We all have to become better economists

Caroline Cornier reflects on the International Conference on Land Grabbing 2024 in Bogotá, Colombia.

From the 19th to the 21st of March 2024, Colombia’s prestigious Los Andes University in Bogotá, Colombia hosted the International Conference on Land Grabbing. The country’s first leftist, land reform-pushing government was happy to be the host. The Land Deal Politics Initiative (LDPI) first convened this conference in 2011, against the background of the financial crisis’ repercussions in the food, land and energy sectors. LDPI is supported collectively by the Institute of Development Studies (IDS), Cornell University, City University of New York, the International Institute of Social Studies (ISS) in The Hague, the Institute for Poverty, Land and Agrarian Studies (PLAAS) at the University of the Western Cape and the Transnational Institute in Amsterdam. More than 10 years later, at a time when the world faces enhanced social, political and environmental crises, the conference, co-organised by the Journal of Peasant Studies, World Development, Antipode, Globalizations, and Análisis Político, aimed to investigate new evolutions within land grabbing.

What’s new under critical research’s sun?

To this end, eminent scholars such as Marc Edelman from City University New York and Colombia’s former minister of Energy and Mining and editor of Geoforum Irene Vélez-Torres, now Professor at the Universidad del Valle, discussed land grabbing’s links with financialisation, geopolitics and climate change. Hence, they touched upon decade old debates on land grabbing’s relationship with capitalism and the compatibility of agro-ecology and population growth. It was in this context that Ruth Hall, from the University of Western Cape, declared that given the all-encompassing nature of today’s financial sector adequately tackling land grabbing demanded to become ‘better economists’. In particular, PhD students and younger scholars met this demand by contributing fresh perspectives on the new prominence of finance in rural development in the Global North and China. For example, Alex Heffron from Lancaster University examined new, financialised enclosures of Welsh sheep farms for carbon credit procuring timber production. Katherine Aske, from the University of British Columbia, highlighted the increasing distress and isolation of Canadian grain farmers given capital needs and over-indebtedness. Madeleine Fairbairn, from the University of California, Santa Cruz (and her random flight buddy who she referred to in her intervention), showcased the financialisation of American farmland, which is now available for purchase based on crowdfunding schemes open to anyone. Other extremely interesting perspectives came from China. Yunan Xu and Ye Jingzhong from China Agricultural University, discussed China’s actual role as frequently asserted overseas land grabber and reminded us of the country’s long achieved full scale land reform, the supposed ideal among Agrarian studies scholars and much of the Latin American left.

