The other side of the fence: Consumption, activism, and the Owens Park tower occupation

Anna-Maria Köhnke explores the role universities and students play in the climate movement.

What links the University of Manchester’s library and the most notorious student halls in town, except for the high density of flared trousers and pastel coloured hair? Correct – countless Stagecoach buses, going up and down the Wilmslow Road bus corridor, which is allegedly the busiest bus route in Europe. With Stagecoach drivers going on strike in neighbouring Merseyside throughout July, it is worth taking a look at worker and consumer action, and the role universities and students play in it. The strike is part of a wider wave of industrial action across the UK, raising awareness of the effects that record high inflation has on consumers. While industrial action has been all over the news in recent weeks and months, other forms of protest have received less attention – partly because their successes are less visible to the public eye.

When students started occupying the Owens Park Tower in Fallowfield on 12 November 2020, an empty residential building, there was a fair amount of scepticism among observers. Some questioned the impact that occupying an unused building would have on the university; others were certain that an early release clause from tenancy contracts would be the maximum of what students could achieve through their protests. Barely anyone would have expected the rent strike and its associated occupation to result in a rebate of 30% of rent, which amounts to £4m.

A closer look into the motives behind university rent strikes quickly reveals that the protests are about more than just the price students pay for housing, as stated on the website of the national campaign: “[…] although the short term goal may be about getting a few quid in a student’s pocket, the end goal is the resistance to marketisation of both universities and, more importantly for the working classes, housing.” What, if anything, is to be learnt from Fallowfield’s rent strike and occupation regarding the connection between consumption, higher education, and sustainable living conditions?

Occupations: protesting commodification

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought attention to problems which are by no means new to most people involved in higher education. High rents for inadequate buildings, “often plagued by damp and rodents”, have been bothering students for years. Yet, the pandemic seems to have created momentum for tenants around the country to take action. The rent strike movement is one example of how consumers begin to fight back against the conditions of consumption, which – contrary to assumptions from mainstream economic models – are experienced as entirely out of control from consumers’ perspective.

An apartment block with graffiti.

Occupations and rent strikes have a long history as mechanisms of collective consumer action. In particular, occupying and squatting in empty buildings has been a means of satisfying housing needs that are unsatisfied by the regular housing system, which is dominated by scarcity and insecurity. This has often occurred in buildings that others would not deem suitable for living in order to strengthen the protest nature of the occupation; Vasudevan mentions “living in ruins” in East Berlin in the 1980s as a movement that shaped Berlin’s activism landscape for future decades.

However, occupations have usually been more than just the appropriation of empty living spaces; they have inherently political elements. People participating in occupations protest against being forced into the ‘consumer role’ in areas which they think are unrightfully commodified. This involves areas beyond the main aim of the occupation. Student rent strikers protest the commodification of higher education more widely, as their statements reveal. In other cases, like the occupation of the John Owens building in 2019, students protested the commodification of the environment by urging the University of Manchester to divest from fossil fuels.

The role of the ‘Tower’

An apartment block.

Causing disruption by occupying crucial university buildings is one possible way to gain attention. However, as the occupation of Owens Park Tower demonstrates, it is not the only way. The Tower has been a symbol for Manchester student culture across several generations. No matter from which direction you come, from the airport or from Piccadilly station, spotting the tower is the first sign that you have made it back to Fallowfield, no matter where you come from and who you are. This is not despite the low quality of the accommodation, but because of it – it is symbolic for a living standard that somewhat unites people despite their differences. Similar to “living in ruins”, part of its power as a location for protest stems from the fact that most people at whom the protest is targeted would never consider staying there for a night, let alone for almost two weeks.

Awareness for their accommodation’s health and safety issues increased among students after the Grenfell Tower fire, an event that politicised students against the housing crisis that affects large parts of society beyond the student population. Occupying the tower is therefore not about causing disruption to processes that matter to the university leadership, it is about demonstrating that these demands stand in the tradition of complaints that students have been voicing for years or even decades, and that matter not just to students but to everyone entering the housing market as a consumer.

Monopoly landlords and ‘consumption as purchase’

The UK’s most successful rent strike took place in Glasgow in 1915. Joubert and Hodkinson argue that today’s housing market is too different from the situation in the early 20th century, which was shaped by monopoly landlordism, and that traditional rent strikes today cannot be as effective as they were back then. This hints at a possible reason for why Fallowfield’s rent strike during the pandemic was extraordinarily successful: for first year halls of residence, the position the university is in has similarities to that of a monopoly landlord. A large percentage of new students move into university-owned accommodation for numerous reasons, partly because it is considered vital for the ‘experience’, partly because of the difficulty of finding alternatives in a new city, partly because of the hope of receiving additional support during the first months of university. These incentives result in other options for consumer action, like a boycott or a “buycott”, being unavailable or unfeasible to the consumer-student, who might even be threatened with academic repercussions for disobedience. On the other hand, this particular market structure means that tenants hold a considerable amount of power themselves – students withheld over £300,000 in rent during the strike.

