Audio Feedback: Personal Reflections and Pedagogical Review

A recent arrival at Manchester, Peter O’Connor worked in the American Studies Department at the University of Nottingham before taking up the post of Lecturer in Modern American History in summer 2022. His research focuses on Anglo-American culture and politics in the long nineteenth century (1776-1914) He is also interested Higher Education pedagogy with a particular emphasis on skills acquisition and feedback practices.

A recent arrival at Manchester, Peter O’Connor worked in the American Studies Department at the University of Nottingham before taking up the post of Lecturer in Modern American History in summer 2022. His research focuses on Anglo-American culture and politics in the long nineteenth century (1776-1914) He is also interested Higher Education pedagogy with a particular emphasis on skills acquisition and feedback practices.

Anyone working in a teaching capacity within HE will have similar stories when it comes to the release of grades. While students eagerly anticipate finding out their marks, it can sometimes feel like students struggle to engage with the feedback we provide. This isn’t paranoia on our part. In their discussions of the existing literature on the topic, Price et al. and Lunt & Curran emphasize that learners often either fail to access or engage with the written feedback that is provided (Price et al, 2010; Lunt & Curran, 2010). The consequences are predictable. In terms of student achievement: a failure to engage with feedback limits the ability to feed forward and thereby improve performance. While not necessarily seeing the situation in the same light as teaching staff, the fact that feedback is one of the areas of consistent criticism for every institution within the NSS implies a recognition among students that current practices aren’t ideal.

Works by Price et al. and Duncan (Price, 2010; Duncan, 2007) highlight a lack of understanding among students about the meaning of feedback and low levels of ‘feedback literacy.’ Higher education as a whole might need to reflect more on how we develop better feedback literacy within the student body since the gap appears to be nationwide and have no correlation with the way we deliver teaching. From my personal experience, however, the mode of feedback we provide may help to facilitate engagement even if larger changes are needed to overhaul the process.

https://www.qmul.ac.uk/queenmaryacademy/educators/resources/assessment-and-feedback/resources/assessment-and-feedback-literacy/

I was led by circumstance to experiment with audio feedback as a lecturer at the University of Nottingham in winter 2020, and was pleasantly surprised to find improved levels of engagement among students when it came to my comments. More so than in the past, they contacted me asking for clarification or to discuss how they could apply what I was suggesting in different contexts. They also explicitly commented that they felt they got more out of my feedback when it was delivered in this form.

Looking into pedagogical work on the topic it became clear that my experience in this regard was typical. Both within reviews of the existing literature and via their own research, with research finding high levels of student positivity in relation to audio feedback (Rasi & Vuojarvi, 2018; Carruthers et al., 2015; McKeown et al. 2015). In many cases, the reasons for this positivity echoed what I had heard from own students. They found comments easier to understand. They often associated this with the ability to pick up on subtleties in pacing and tone of voice (Merry & Orsmond, 2008; Lunt & Curran, 2010; Killingback, Ahmed & Williams, 2019; Hennessey & Forrester, 2014). Research suggesting that students felt they got a greater insight into the marking process and found positive reactions from students to audio feedback in relation to convenience, flexibility and personalization, also mirrored my own experience; learners believed they got a better sense of how the marking criteria was applied through my audio comments). (Carruthers, 2015, Parkes & Fletcher, 2014).

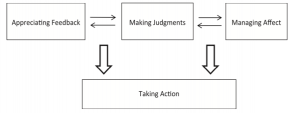

While the nature of these positive comments was what I would have predicted based on my own experience, the nebulous concept of personalization (which Carruthers highlights) raised an issue that I had missed. Despite being quite difficult to quantify, scholarship on the topic of audio feedback suggests a strong connection with emotional impact and community building. Rasi & Vuojarvi foreground both the importance of emotional engagement for learning and the fact that a student’s emotional state is frequently tied to the feedback they receive (Rasi & Vuojarvi, 2018).. Receiving comments in this form makes students feel cared for (Lunt & Curran, 2010).