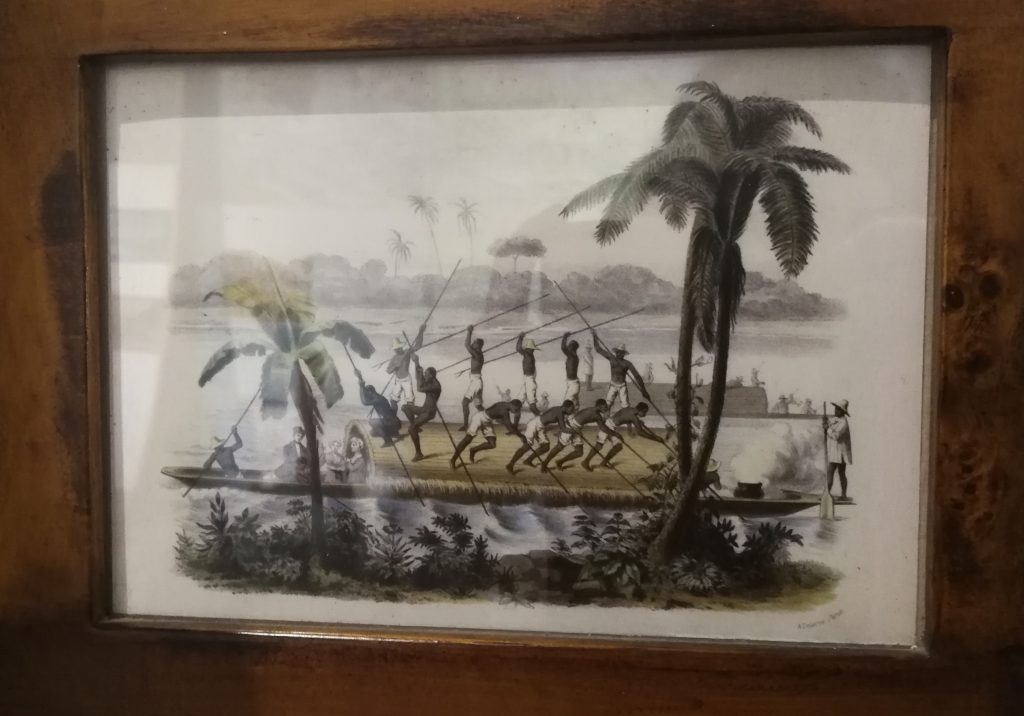

Spanish colonialists crossing Colombia’s river Magdalena with African slaves transporting wood and tabacco to the country’s biggest port in Cartagena. It can be found in the River Magadelena Museum in Honda, Colombia.

The limitations of political consensus

In terms of participants, the conference organisers did an excellent job in making the event as inclusive as possible for local and regional activists and Global South scholars by funding 27 participants’ travel expenses. No conference fees were charged and there was simultaneous translation in English, Spanish and French throughout the conference. As a result, participation from the Global South, especially from Colombia itself, including from activists, politicians and scholars was very high.

Despite the organisers’ best efforts, the conference also highlighted, however, how difficult it is to ensure real dialogue emerges between activists and academics. Activists from Colombia and the Global South generally made important declarations about the hypocrisy of Western development aid and ongoing environmental destruction. Their consistent calls for solutions rather than theory were received with applause but were not addressed as most academic debates focused on the theorisation of land grabbing.

In this context, Ruth Hall’s call for more economic analysis of land grabbing and Madeleine Fairbairn’s mention of the colonial legacies of many land grabbing examples stood out as important, highlighting how the literature on land grabbing could be advanced. There remains a consistent danger that discussions around land grabbing don’t advance beyond identifying neoliberalism and Western capital as the exclusive drivers of land grabbing without considering broader political economy questions. While the conference highlighted the importance of solidarity with social movements, more productive discussions about distributional political economy questions were less easy to find. In fact, it seemed to me that the conference’s political consensus regrettably ended up paralysing discussions by nipping productive frictions in the bud.

Sticky questions around identity politics

The drawback of this political commitment is that critical analysis of movements’ advocacy strategies and their limitations increasingly lacks moral legitimation – especially from an outsider perspective. In my article “Racialised Land Rights as a Faustian bargain”, I operationalise racial capitalism theory and political settlement analysis. I point to the inherent limits of Afro-Colombian communities’ strategic mobilisation of their African past to defend their livelihoods against extractive capitalism and land grabbing. While the strategy has been successful in granting communities collective land rights, it has not resulted in addressing local material and financial demands. Being dependent on external financial aid, the communities’ leaders have found it difficult to address this paradox. The movement’s “strategic essentialism” means leaders struggle to address community members’ effective entanglement with the global economy as consumers, raw commodity producers and labourers.

Clearly, important gains have been made by these communities. However, how can we, as ‘foreign’ researchers, build solidarity with communities while also highlighting the distributional inequalities often associated with the gains made by these movements? Reflexivity and positionality are crucial in academic research. Yet, we must find ways to be allies with social movements while also avoiding romanticising the ‘universal’ or ‘mutual benefits’ that are promised by movements but not always delivered.

Ways forward?

Here is the question that emerges from these observations: How might academic research be self-reflexive, critical and supportive of social change all at once? Filipino activist Danny Carranza, from the NGO Rights Inc.-Katarungan regretted at the conference that the few researchers who do actively get in touch with social movements are too few to overcome neoliberal mainstream voices. While I do not think that academics should aim at becoming the mouth pieces or unconditional allies of social movements, I agree with the declaration at a final plenary that academics should aim at documenting struggles, debunking narratives and making sure that “people are not made complicit in their own dispossession”. Yet, to do so, we must investigate the economic structures that – good or bad – frame our globalised world. Even more importantly, we must be critical irrespective of political affiliations and cultural identity. In short, we all have to become better critical economists.

0 Comments