Assessment and AI

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is no longer a distant science fiction concept but an emerging reality shaping various aspects of our lives. Current AI models, including large language models (LLMs), are restricted by biases and a lack of profound understanding: however, imagine a world where AI can mimic high-quality student work effortlessly and at no cost. Far from mere speculation, this scenario appears closer and closer, and this calls us to redefine our approaches to learning, assessment, and education in general. A recent wicked problem panel at the UoM Teaching and Learning Conference 2023, led by Dr Cesare Ardito and Professor Rebecca Hodgson, brought together several academics to grapple with this complex issue.

The panel’s working assumptions set the stage: AI models with limitations but a foreseeable advancement to mimic student work; an AI capability that is broadly accessible and freely available; and a focus on the implications rather than the probability of such advancements. These assumptions, though hypothetical, helped the panel to focus on the exploration of complex educational dilemmas.

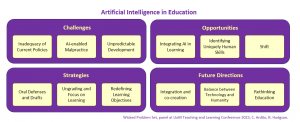

One of the most striking challenges identified was the unknown and unpredictable pace of development of AI technology. With the constant and rapid evolution, rushing into changes might be premature and even risky, as a new approach focused on the short-term might become obsolete tomorrow, presenting a paradox for educators and policymakers. An example: in many current university policies, it’s not uncommon to find stipulations requiring the disclosure of prompts when generative AI has been utilized in academic work. While this approach can currently be functional, it is inadequate to deal with more sophisticated and integrated forms of AI, such as the upcoming Microsoft Copilot.

Of course, among the most urgent challenges is the risk of AI-enabled academic malpractice or poor practice, making standard assessments less reliable. Many of the suggestions from the group echoed the guidance recently released by QAA.

First, the panel highlighted the necessity to protect students from the unreliability of AI detection and the consequences of false positives; then, it considered some strategies to counteract AI-assisted cheating, such as including more oral defenses and focus on drafts, assessing process as well as product. It was pointed out that students are often resort to cheating due to assessment design – high stakes single points of failure in terms of end of module assessments, rather than more iterative and integrated assessment over the course of study. Another idea was to consider “ungrading” as a means to shift the focus from assessment to the learning process, although more research as to the impact of removing grades is needed. One provocative idea – already being used by some academics – was to ask students to critique AI output as part of an assessment, encouraging them to co-create with it, fostering a partnership rather than competition and teaching them the correct use of the new tools.

The discussion then shifted to the more general necessity of rethinking assessment’s purpose in a world where even learning objectives should evolve to take into account the presence of generative AI. Participants found themselves pondering questions like “What are we assessing? Why are they learning? What is integrity?”, and there was a palpable excitement about the potential to identify and focus on what makes human intelligence unique. By focusing on human skills and motivations, AI might be harnessed to enhance, rather than replace, human creativity and critical thinking. Perhaps paradoxically, AI may also be able to support with more personalised learning and feedback approaches, offering some solutions to the challenges of giving students more one to one support and coaching, as well as marking and providing feedback at ‘scale’.

But these strategies brought forth another question: Why isn’t a machine like “Professor GPT” better than a human lecturer? It’s a provocative question that opens a wider dialogue about the human element in lecturing and the tangible essence of learning that goes beyond grades and competition.

The session’s conclusion left us with not just answers but more questions, challenges, and possibilities. In a world with increasingly advanced generative AI, the responsibility falls on us to redefine education and preserve the rich tapestry of human learning, nudging everyone to ponder the integrity of assessment, the motivation behind learning, and the vital balance between technological innovation and human essence.

It’s not just about integrating technology into the existing system, but about reimagining and reinventing the way we approach education. What is certainly essential is an upskilling of the educational workforce, in order to move beyond the idea of AI as ‘Google Plus’ and be able to both understand its application and utilise it fully. It’s a task that invites all educators, technologists, policymakers and learners to partake in with both enthusiasm and vigilance, for the future of education and human knowledge may well depend on how we respond to the tantalizing and perplexing promises of AI.

Further Reading:

- Cesare’s previous blog on AI

- The 2023 ITL Conference Minisite at which the paper was delivered.

0 Comments