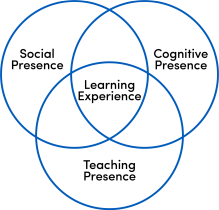

This sense of emotional investment also facilities the emergence of a community of learning by establishing a relational engagement between student and teacher (Price et al. 2010). In all of the literature which I have reviewed, ideas of developing a personal connection, having a social presence or creating a sense of approachability are highlighted as by-products of audio feedback (Hennessey & Forrester, 2014; Parkes & Fletcher 2014; Gould & Day, 2013; Ice et al. 2007). This connection can be fostered even without face to face contact with the lecturer, and contributes to a broader sense of pastoral care (Rasi & Vuojarvi, 2018; Killingback et al. 2019). In this way, audio feedback may have been a vital aspect of the community for my students during lockdown and even now it can help to create an environment which encourages disengaged students to return to the classroom.

https://www.buffalo.edu/catt/develop/teach/learning-environments/community-of-inquiry.html

The final point to make here is practical. As staff struggle with high workloads, does changing the delivery mode for feedback create a new burden? Speaking from a personal perspective, I would say no. Since I started teaching in HE a decade ago I’ve marked the extended written pieces which are the historian’s stock ion trade in the same way. I offer in-text annotations on the turnitin script along with a set of overall reflections in the free text box on the right of the screen. When providing written feedback, I go back and work these comments into something coherent. As someone much more comfortable with verbal communication, I found it a time saver to use these draft comments as the basis for an audio recording before deleting them.

One of the key takeaways from both my personal experience and subsequent research is that audio feedback allows me to fulfil my aims as a teacher. Yet it’s important that while staff who want to utilize this approach are given the opportunity to do so, it should not be centrally mandated. What saves time for some may not save it for others. Furthermore, many of the advantages of audio feedback vis-a-vis community building are predicated on ideas of personalization and enthusiasm. To mandate audio feedback to those who do not believe it serves a purpose would seem highly likely to undermine the very reasons for its adoption.

References

- Carruthers, C., McCarron, B., Bolan, P., Devine, A., McMahon-Beattie, U., Burns, A., 2015 ‘”I Like the Sound of that”- An Evaluation of Providing Audio Feedback via the Virtual Learning Environment for Summative Assessment’ Assessment & Learning in Higher Education 40 (3), 352-370.

- Gould, J., Day, P., 2013 ‘Hearing You Loud and Clear: Student Perspectives of Audio Feedback in Higher Education’ Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 38 (5) 554-566.

- Hennessey, C., Forrester, G., 2014 ‘Developing a Framework for Effective Audio Feedback: A Case Study’ Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 39 (7) 777-789.

- Ice, P., Curtis, R., Phillips, P., Well, J., 2007 ‘Using Asynchronous Feedback to Enhance Teaching Presence and Student’s Sense of Community’ Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks 11 (2) 3-25.

- Killingback, C., Ahmed, O., Williams, J., 2019 ‘”It Was All in Your Voice”- Tertiary Student Perceptions of Alternative Feedback Modes (audio, video, podcast and screencast): A Qualitative Literature Review’ Nurse Education Today 72 32-39.

- Lunt, T., Curran, J., ‘”Are You Listening Please?” The Advantages of Electronic Audio Feedback Compared to Written Feedback’ Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 45 (7) 759-769.

- McKeown, D., Kimball, K., Ledford, J., 2015 ‘Effects of Asynchronous Audio Feedback on the Story Revision Practices of Students with Emotional/Behavioural Disorders’ Education and Treatment of Children 38 (3) 541-564.

- Merry, S., Orsmond, P., 2008 ‘Students’ Attitudes to and Usage of Academic Feedback Provided by Audio File’ Bioscience Education Journal 11 (1) 1-11.

- Parkes, M., Fletcher, P.R., 2014 ‘Talking the Talk: Audio Feedback as a Tool for Student Assessment’ in Viteli, J., Leikomaa M., eds., Proceedings of the World Conference on Educational Media and Technology (Chesapeake: Association for the Advancement of Computing in Education) 1606-1615.

- Price, M., Handley, K., Millar, J., O’Donovan, B., 2010 ‘Feedback: All that Effort, But What Is the Effect?’ Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 35 (3) 277-289

- Rasi, P., Vuojarvi, H., 2018 ‘Toward Personal and Emotional Connectivity in Mobile Higher Education Through Asynchronous Audio Feedback’ British Journal of Educational Technology 49 (2), 292-304.

0 Comments