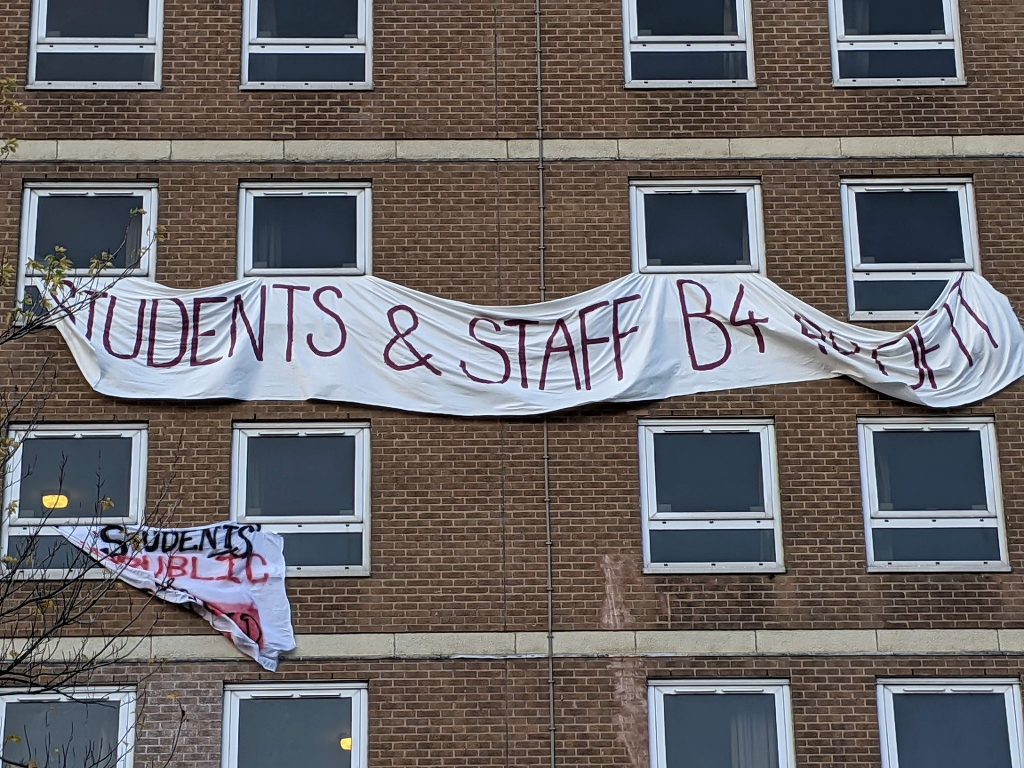

A protest banner on a building.

The university’s first offer, equivalent to a 5% reduction in rent, was met with further protests from students; they explained that this amount would merely account for a time period of two weeks, which, according to government advice, they would not spend in university halls anyway. At the heart of this lies a protest against the notion ‘consumption as purchase’ rather than ‘consumption as use’ – the consumer of accommodation, as advocated by other occupations throughout history with slogans like “houses to those who live in them”, ought to be understood as a user of accommodation, not merely as a purchaser.

Occupations fundamentally challenge the idea that ‘consumption’ is synonymous with ‘commodification’ or ‘purchase’. They draw attention to how consumer rights and duties are framed as purchaser rights and duties, rather than user rights and duties. Consequently, they pull the ‘using’ side of consumption out of the solely private realm and back into public debate, which usually assumes consumption as strictly contract-regulated ‘purchasing’.

Consumer action – a form of consumption work?

A theoretical concept that challenges the notion of ‘consumption as purchase’ is Wheeler and Glucksmann’s ‘consumption work’, which describes the work “necessary for the purchase, use, re-use and disposal of consumption goods and services”. Wheeler and Glucksmann analyse household recycling as a form of work necessary to maintain the conditions for future consumption. A possible interpretation of consumer action, such as protest against current conditions of consumption, would be seeing it as a form of consumption work. In order to maintain consumption (of accommodation and ultimately other consumption goods, since housing is often a prerequisite for other forms of consumption), tenants invest time and effort into raising awareness for their inability to cope with current consumption conditions in the long run. This could be a starting point for broader recognition of types of activism as work. Consider the example of industrial action – a strike, the temporary refusal to generate profit for an employer, would then not be seen as a withdrawal from the ‘realm of work’ but instead as labour towards the organisation of work itself.

German Green Party politician Claudia Roth remembers the last performance of German squat scene band Ton Steine Scherben at a Green Party campaign rally in 1985. Roth, who spent several years as the band’s manager, emphasises how de-alienated work and private life were tied closely together in the band’s daily routine. The occupation of Owens Park Tower, in line with previous protests against commodification, serves as an example of consumer action that spans across various socioeconomic topics out of necessity – housing, inequality, and environmental concerns have always been viewed as interrelated by the squatting movement. Squatting as a protest form has a long history of being belittled or ridiculed by those at whom the protest was directed. Yet, the radical origins of today’s environmentalist decisionmakers demonstrate that consumption work appears to be a promising lens towards a better understanding of the fight for more sustainable living conditions.

It is yet unclear what the long-term effects of the public transport dispute will be on the student community. In 2017, the price for a single ride on the Magic Bus from Owens Park to lecture theatres was £1.00 – now, with the UK government only granting half the funds Greater Manchester applied for to reform its transport system, this could increase from the current fare of £1.50 to £2.00. This would be a 100% price increase for a service that many students depend on daily within less than five years – given the recent history of Manchester’s students protesting for their rights, there might be more action to come in the near future.

0 Comments