising in recent years, around an explicit strategy of what we call Anti Net Zero Populism, or ANZP.

Elements of ANZP have occasionally surfaced in British politics, but opposition to climate action has been largely marginal for much of the period that climate change has been on the political agenda. But since the late 2010s, and especially with the establishment of the Net Zero Scrutiny Group (NZSG) of Conservative MPs, led by Steve Baker and Craig Mackinlay, attacks on climate action within the Conservative Party, and beyond it on the populist right, have become bolder and more widespread.

We wanted to analyse the nature of this mobilisation. We focused particularly on the types of rhetoric they use to undermine climate policy, to examine the potential for such narratives to lead to the rolling back, or dismantling, of existing climate policies. We found these ANZP discourses work at two levels.

On the one hand, ANZP actors attack net zero in itself. Perhaps helped by the technocratic nature of this framing of climate policy, established by Theresa May in 2019, ANZP voices argued that net zero was a strategy proposed and implemented by unelected and incompetent bureaucratic elites, imposed on an unwilling people, with potentially disastrous results. Steve Baker MP wrote, for example, that ‘Net Zero will mean quivering under duvets in the dark on windless winter nights’, while Craig Mackinlay MP sought to delegitimise the Climate Change Committee by saying it deliberately and radically underestimates the costs of achieving net zero. Notably, they almost entirely avoid language that denies the existence of climate change.

On the other hand, these attacks on the net zero goal have been supplemented by attacks on particular elements in climate policy; policies that were created under Conservative government. The most important of these issues for ANZP actors have been:

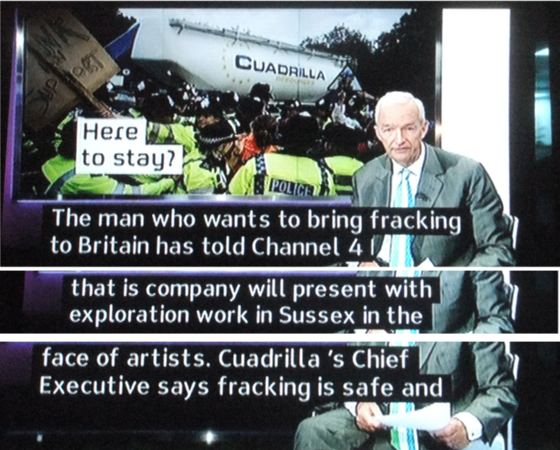

• The moratorium on fracking in the UK

• Policies promoting a shift to heat pumps instead of gas boilers

• Policies generally promoting renewable energy

• Policy support for Electric Vehicles (EVs)

• The petrol and diesel motor vehicle ban

• Low Traffic Neighbourhoods (LTNs)

The strategies for attacking each of these vary, but do so in a way that is revealing. While the rhetoric is generally populist – framing climate action as imposed by an out-of-touch and authoritarian elite on an unwilling people – it is not necessarily always popular.

Indeed, the most prominent target for ANZP actors has been the fracking moratorium. This moratorium is in fact highly popular amongst the public. The attacks by ANZP voices on a widely popular policy shows us that the support for oil and gas interests is at least as important for the NZSG and its allies as any support for a beleaguered public.

Meanwhile, the populist rhetoric has potentially more traction regarding heat pumps, EVs, and the petrol/diesel ban. The first of these, heat pumps, are, according to Richard Tice of the Reform Party (previously UKIP/Brexit Party), a ‘wasteful, expensive & not the solution, yet Westminster wants us all to have them. Out of touch, net zero madness. The people know it too,’ while Steve Baker argued it was ‘Soviet-style production planning’.

The petrol and diesel ban extends the libertarian strain in the populist rhetoric further, often mixed with an assertion of concern for those on low incomes. The ban is variously ‘dictatorship’, and an ‘attack on the working class … only the rich will have cars’.

The targeting of specific targets is largely opportunistic. ANZP actors seek to target actors that will enable them to roll back climate action in the most effective way. However, for the time period we examined in our article (2021-2022), their opportunism was not always successful. ANZPs attempted, unsuccessfully, to leverage the spike in gas prices following the Russian invasion of Ukraine to build support for fracking. In contrast, during 2021 and 2022 they made very little of Low Traffic Neighbourhoods, which appeared mostly in articles about the NZSG and its allies but not in their own statements, despite the existence of movements protesting particular LTN initiatives.

We were surprised that there was so little made of LTNs by anti-net zero populists during 2021-2022. Since then, we have seen an increase of interest by them in LTNs. The conspiracist groups mobilising against 15-minute cities in early 2023 fed into this opposition, and while conspiracies were primarily supported by fringe groups, they tapped into the populist potential of opposing LTNs. Since then, ANZP actors such as Craig Mackinlay have joined the anti-LTN bandwagon.

Opposition to LTNs has clearly fed into Conservative government strategy under Sunak. It has provided both pressure within the Conservative Party, but also an alternative approach to climate policy which now appears to its leadership as worth pursuing. To be sure, the government is also desperate, having been over 15 percentage points behind in the polls since October 2022, and seemingly without clear issues it can use to claw back this position. In this context, seeing the effectiveness of the ANZP rhetoric, at least in some contexts, appears to it as a necessary tactic.

But there are important lessons to learn from the (modest) successes of ANZP. The UK government has been able to deliver substantial emission cuts so far through simple policy interventions that have had limited impacts on people’s lives – a coal phaseout, pursuit (since around 2008 at least) of renewable energy supply, and one or two other specific policies. However, the next stage of climate action – electrification of transport and home heating – require more intrusive changes and, in the UK’s economic policy regime of regressive taxation and excessive fiscal discipline, depend on imposing costs on citizens. Despite the potential for climate action to provide improvements to quality of life, such policies are therefore also exposed to the attacks of right-wing populists who have plenty of cultural and economic grievances to mobilise to boost their agenda of climate delay. To counter these challenges, future climate policy must integrate progressive redistribution as well as broader concerns of social and economic justice.

0 Comments