Building Science Belonging: Using Foldscope Outreach to Enrich Primary Teaching and Learning

Samina Naseeb is teaching-focused lecturer passionate about making science more accessible to children who may not see themselves as ‘science people’. She recently led a Microscopy Foldscope outreach project in less privileged primary schools and schools with higher numbers of Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic (BAME) pupils across Greater Manchester. The project was funded by the University’s Access and Widening Participation team and aligns with institutional goals to address persistent gaps in progression to higher education among pupils from low-income and underrepresented backgrounds. This piece shares her reflections on the practicalities, insights, and lessons learned from engaging young pupils with science in ways that help build confidence and curiosity.

Samina Naseeb is teaching-focused lecturer passionate about making science more accessible to children who may not see themselves as ‘science people’. She recently led a Microscopy Foldscope outreach project in less privileged primary schools and schools with higher numbers of Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic (BAME) pupils across Greater Manchester. The project was funded by the University’s Access and Widening Participation team and aligns with institutional goals to address persistent gaps in progression to higher education among pupils from low-income and underrepresented backgrounds. This piece shares her reflections on the practicalities, insights, and lessons learned from engaging young pupils with science in ways that help build confidence and curiosity.

Why Building Science Belonging Matters

Widening participation remains a priority for UK higher education. Research shows that children begin forming ideas about who ‘belongs’ in science by age 10, and without early, meaningful intervention, these ideas can become deeply rooted. Many enjoy science but don’t see themselves as the kind of person who does science.

Science capital, which refers to the knowledge, experiences and connections that shape how young people relate to science, plays a key role in whether they continue with it beyond age 16. Yet access remains unequal, with persistent gaps linked to gender, ethnicity and socio-economic background. Children in more deprived areas often lack exposure to STEM activities and role models.

Early-stage outreach helps build both science capital and campus capital – a sense that university is a place for people like them and connects classroom science to real futures.

What We Did: Taking Microscopes into Classrooms

Our Foldscope workshops aimed to break down that distance and were designed to be simple, practical and fun. The use of low-cost paper microscope offered a unique opportunity to bring practical microscopy – often inaccessible in under-resourced settings – directly into classrooms.

The outreach intervention involved designing and delivering a se

ries of 60-minute workshops for Key Stage 2 pupils:

- We started by a short introduction to scientists delivering the workshops and what studying science can look like, helping the pupils to connect the activity to higher education pathways.

- They then got hands-on, assembling their Foldscopes and examining everyday materials like leaves, pond water and fabric fibres.

- Some examples of activities included visualising strands of hair under the microscope, observing crystals using sugar and salt, and collecting feathers to observe their structure.

- Pupils were encouraged to make their own slides, ask questions about what they saw, and think about how they might test ideas – just like how real scientists do.

- This was followed by structured group discussions to help pupils develop scientific enquiry skills such as observing, predicting, and explaining.

Having a team of undergraduate, postgraduate students as well as postdoctoral research scientists deliver made the workshops feel real and relatable. Pupils were able to ask them not just about the science they were doing on the day, but also what it’s like to study and work as a scientist at different stages.

This face-to-face interaction helped demystify the pathway – showing that being a scientist isn’t a fixed identity, but a journey that people from all backgrounds can take. Importantly, the workshops were designed to be inclusive and to meet the diverse learning needs of young children, ensuring every child could actively participate and benefit.

Teacher and Student Quotes

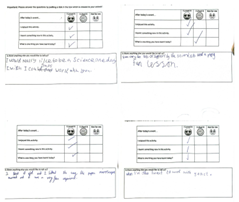

Teachers told us that many of their pupils had never used a microscope before. One teacher shared, “The children thoroughly enjoyed learning about microscopes. The adults leading the session were very knowledgeable and enthusiastic, it was so lovely to see our pupils excited about science..” pupils said the sessions gave them new confidence to ask questions and think like scientists.

This kind of practical, age-appropriate activity is one way to help build ‘science capital’. This work strengthened the loop between outreach and teaching practice by providing real-world examples that can be used to engage undergraduate students in discussions of science communication, equity, and civic responsibility.

What I Learned: Feeding Back to My Own Teaching

When I started this project, I was keen to help pupils see that science is for everyone and not just for people in lab coats. I wanted to demystify science and make it fun, especially for pupils who might not have much science capital at home. What I did not realise at first was how much this work would also feed back into my own teaching practice. Sharing stories from our Foldscope workshops helps my undergraduate and postgraduate students see science communication, inclusion, and public engagement as part of their own professional roles. More of my students are now choosing final-year research projects linked to outreach, inclusion or science communication. My hope is that by making practical science accessible, relevant and fun, we help pupils see scientists not as distant experts, but as people they can aspire to become. If even a few carry that confidence forward, then this work will have made a meaningful difference. My hope is that we continue to build these bridges – not just between university and schools, but between people and possibilities.

References

Archer, L., Dawson, E., DeWitt, J., Seakins, A., & Wong, B. (2015). ‘Science capital’: A conceptual, methodological, and empirical argument for extending Bourdieusian notions of capital beyond the arts. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 52(7), 922–948.

Archer, L; Moote, J; Macleod, E; Francis, B; DeWitt, J; (2020) ASPIRES 2: Young people’s science and career aspirations, age 10–19. UCL Institute of Education: London, UK

Moote, J., Archer, L., DeWitt, J., & MacLeod, E. (2021). Who has high science capital? An exploration of emerging patterns of science capital among students aged 17/18 in England. Research Papers in Education, 36(4), 402–422.

0 Comments